Vietnam: 50 years after the use of defoliants

Jul. 3, 2012

3 million still suffering effects of dioxin

by Takamasa Kyoren, Staff Writer

U.S. military “weapon”

After its intervention in the Vietnam War, the U.S. military used defoliants containing poisonous dioxin in order to achieve a breakthrough in the conflict. From 1961 through 1971 a total of 80 million liters of defoliant were sprayed over South Vietnam. There are believed to be 3 million Vietnamese victims of the effects of defoliants, who have suffered illness and handicaps as a result. In this article the Chugoku Shimbun explores the background behind the war and the spraying of defoliants and the facts regarding their lingering effects. This story also features interviews with three experts from Japan and Vietnam who are involved in efforts to provide support for victims.

80 million liters sprayed

Many babies born with abnormalities

Ngo Ngoc Tot, 82, lives in My Tho, a town in the Mekong Delta at the southernmost tip of Vietnam. As a leader in the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (Viet Cong) during the early 1960s, Mr. Ngo participated in fighting in the thick jungles around My Tho. One morning he spotted three aircraft flying overhead while spraying something resembling white mist.

A few days later the leaves of the trees turned yellow, died and fell off. But the jungle was the people’s only source of food, so they ate bananas and drank water that had been contaminated by defoliants.

More than 50 years have passed since then. Mr. Ngo’s elder daughter, Ngo Ngoc Hanh, 48, suffers from atrophied muscles and a brain disorder. His younger daughter, Ngo Ngoc My, 46, has mild brain damage. His four sons, who were born before the war, are healthy. Mr. Ngo, who suffers from heart disease, blames himself for his daughters’ suffering. “By going off to war, I destroyed my daughter’s lives,” he said. He and his daughters have been certified as defoliant sufferers and live on government assistance.

◇

During the war, the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese army hid out in the jungles of South Vietnam and launched attacks from there. The U.S. military decided to use defoliants in order to hit the enemy’s bases. Another of their goals was to destroy fields in villages where residents were secretly cooperating with the north and cut off their supply of food. The U.S. declared to both its enemies and its allies that defoliants were not harmful to people or animals.

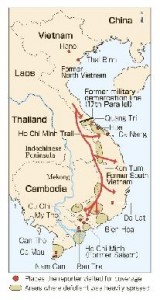

A trial spraying of defoliant was conducted in August 1961 in Kon Tum Province in central Vietnam. Spraying was carried out about 20,000 times through October 1971, and a total of about 80 million liters of defoliant was used in various regions. The South Vietnamese military is believed to have continued the spraying after that.

Spraying was particularly heavy in the vicinity of the Ho Chi Minh Trail, the northern supply route which ran through the mountains along the border with Laos, and in the Mekong Delta, which was a base of operations for the Viet Cong. Defoliant was also sprayed over neighboring Laos and Cambodia, but precise figures have yet to be made public.

Since the war, there has been a high incidence of babies born with abnormalities and cancer patients in the area in which defoliant was sprayed. Dr. Nguyen Thi Ngoc Phuong, 68, former director of Tu Du Hospital in Ho Chi Minh City, the largest obstetrics hospital in Vietnam, was a trainee doctor in the early 1960s. She was surprised at how many babies at the hospital were born with abnormalities. She and a coworker researched the hometowns of the babies’ parents and the rate of abnormal births prior to the war. They also sent stillborn fetuses to research institutions overseas. As a result, they found that the number of abnormal births had increased rapidly throughout South Vietnam from 1962 to 1965, and the greater the amount of defoliant that had been sprayed, the higher the rate of abnormalities.

In 1982 Dr. Nguyen conducted a survey of 1,000 households in Ben Tre Province and Ho Chi Minh City on the rate of miscarriages and premature births. In instances in which a parent had been exposed to defoliants, the rate was between 8.01 and 16.7 percent. Where there had been no exposure to defoliants, the rate was 3.6 percent.

Meanwhile the government of Vietnam has yet to conduct a nationwide survey on the number of victims of defoliants and the rate of congenital disorders.

◇

According to research by Jeanne Mager Stellman, 65, a professor at Columbia University in New York, a total of 366 kg of dioxin was dispersed in defoliants. The World Health Organization has stated that a person weighing 60 kg can be exposed to up to 240 picograms of dioxin a day without experiencing any ill effects. (One picogram equals one trillionth of a gram.) A total of 4.8 million people live in the area in which defoliants were sprayed. Of these, 3 million are said to have experienced health problems. The land and the rivers also show traces of pollution.

In 2004 representatives of the Vietnam Association for Victims of Agent Orange/Dioxin (VAVA) filed a suit for damages against the U.S. chemical companies that manufactured the defoliants, but in 2009 the U.S. Supreme Court threw out the lawsuit stating, “Defoliation was not in violation of international law nor has a causal relationship been shown between defoliants and the harm suffered by the Vietnamese people.”

In contrast, in 1984 U.S. chemical companies paid $180 million to settle a similar class-action lawsuit filed against them by military personnel who had served in Vietnam.

In 1991 the U.S. government began paying compensation for defoliants to some military personnel who served in Vietnam, but since the normalization of diplomatic relations in 1995 the U.S. has refused to acknowledge responsibility for the effects suffered by the Vietnamese and has paid no compensation to them.

According to VAVA, in 2011 the Vietnamese government provided approximately $70 million to be used for support for victims. Some former military personnel and their children receive a monthly benefit of between $20 and $90 per month, but no payments are made to civilians.

Environmental measures have finally begun to be taken. A project to remove dioxin at Da Nang International Airport in central Vietnam was launched in 2011 in a joint effort between Vietnam and the U.S. The airport is one of 28 hot spots in Vietnam where high levels of dioxin remain. It is expected to take at least 20 to 30 years to decontaminate all 28 hot spots.

Defoliants

Defoliants are herbicides containing highly toxic dioxin, which were used by the U.S. military in the Vietnam War. They were manufactured by Dow Chemical, Monsanto and other U.S. chemical companies.

There were 15 types of defoliants, distinguished by the color of the drums in which they were stored: white, purple, blue, etc. Each was used against certain types of foliage, trees or crops. Agent Orange, which represented about 60 percent of the total amount of defoliants used, is particularly toxic. For that reason, organizations that provide support to victims and other groups use the color orange in their logos.

At the time of the Vietnam War, the use of chemical weapons was prohibited internationally by the 1925 Geneva Protocol, but the protocol did not state whether or not defoliants should be defined as chemical weapons. The U.S. declared that defoliants were not harmful to people and continued to use them, saying that they were not weapons. The U.S. ratified the Geneva Protocol in 1975. The preamble to the 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention includes a prohibition on the use of defoliants in war.

An interview with Goro Nakamura, 71, news photographer

Like experimenting on living animals

At the time of the Vietnam War, coverage led to a wave of protest against the war around the world. On the other hand, few people know about the suffering of the Vietnamese people since the war. Those of us who live in Asia must not overlook the fact that in the shadow of Vietnam’s economic growth there are victims of the war who can not speak out.

In 1974 I covered the war in North Vietnam for a news agency. I wondered what Vietnam was like after liberation, so in 1976 I went to Ca Mau in the Mekong Delta, the southernmost province in Vietnam. The mangrove forests, which should have been lush with foliage, were dead as far as the eye could see. No birds could be heard singing, and it was strangely quiet. A local midwife said there had been many conjoined twins and babies born with other abnormalities. I had a feeling that something similar to the suffering experienced by the survivors after the atomic bombing in Hiroshima was beginning, and I began covering the situation.

As with the A-bombing, the reality of the tragedy gradually became clear after the war. Now, more than 30 years later, the fact that I must continue my reporting is a testimony to the horrors of defoliants.

During the war U.S. researchers warned of the toxicity of dioxin. But the U.S. military sprayed it in areas where people lived and where crops were grown. Even now there are people who must live in contaminated areas. It’s like experimenting on living animals. The state pushed forward with its immediate goals and then afterwards ignored the harm that had been done. We must continue to lend support to the victims.

Goro Nakamura

Born in 1940 in Beijing. After working for a news service, became a freelance photographer in 1981. Has pursued the issues of defoliant and pollution in Japan. Has photos on permanent display in the War Remnants Museum in Ho Chi Minh City. Author of “Defoliants on the Battlefield,” “My Mother Was Sprayed with Defoliant” and others. Resident of the city of Saitama near Tokyo.

An interview with Susumu Iwamoto, 69, chairman of Yudaen, Yamaguchi Prefectural social welfare center for A-bomb survivors

As with atomic bombings

Facts must be cleared up

While I was studying in the United States from 1969 to 1972, friends at college said things to me like, “My father was killed in Vietnam the other day” or “My wounded brother has come home.” The war was right there. That was the start of my ongoing involvement with the Vietnam War.

Around 2000 at a symposium in the city of Yamaguchi, I learned about the residual dioxin in Vietnam. I was shocked. My brother and other doctors and I launched a survey in the vicinity of Da Nang International Airport. People asked, “Why are you studying defoliants now?” But even then we detected high levels of dioxin in the soil around there and in the blood of elementary and junior high school students. I was convinced that a problem still existed.

The children who gathered in the school auditorium to have blood samples taken did not know why they had been called there. There had been a warning that well water and fish from certain areas were harmful, but the facts had not been conveyed to local residents. We gave a presentation at an international conference in Hanoi and submitted a report to the Japanese government, from which we received a subsidy, but I wonder how useful that was.

Both the atomic bomb and defoliants have caused many people to suffer for a long time. I have had contact with atomic bomb survivors over the years. The people of Hiroshima and the Vietnamese people fervently desire peace. The call for peace by the atomic bomb survivors reached the people of the world and has prevented the use of atomic bombs since the bombing of Nagasaki. In order to ensure that the tragedy of Vietnam is not repeated, we must continue to pursue the facts surrounding the harm that resulted.

Susumu Iwamoto

Born in 1943 in the former Manchukuo (now northeast China). While a professor in the Nursing Department of Yamaguchi Prefectural University from 1999 to 2001, conducted a joint study with Hanoi Medical University in Da Nang, Vietnam, on the effects of defoliants. Provides assistance to victims through a non-governmental organization for which he serves as president. Resident of the city of Yamaguchi.

An interview with Nguyen Minh Y, 71, director of the External Relations Department, the Vietnam Association for Victims of Agent Orange/Dioxin (VAVA)

International support essential

In Vietnam it was commonly believed that the birth of children with congenital disorders was retribution for wrongdoing by the child’s ancestors. No one knew anything about dioxin, so the victims and their families could only hide their suffering while experiencing prejudice and discrimination.

VAVA was established in 2003 with the approval of the Vietnamese government. We provide rehabilitation and day care services as well as occupational training to the victims. We build new houses for poor families and have proposed the creation of new support measures to the government.

The effects of dioxin on health and its genetic influence have now been demonstrated by many scientists. In 2004 representatives of VAVA filed a suit for damages in the U.S. against the chemical companies that manufactured the defoliants. The lawsuit was the result of the pent-up anger of millions of victims who had been ignored for decades. But the suit was thrown out by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2009. The companies said that they merely manufactured the defoliants after receiving orders for them from the U.S. government and refused to accept responsibility. It was frustrating.

It is necessary to continue to pursue the liability of the U.S. government and the chemical companies. At the same time, there is an urgent need to provide support to the victims. There is a lack of funds. The majority of VAVA’s funds come from donations, and most of our staff members work without compensation. We will seek further international cooperation from the U.S., Japan and other nations.

Nguyen Minh Y

Born in 1940. After retiring from the Vietnamese Army served as director of the international bureau of a veterans association before assuming his current post. Resident of Hanoi.

Vietnam War

4 million civilian deaths

The Vietnam War, which took place from 1960 to 1975, was fought between North Vietnam and the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (Viet Cong) on one side and the U.S. and South Vietnam on the other. Behind the conflict lay a power struggle between the world’s superpowers in the aftermath of World War II.

With the 1945 surrender of Japan, which had occupied French Indochina, the Viet Minh, led by Ho Chi Minh, proclaimed the independent Democratic Republic of Vietnam in Hanoi. This led to the First Indochina War between Vietnam and France, which hoped to restore its rule over the country.

With the 1954 Geneva Accords, the French military pulled out of Vietnam and the country was divided into North Vietnam and South Vietnam at the 17th Parallel.

In 1955 a pro-U.S. administration was established in South Vietnam. It failed to conduct an election on the unification of north and south as had been stipulated in the cease-fire agreement in 1956. In 1960 North Vietnam decided to launch an armed conflict against the south in order to unify the Vietnamese people, and the Viet Cong was formed. This marked the start of the Vietnam War.

The U.S. regarded this as a “Communist invasion” and provided military support to South Vietnam. It also launched a full-scale military intervention with the bombing of North Vietnam and other tactics. By the end of 1969 the number of U.S. military personnel stationed in Vietnam had reached 540,000, including those dispatched from South Korea and the Philippines. With support from the Soviet Union and China, the north resisted, and the war bogged down.

The U.S. military used napalm bombs and various other new weapons, but it faced an uphill battle. The use of defoliants and the slaughter of civilians by U.S. troops were reported in the news, and the anti-war movement spread throughout the world. Hostilities were suspended with the signing of the Paris Peace Accords in 1973, and U.S. forces begin pulling out of Vietnam. In April 1975 Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City) fell to the North Vietnamese Army, and the war came to an end.

A total of about 1.3 million military personnel were killed in North and South Vietnam, and another 4 million civilians, including members of the Viet Cong, died. About 58,000 U.S. military personnel were killed.

Rapid growth with introduction of market economy

Economic reforms of 1986 Doi Moi

The official name of Vietnam is the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, and since its founding in 1976 the country has been ruled by the Communist Party under a single-party regime. The population of Vietnam is approximately 87 million, and it has 54 distinct ethnic groups. With an area of approximately 330,000 square kilometers, Vietnam is slightly smaller than Japan.

Under the Doi Moi economic reforms, which were adopted in 1986, a market economy was introduced, and the country began to grow rapidly following the entry of foreign companies in the early 1990s. Since 2000 the economy has grown at an annual rate of between 5 and 9 percent.

In recent years large foreign supermarkets and convenience stores have opened one after another in the capital of Hanoi and in Ho Chi Minh City, the largest city in the country. These coexist with markets where fish and vegetables are sold and peddlers who travel about with poles on their shoulders. Japanese cosmetics and manga are popular with young people.

The average monthly salary of employees of state-run enterprises and government agencies and organizations is about $160. Many people have side jobs. In the hot, rainy season temperatures may exceed 40 degrees Centigrade. The Vietnamese customarily take a nap in the afternoon, and people can be seen here and there lying on benches or straw mats.

There are many ethnic minorities in the area along the border with China, in the central mountains, and in the Mekong Delta in the south. In many of these areas education and medical care is inadequate.

The Vietnam War and the Use of Defoliants

1925 Geneva Protocol prohibits use of chemical weapons in war

1940 Japanese Imperial Army occupies northern French Indochina

1945 Japan surrenders unconditionally as World War II ends; Democratic Republic of Vietnam proclaimed

1946 First Indochina War between Vietnam and France begins

1954 Vietnam divided into North and South Vietnam by the Geneva Accords

1955 Republic of Vietnam established in South Vietnam; pro-U.S. Ngo Dinh Diem becomes first president

1960 National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (Viet Cong) formed; Vietnam War begins

1961 U.S. military tests spraying of defoliants in Kon Tum Province in central Vietnam

1963 President Ngo Dinh Diem and U.S. President John F. Kennedy assassinated

1965 U.S. military begins bombing North Vietnam

1967 Spraying of defoliant reaches its peak between 1967 and 1969

1968 Concerted attack, Tet Offensive, launched by North Vietnam and the Viet Cong

1969 U.S. forces stationed in South Vietnam reach their peak of 540,000; North Vietnam’s Chairman Ho

Chi Minh dies

1971 Spraying of defoliants from U.S. military aircraft halted

1973 Paris Peace Accords. U.S. forces begin pulling out of Vietnam; Japan initiates diplomatic relations with

North Vietnam

1975 North Vietnamese forces take control of the South Vietnam capital of Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City);

Vietnam War ends

1976 North and South Vietnam unified; Socialist Republic of Vietnam established

1978 Vietnamese forces invade Cambodia

1979 Chinese forces invade Vietnam; China-Vietnam war begins

1986 Conjoined twins Viet and Duc come to Japan for emergency treatment; Communist Party of Vietnam

adopts Doi Moi economic reforms, introduces market economy

1993 Chemical Weapons Convention signed by 130 countries, including the U.S.: preamble includes

prohibition on the use of defoliants in war

1995 Normalization of relations between Vietnam and the U.S.

2003 Vietnam Association for Victims of Agent Orange/Dioxin (VAVA) established

2004 Representatives of VAVA file lawsuit against 37 chemical companies in U.S. federal district court; Day

for Vietnamese Victims of Agent Orange (August 10) established

2009 U.S. Supreme Court throws out VAVA suit for damages

2011 Vietnamese-U.S. joint project for the removal of dioxin gets underway at Da Nang International

Airport

(Originally published on June 19, 2012)