Vietnam: 50 years after the use of defoliants: Chemical weapons

Jul. 25, 2012

Chemical weapons: Long road to elimination

by Takamasa Kyoren, Staff Writer

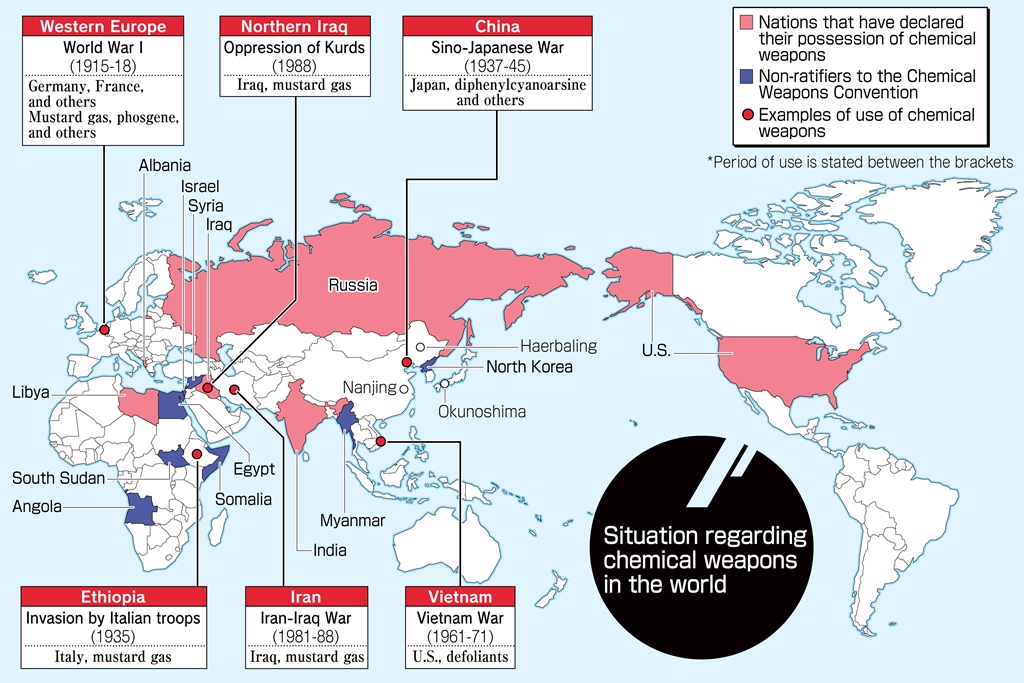

The defoliation carried out by the United States military during the Vietnam War has been etched in the history of mankind’s use of chemical weapons. Chemical weapons cause harm indiscriminately and result in lasting suffering. Because they are inexpensive to manufacture, they are sometimes referred to as the “poor man’s nuclear weapon.” The international community has sought a way to ban chemical weapons since the late 19th century. Nevertheless chemical weapons have repeatedly been used on the battlefield, and some nations still possess them. The disposal of abandoned chemical weapons has just begun. The history of Ohkunoshima in Takehara, Hiroshima Prefecture, where poison gas was manufactured, continues to proclaim the inhumanity of these weapons.

Removal and disposal: Way behind schedule

Ban yet to be ratified

The full-scale operation to remove dioxin from areas that were highly contaminated by defoliants sprayed by the U.S. military will get underway in Da Nang in central Vietnam this summer, 37 years after the end of the war. But defoliants are not classified as chemical weapons under the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC). For this reason, the disposal will proceed based on talks between the two countries. There are extensive contaminated areas like the one in Da Nang throughout Vietnam.

Chemical weapons not only kill or injure military personnel and civilians they also continue to cause serious disabilities. Defoliants do this as well. Toxic substances that have been stored or abandoned by military forces and others in many parts of the world have harmed both people and the environment.

In response to this, the CWC took effect in 1997. Its aim was the total eradication of existing chemical weapons within 10 years, with a maximum extension of five years. The convention also requires countries that abandoned chemical weapons they used to collect and dispose of them. The convention has been ratified by 188 countries including Japan and the U.S. Eight countries, including North Korea, Myanmar or Syria, have not ratified it.

Despite having ratified the convention, the U.S. has not assumed its obligation to dispose of the defoliants used during the Vietnam War because, although the preamble to the CWC states that the use of defoliants in war is prohibited, they are not clearly defined as chemical weapons.

According to the Foreign Ministry and other agencies, through March of this year seven countries, including the U.S. and Russia, have declared that they possess a total of 71,000 tons of chemical weapons. (The name of one country was not disclosed.) Through April of this year, the deadline for the elimination of all chemical weapons, approximately 52,000 tons (73 percent) of the weapons had been destroyed. The rate for the three countries that have not yet finished is 90 and 62 percent, respectively, for the U.S. and Russia, the major players in the Cold War, and 40 percent for Libya.

Meanwhile Japan is the only nation that is obligated to dispose of chemical weapons that were abandoned in wartime. Several countries have a responsibility to dispose of obsolete chemical weapons in their country.

According to the Cabinet Office, an estimated 300,000 to 400,000 poison gas canisters manufactured by the Imperial Japanese Army on Ohkunoshima are buried in Haerbaling on the outskirts of Dunhua in Jilin Province in northeast China. They were found during postwar development of the area, and many local residents have been harmed. In order to render these weapons harmless, Japan has built a disposal plant on the site. The effort to unearth the canisters and dispose of them is expected to finally get underway this fiscal year.

This project, which Japan undertook in 2000, is way behind schedule. Through June of this year, approximately 36,000 canisters had been disposed of in Nanjing. Initially the deadline for disposal was 2007, but it was pushed back to 2022. Through the end of fiscal year 2010, Japan had spent 86.1 billion yen on the collection and disposal of chemical weapons in China.

International rules on the banning of chemical weapons have been compromised in the past. As with nuclear weapons, if nations do not take steps toward the elimination of chemical weapons, humanity has no future.

Manufacture of poison gas by Japanese Imperial Army: Ohkunoshima in Takehara

Hiroshima University continues to shed light on effects on health

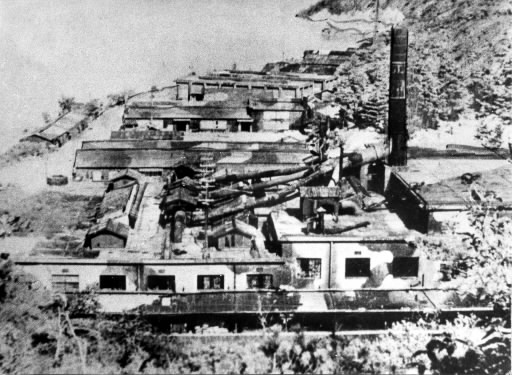

Ohkunoshima sits off the coast of Tadanoumi-cho in Takehara, Hiroshima Prefecture. During the war it was the site of a Japanese Imperial Army factory for the manufacture of poison gas, so the island was removed from maps. Those who were involved in the manufacture and postwar disposal of the poison gas have suffered effects for many years. Hiroshima University and others continue to work to shed light on the effects on health of the poison gas and conduct health checks. As of March of this year, a total of 2,605 people throughout Japan had been certified as suffering from the effects of the poison gas produced on Ohkunoshima.

The factory opened in 1929 as the Tadanoumi Weapons Manufacturing Plant of the Imperial Japanese Army’s Arsenal and Explosives Division. The plant adopted technology that France and Germany had used to produce a variety of chemical weapons during World War I. There were several factories on the island that produced mustard gas (yellow canisters), and sneezing gas made from arsenic (red canisters) and other weapons.

Production volume rapidly increased after the Sino-Japanese War broke out in 1937. According to materials compiled by the U.S. military, a total of 6,616 tons of solution for poison gas was produced on Ohkunoshima from the time of the plant’s opening through the end of the Second World War. It has been found that about 6,600 factory workers and mobilized students worked there.

The poison gas was used on the battlefield in China. After the war, poison gas that had been stored on Ohkunoshima was disposed of under the direction of the British military. Some of it was buried in air raid shelters on the island while some was dumped into the sea around the island, and the environment is still affected.

Because a veil of secrecy surrounded the effects of the poison gas, aid was delayed. The effort to shed light on the effects from a medical standpoint did not begin until 1952. Professors at Hiroshima University began conducting group health checks of the residents of Tadanoumi-cho. They also looked into the causes of death of the residents. As a result of their persistent efforts, they were able to confirm a relationship between poison gas and the high incidence of respiratory disease in the area.

In 1954 special measures to provide aid to those suffering from disabilities as a result of their exposure to poison gas were implemented. Pensions and coupons for health care were provided to those who were certified as having disabilities. In 1969 aid was extended to some patients who had not been certified. Masayuki Yamauchi, 67, is the director of the Poison Gas Island Institute of History, a citizens’ group in Takehara. “Many people both in Japan and abroad are suffering from the aftereffects of poison gas,” he said. “The state should take responsibility. I will continue to call for the elimination of chemical weapons so that this situation will never be repeated.”

Need to take an interest in clean-up

by Keiichi Tsuneishi, Professor, Faculty of Business Administration, Kanagawa University

Chemical weapons have been called the “poor man’s nuclear weapon.” Many of the chemicals used in their manufacture are used by civilians and are easy to obtain. Production facilities need not be large, so chemical weapons can be manufactured at a much lower cost than nuclear weapons.

The international community has created a framework for the abolition of chemical weapons through the Chemical Weapons Convention and other measures. The existing chemical weapons were to be eliminated in accordance with the terms of the convention. But, although the initial deadline has already passed, the weapons have not yet been eliminated.

The fearfulness of chemical weapons lies in the fact that no one knows when their effects will become apparent and the fact that they cause years of suffering. This is true of the defoliants used in Vietnam as well as the poison gas manufactured by the Imperial Japanese Army on Ohkunoshima and used by them. The people who used the poison gas or were involved in its manufacture are still suffering from disabilities decades after the end of the war. Others are suffering from the genetic effects of the weapons or through contact with weapons that have been abandoned.

Naturally, the countries that manufactured and used chemical weapons bear full responsibility for that. That responsibility amounts to providing aid for the victims and disposing of abandoned weapons. In this regard, we should take a greater interest in the disposal of chemical weapons that Japan is carrying out in China. In order to learn about the mistakes that we made and in order to ensure that the same tragedy is not repeated, it is essential that we confront the issue of clean-up. If we can’t do that, we can not win the trust of the international community.

There are also some things about the aftereffects of chemical weapons that remain unclear. Whether we abandon patients on that account or consistently stand by them will be called into question.

The removal of dioxin from Vietnam will require a great deal of time and money. I will be interested to see whether or not the U.S., which bears the responsibility for this, will address the problem in a sincere manner.

The basic purpose of science is to enrich people’s lives. But progress in science and technology has led to the development of chemical weapons one after another. We must examine the burdens borne by science and continue to keep a close watch on the state and those in authority.

Keiichi Tsuneishi

Born in Tokyo in 1943. Graduate of Tokyo Metropolitan University. Assumed his present position in 1989 after serving as a professor at Nagasaki University and in other posts. Specializes in the history of science. Known for his research on the Japanese Imperial Army’s Unit 731. Continues to consider the social mission of scientists. Author of various books including “Chemical Weapon Crimes.”

First appear in World War I: Development by various nations follows

Chemical weapons were first used in modern warfare about 100 years ago. In 1915 during World War I (1914-1918) the German military used large quantities of chlorine gas on Allied forces at Ypres in Belgium. Approximately 5,000 people are believed to have died from the poisonous gas. Later mustard gas and other chemical weapons were developed.

The militaries of France and England retaliated with chemical weapons. Phosgene and other highly toxic lethal gases were developed one after another. A total of 13,500 tons of 30 types of poison gas were used in the First World War. Thus it was also called the “chemical war.” The number of those killed by chemical weapons came to 100,000.

In 1925 the Geneva Protocol, which prohibited the use of poison gas, was adopted, but neither Japan nor the U.S. ratified it. Under the provisions of the protocol, neither the production nor storage of poison gas was prohibited, and development proceeded in many nations. Mustard gas was first sprayed from the air in 1935 by Italy when it invaded Ethiopia.

At the end of World War II, the U.S. drew up a plan to use defoliants and poison gas in an attack on the Japanese mainland, but their use was made unnecessary by the atomic bombings. During the Vietnam War (1960-1975), approximately 80 million liters of defoliants containing highly toxic dioxin were used.

During the Iran-Iraq War from 1980 to 1988 Iraq used mustard gas, killing many people on the Iranian side. Several thousand Kurds in Iraq also died when the government used poison gas indiscriminately against them.

Syria is one of the nations that has not ratified the Chemical Weapons Convention. It is suspected of possessing chemical weapons, and there is concern that they will be used in Syria, where a civil war is going on.

History Related to Chemical Weapons

1899 Hague Convention signed. Use of toxic substances in warfare banned.

1915 German military makes extensive use of chlorine gas in World War I.

1917 German military develops mustard gas and other chemical weapons and uses them in Belgium.

1925 Geneva Protocol signed. Use of biological and chemical weapons in warfare banned. Japan, the U.S.

and Germany decline to ratify the protocol.

1929 Poison gas factory opens on Ohkunoshima in Takehara.

1930 Imperial Japanese Army uses poison gas for the first time to quell rioting by Taiwanese.

1935 Italy sprays mustard gas from the air during its invasion of Ethiopia.

1937 Sino-Japanese War begins. Volume of poison gas produced on Ohkunoshima rapidly increases.

Japanese Imperial Army makes extensive use of poison gas in actual warfare in various parts of

China.

1945 World War II ends. Japanese Imperial Army abandons poison gas. In postwar disposal, Japanese

Army’s poison gas is dumped by the U.S. military and others in various areas both in Japan and

overseas.

1946 British military disposes of poison gas on Ohkunoshima and in other areas. Some is dumped into the

sea off the coast of Kochi Prefecture.

1961 U.S. military conducts test spraying of defoliants in central Vietnam.

1967 Ohkunoshima Poison Gas Sufferers Liaison Council formed.

1969 Resolution banning the use of biological and chemical weapons adopted by the United Nations

General Assembly.

1971 Final spraying of defoliants by U.S. military aircraft.

1975 U.S. ratifies Geneva Protocol.

1981 Iraq begins using mustard gas and other chemical weapons in the Iran-Iraq War.

1988 Iraq uses poison gas to suppress Kurds within its borders.

1990 U.S. and Soviet Union sign U.S.-Soviet Chemical Weapons Accord.

1991 Japan sends first team to China to investigate abandoned gas canisters.

1993 Chemical Weapons Convention signed by 130 countries, including Japan and the U.S.

1994 Matsumoto sarin incident in Nagano Prefecture

1995 Sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway. Metal objects believed to be poison gas canisters used by the

Japanese Imperial Army found in Lake Kussharo in Hokkaido.

2000 Japan begins digging up and collecting abandoned chemical weapons in China’s Heilongjiang

Province.

2003 High concentration of an organic arsenic compound believed to have come from poison gas weapons

used by the Japanese Imperial Army detected in well water in Kamisu-machi (now the city of

Kamisu) in Ibaraki Prefecture. Twenty residents, including children, complain of symptoms of

poisoning.

2009 Suspicious objects believed to be a poison gas weapons found on the ocean floor off the coast of

Ohkunoshima. The following year the Environment Ministry states that they are almost certainly

canisters of sneezing gas.

2010 Disposal of chemical weapons abandoned by the Japanese Imperial Army begins at a mobile disposal

facility in Nanjing, China.

2011 Removal of dioxin from highly contaminated areas in Vietnam begins. The dioxin was contained in

defoliants sprayed over the areas.

2012 Removal of dioxin in Vietnam goes into full swing. Matter of arsenic contamination in Kamisu is

settled when Ibaraki Prefecture pays a total of 60 million yen to residents. Disposal of approximately

36,000 chemical weapons abandoned in Nanjing, China completed.

(Originally published on July 18, 2012)