Special 120th anniversary series: The A-bombing and the Chugoku Shimbun (Part 7)

May 18, 2012

Return to downtown offices

by Masami Nishimoto, Senior Staff Writer

Determination to rebuild conveyed in paper’s pages

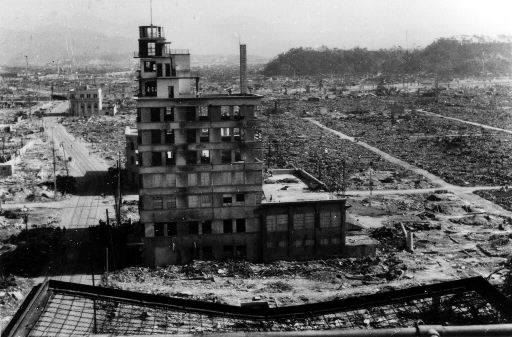

After the offices of the Chugoku Shimbun were destroyed by fire in the atomic bombing of August 6, 1945, the paper was printed by other newspaper companies until September 3. Then printing resumed in Nukushina (now part of Higashi Ward) on the outskirts of Hiroshima, where a rotary printing press had been taken. But on September 17, not long after the Chugoku Shimbun began issuing reports from A-bombed Hiroshima, publication was halted again by the Makurazaki Typhoon. With that, a decision was made to return to the paper’s burned-out offices in Kami-nagarekawa-cho (now Ebisu-cho, Naka Ward). Despite another disaster, the newspaper’s employees persevered.

Employees pull together: A new start amid the ruins

In the 1967 “A-bomb Mayor,” Shinso Hamai, Hiroshima’s first publicly elected mayor who devoted himself to the rebuilding of the city, described the Makurazaki Typhoon as a “tragedy on the heels of tragedy.” At the time of the A-bombing Mr. Hamai was 40 and employed as the city’s ration system section chief.

“From the roof of the City Hall I saw what appeared to be a large lake,” he wrote. “Rubble and collapsed houses vanished under the untroubled surface… In one night, the ‘atomic desert’ had changed to an ‘atomic lake.’”

Press inundated by typhoon

On September 17 195.5 mm of rain fell, and in the pre-dawn hours of September 18 record gusts of 45.3 meters per second were recorded. A total of 2,012 people died in Hiroshima Prefecture, particularly in Kure and Ono-cho (now part of Hatsukaichi), where mudslides occurred. Why was it such a catastrophic disaster?

Mountain areas had been laid waste by the building of roads for military use and air raid shelters. And, according to a record of damage from landslides in Hiroshima Prefecture published in 1997, “Because of the damage from the atomic bombing, the telephone lines to the meteorological observatory had not been restored… There was no system for conveying information to the public via radio.” The Hiroshima Central Broadcasting studio, which had relocated to Gion-cho (now part of Asa Minami Ward) was flooded in the pre-dawn hours of September 17, according to a history published by NHK in 1988 for the 60th anniversary of the Hiroshima bureau.

Multiple factors combined to magnify the damage. Printing at the Chugoku Shimbun’s plant in Nukushina ceased after publication of the September 18 edition when the Nukushina River (now the Fuchu Okawa River), which ran alongside the plant, flooded.

Chief Editor Tetsuo Murakami, then 40, went to Tokyo and described the scene for the October 13 edition of the news bulletin of the Japan Newspaper Publishers & Editors Association under a headline that read, “Wind and flood damage completely destroy relocated plant.” The article also noted that urgent efforts to restore the newspaper’s downtown office building were underway.

“The rotary press’s motor was flooded, mud got into it and the printing paper was completely ruined,” Mr. Murakami said. “The employees and their families who have been staying at a nearby temple or living in tents have become disaster victims once again. The paper is being printed with the assistance of the Mainichi and Asahi newspapers.”

Jitsuichi Yamamoto, then 55 and president of the Chugoku Shimbun, debated whether the company should return to its offices amid the ruins or remain in Nukushina. He reportedly made his decision after exhaustive discussions with his son Akira, then 26 and recently discharged from the military, Mr. Murakami and other middle managers.

Akira Yamamoto became chairman of the paper in 1992. From that year through the following year he participated in a project conducted by the Japan Newspaper Publishers and Editors Association to compile a history of Japan’s newspapers through interviews. Mr. Yamamoto’s recollections were included in a separate volume of the association’s bulletin published in August 1995.

Mr. Yamamoto consulted with Masao Tsuzuki, a professor at Tokyo Imperial University, who had formed a joint Japan-U.S. survey team that had come to Hiroshima and had returned to the city in October. “He said we could go back to our offices once we had a test done to determine whether or not there was residual radiation from the atomic bombing.” The Hiroshima University of Literature and Science also said returning to the paper’s offices would be no problem. The cleaning and renovation of the company’s offices began with the assistance of the Chugoku Recovery Foundation.

After living in a tent at the site of the Nukushina plant, Hidefumi Sumida, 83, who later designed the paper’s visual elements, took up temporary residence in the company’s Chugoku Building downtown.

“We boarded up the windows to keep wind and rain out. I stayed in the same room with my mother [an employee of the advertising department],” he said. “People came from the newspaper’s bureaus to help out, and others brought their families with them. There must have been about 30 of us.”

Yasuo Yamamoto, then 42, was told to serve as leader of the reconstruction work team for the downtown offices. “We raked the soil behind the building, which had human bones mixed in it, and then started growing vegetables there,” he wrote in the August 1965 edition of “Shinju,” a poetry anthology he edited.

When the paper began to be printed by other newspaper companies again, Ichiro Osako, then 32, and other news reporters put out a mimeographed paper they called “The Chugoku Shimbun News Flash.” It carried reports based on information they had gathered from the Hiroshima bureau of the Domei News Agency and the prefectural government offices, which had been relocated to the premises of Toyo Kogyo (now Mazda). Employees of the newspaper and the prefecture distributed the papers, posting some of them at railway stations.

Mr. Osako recalled his disconsolate feelings while there was no paper in “Hiroshima 1945,” a series of articles addressing the newspaper’s responsibility for the war that were published in the evening edition of the Chugoku Shimbun in 1975. He got into an argument over drinks with a prefectural employee who had just been discharged from the military.

“The newspaper kept telling people we’d win the war… We don’t need a paper like yours that cozied up to the military,” the prefectural employee said.

“What are you talking about?” Mr. Osako said. “It’s the government that nearly killed us off.” After he returned home he repeatedly said to his wife, “I want a newspaper; I want space in the paper. There are so many things I want to write about.”

Tearfully recalling dead colleagues

Amid the continuing chaos, some new employees came to work for the company.

Jihei Yoshida, 89, visited the Chugoku Shimbun offices amid the ruins on September 1 just after being discharged from the military in Kyushu. His mother and three younger sisters had died in the atomic bombing. His father, who had died of illness prior to the war, had been a reporter for the Chugoku Shimbun.

“I felt the power of the pen was necessary to build a democratic nation and to rebuild Hiroshima,” he said. “There was no doubt in my mind that I was going to work for a newspaper company,” Mr. Yoshida said. As a business reporter for the paper he traveled to rural areas of the prefecture that had been hit by the typhoon and reported on the damage. He still has his business card from those days.

Reiichi Hashimoto died on October 20, 1945 after being exposed to the atomic bombing while on his way to work. He was 49 and worked as assistant manager of the paper’s typesetting department. His son, Jun Hashimoto, 84, recalled, “My mother and I went to the newspaper offices, which were merely a shell, to tell them my father had died. Jitsuichi [Yamamoto, company president] invited me to come to work for the paper.” Mr. Hashimoto brought burned power poles to the newspaper’s offices and burned them for heat and dedicated himself to newspaper sales.

The press at the Nukushina plant, which had been vital to the company’s rebuilding, was disassembled and brought back to the city.

In a special volume published by the Japan Newspaper Publishers and Editors Association Akira Yamamoto recalled, “We loaded it onto a horse cart and brought it back in several loads until we finally had all of it at the downtown offices… We asked people from Toyo Kogyo to put it together for us.”

The surviving employees and others who hoped the Chugoku Shimbun would play a role in the rebuilding of the city worked together to return to publishing from the downtown offices. The paper resumed publication at its downtown offices amid the ruins on November 5, one day before the three-month anniversary of the A-bombing.

Akira Yamamoto, who led the return to the downtown offices, recalled the “night of the 4th” in his memoirs, which he wrote throughout his later years. (Mr. Yamamoto died in 1998 at the age of 78.)

“As dawn approached and it began to grow light, the sound of the press’s smooth rhythm finally began to be heard. I stood beside the press and, while listening to its roar, wept as I recalled the faces of all of those who had died.”

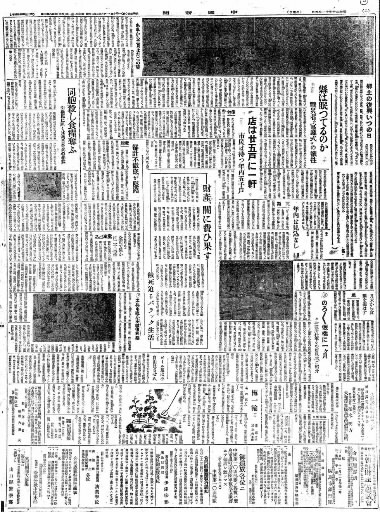

Under a headline saying, “When will hometown recover?” the top of page 2 of the paper’s November 5 edition featured an article describing the status of housing, electric lighting and gas as well as streetcar and bus service.

“Rather than some elaborate, grand, esoteric concept of recovery, what citizens long for is no more or less than homes that will protect them from the cold, clothing, and supplies of food to stave off hunger.” Rubble covered the devastation, and, according to a November survey by the city, the population had been fallen to just over 136,000, less than one third what it had been before the A-bombing.

The sound of the hammers of rebuilding grew following the promulgation of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Law, special legislation passed by the central government in 1949. The population of the city returned to its pre-war level of 400,000 in 1957. Rebuilding of the Chugoku Shimbun continued to be an arduous task. After a growing ban-the-bomb movement followed by a split within its ranks, news coverage that took a hard look at the effects of the atomic bombing and viewed nuclear weapons from a human standpoint began in earnest with a series of articles “20 years after the Bombing” published in conjunction with the 20th anniversary of the bombing, which received the 1965 Japan Newspaper Publishers and Editors Association Prize.

Passing “indomitable spirit” on

The 1.2 million people of today’s Hiroshima and the Chugoku Shimbun owe their existence to the indomitability of our predecessors in the face of unprecedented hardships.

Shinichi Kato (died in 1982, aged 81), one of the first to arrive at the burning newspaper’s offices, used his English skills to become a pioneer in an international citizens’ movement. Yasuo Yamamoto (died in 1983, aged 80) was a pillar of Hiroshima’s poetry movement. Shigetoshi Itokawa (died in 1983, aged 78), who used the military’s radio network to ask other newspaper companies to print the Chugoku Shimbun, led the Hiroshima Society for the Research of Atomic Bomb Sufferers.

Ichiro Osako (died in 1995, aged 83) also authored “Dr. Junod: Hero without Weapons” and, along with Yoshito Matsushige (died in 2005, aged 92) who photographed the devastation just after the atomic bombing and others, published “Hiroshima: A Special Report” in 1980. In this publication they filled in the blanks and described what had happened during the two days after the bombing during which the paper was not published.

Today, May 5, marks the 120th anniversary of the founding of the Chugoku Shimbun. Jiro Yamamoto, 63, the company’s chairman, said, “I believe that that indomitable spirit is in the DNA of not only the newspaper but also the city of Hiroshima. Those of us to whom this spirit has been passed on must not allow it to die and must work to pass it on to future generations.”

“With communications cut off and the rotary press not operable, how could the paper carry out its mission?” A special resolution adopted at last year’s National Newspaper Convention described maintaining daily publication in the disaster area during and in the wake of the earthquake and tsunami last March 11 as the “basis of newspapers.” “We will continue to meet the obligations of newspapers as a public institution,” the resolution said.

This is also the basis of the Chugoku Shimbun, which has its headquarters in Hiroshima, the victim of an A-bombing. The paper’s determination to pass on the “indomitable spirit” of its predecessors and go forward hand in hand with its readers and the local community remains unchanged. (This is the last article in this series.)

(Originally published on May 5, 2012)