Vietnam: 50 years after the use of defoliants, Part 3: Path to a solution, Article 2

Jul. 25, 2012

Article 2: Veil of military secrecy

“Used in Okinawa”: Facts obscure

by Takamasa Kyoren, Staff Writer

Residents’ growing concern: Need for disclosure of information

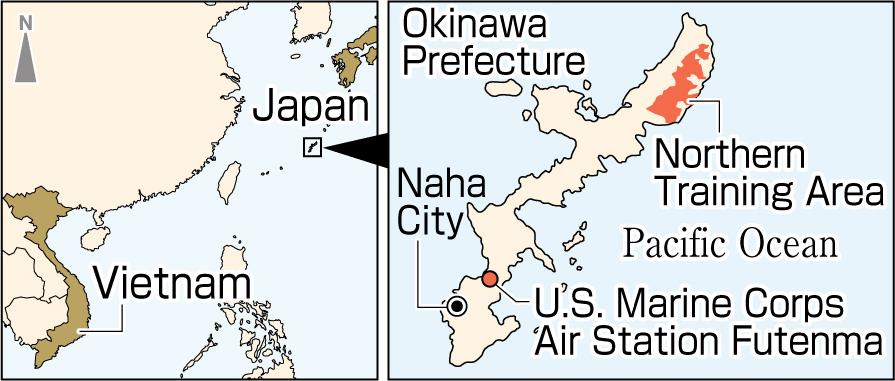

Amid the ongoing turmoil surrounding the U.S. Marine Corps Air Station Futenma, the issue of defoliants has emerged in Okinawa Prefecture as the result of an article carried by an English-language newspaper last summer. The paper reported that former U.S. military personnel who were stationed on Okinawa stated that they used and stored defoliants containing highly toxic dioxin at U.S. military facilities in the prefecture during the Vietnam War in the 1960s and 1970s.

One of the nine facilities referred to in their statements is a mountainous area of the main island of Okinawa that was formerly part of the Northern Training Area (NTA) at the U.S. Marine Corps Jungle Warfare Training Center. I visited there prior to the 40th anniversary of Okinawa’s 1972 reversion to Japan. The reservoirs at the five dams in the area around the facility are referred to as “Okinawa’s water jug.”

One part of the area consists of reddish brown dirt with no vegetation. Yoshitami Oshiro, 71, a member of the city assembly in Nago, had suspected that this barren land was the result of defoliants. “When I learned about the statements of the former military personnel, I thought to myself, ‘Sure enough,’” he said.

Other facilities that were cited in the statements include Camp Schwab in Nago and Kadena Air Base in the city of the same name. The prefecture and local municipalities immediately pressed the Japanese government to ascertain the facts.

But the central government merely continues to state that it has been told by the U.S. that there are no documents indicating that defoliants were brought onto Okinawa. There is no indication that the Japanese government intends to launch an independent investigation.

Inconsistency with U.S. position

During the war, Okinawa served as a base for sending materiel and military personnel to Vietnam. U.S. Marines conducted anti-guerrilla warfare training in the northern part of the island of Okinawa, whose terrain is jungle-like, and defoliants are believed to have been used. Suspicions of their use on Okinawa have come and gone.

There are facts that contradict the U.S. position that defoliants were not brought onto Okinawa. In 2007 official documents of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs revealed that former military personnel who sprayed defoliants at the NTA and other facilities in 1960 and 1961 had been certified as suffering from prostate cancer as an aftereffect. The department has paid compensation to at least three veterans formerly stationed in Okinawa who have been acknowledged as suffering from health problems related to defoliants.

Every year Okinawa Prefecture conducts water quality surveys in the vicinity of the U.S. bases in accordance with the Act on Special Measures against Dioxins. So far no results have exceeded the environmental standard, but no surveys are conducted on the premises of military bases because, under the terms of the U.S-Japan Status of Forces Agreement, facilities and districts provided to the U.S. are under the administration of the U.S. military.

The city of Nago and the town of Chatan have conducted their own interviews of former base employees and have tested the soil and groundwater. But their budgets and the scope of their testing are very limited. The testing has been criticized by some as just “going through the motions.”

Concern about further harm

Local residents are faced with the barrier posed by the military. The U.S. Marine Corps Air Station in the city of Iwakuni in Yamaguchi Prefecture also served as a base for the dispatch of troops to Vietnam during the war. There were suspicions that biological and chemical weapons as well as nuclear-related materials were brought onto the base and stored there. But the facts remain obscure.

“If the truth about the environmental pollution and the health hazards is not conveyed to the residents, further harm and problems will result,” said Yoshiyasu Iha, 70, a resident of the city of Uruma and co-president of the Citizens’ Network for Biological Diversity in Okinawa.

The government of Vietnam has only disclosed three of the 28 sites that are contaminated by high levels of dioxin. Most are believed to be military land. Environmental surveys that were conducted by researchers from Vietnam and abroad after the war did not include military land.

Komichi Ikeda, vice director of the Environment Research Institute, Inc. in Tokyo, has inspected the land that was formerly part of the NTA. “The environmental pollution covers a wide area that spans both military land and private property,” he said. “Even if it’s military-related, municipalities and the central government should disclose the information and put priority on the safety of the residents in the area.”

(Originally published on July 19, 2012)