My Life: Interview with Keiji Nakazawa, author of “Barefoot Gen,” Part 2

Jul. 27, 2012

Child of a “traitor”

by Rie Nii, Staff Writer

Father speaks out:“ War is wrong”

When Mr. Nakazawa was born in 1939, the third son of six children in a house in the Funairi-honmachi district (now, Naka Ward, Hiroshima), Japan was in the midst of the Sino-Japanese war. The war had cast a long shadow over people’s lives.

My family had a painting business, but my father was actually an artist of Japanese-style paintings. Being an artist was synonymous with poverty, though, and my family was always struggling.

Above all, we were constantly hungry. At the time, uncooked rice was delicious to me. I would sneak a handful from the rice bin and share it with my younger brother. “It’s so good,” we would say as we gobbled it up. Of course, I think my mother noticed.

Mr. Nakazawa’s father became involved in the theater, too.

I heard that his involvement in the theater began when he went to Kyoto to undergo training in Japanese painting and lacquer work, with its sprinkles of gold and silver powder. It was a left-leaning troupe, to boot.

I was frightened to death when my father was taken away by a special police unit. My mother was trembling all over, her hair disheveled. Something terrible has happened, I thought. When my father didn’t come home, I asked my mother where he was. “He’s taking a physical for the military,” she said. “He was drafted to serve as a soldier.” I heard later that the members of the troupe had all been rounded up. For more than a year, my father was held in a detention center run by the Hiroshima Prefectural Government. When he finally came home, he was so weak he couldn’t even hold a rice bowl and chopsticks.

Mr. Nakazawa’s father also voiced his opposition to war at home.

At mealtimes, my siblings and I had to sit on our heels at a low round table and listen to my father’s lectures. “This war is wrong,” he told us. “Japan will lose, without a doubt.” He said that by the time I came of age, I would certainly see better days when we could eat bread, noodles, and white rice to our heart’s content. Though I was only a child at the time, it was because of his lectures that I came to realize that Japan was doing an awful thing by fighting that war.

The head of our neighborhood association came to our house almost every day to check up on my father. If the authorities discovered that there was a traitor in his area, the man would have been in serious trouble. Once the man went upstairs to my father’s workplace and soon came running back down at full speed. My father chased after him and they got into a fight on the street. The man was trying to squelch freedom of speech.

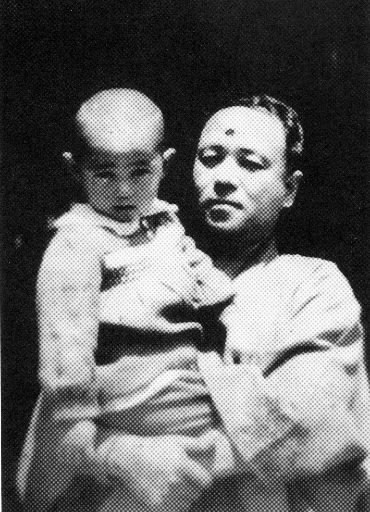

Though my father was a strait-laced man, he loved his children dearly. He would call me over, hold me in his arms, and rub his cheek, with its thick stubble, against mine.

(Originally published on July 4, 2012)