My Life: Interview with TV Director Yasuko Isono, Part 5

Jun. 26, 2013

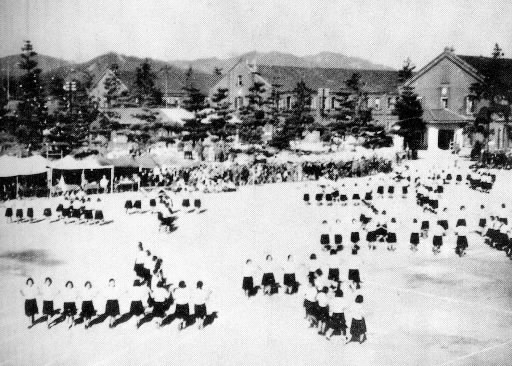

First Prefectural Girls’ High School

by Takahiro Yamase, Staff Writer

Comforting one another’s A-bomb suffering

Yasuko Isono left her hometown of Etajima at the age of 12 and entered First Prefectural Girls’ High School in Hiroshima in the spring of 1946.

The education provided in the countryside before the war was very rigid and one-sided. But the education I received in Hiroshima after the war was very different. I really enjoyed it. We learned modern history and studied the literature of America and Europe, too. I was able to see a world that we could never glimpse during the war.

In particular, singing songs in English, which was forbidden during the war, was wonderful. I wondered why we were fighting against America, where they spoke English.

A large number of students who were a year older than Ms. Isono were killed in the bombing. Many classmates became orphans.

All of my friends were suffering because of the bombing, but we didn’t talk about it with one another. I didn’t think talking about our troubles would help, and somehow would just make us feel more miserable. I myself lost a number of relatives, but I would never talk about it. This is partly because we believed in the aesthetic in which people didn’t openly express their suffering. We all pretended to be living cheerfully as happy girls in our early teens.

But we still noticed when our friends felt some emotional distress. Then we would gently comfort them. That was an unspoken rule we naturally came to make.

When I was 14, First Girl’s High School changed its name to Yuho High School. That spring I became a third-year student in the school’s junior high. A year later, Yuho High School changed again, becoming Minami High School. I entered the high school without taking entrance exams.

Minami High School was a co-ed school. I began to be aware of male ways of thinking, and their views on philosophy and ethics, and found that these were different from those of women. Happiness for women involved the idea of getting married and becoming a housewife, while men made dogged efforts to accomplish their own goals. In addition, the new constitution took effect. I started to feel that a woman could pursue a career just like a man.

Ms. Isono then sought higher education in Tokyo.

Moving from the island of Etajima to Hiroshima broadened my horizons a lot. So Tokyo, I thought, which was a much bigger city, would broaden my horizons even further.

I guess I was especially ambitious in those days. I took the entrance exams for a university in Tokyo, but I wasn’t accepted. I spent a year preparing for the next round of entrance exams, but I failed again. I thought I wouldn’t be able to improve if I continued to study in Hiroshima, so I moved to Tokyo, all by myself, and attended a cram school there. Back then, it was unthinkable for a woman to move to Tokyo by herself. But my father let me do what I wanted, saying, “She won’t change her mind once she’s made a decision.”

(Originally published on December 4, 2010)

by Takahiro Yamase, Staff Writer

Comforting one another’s A-bomb suffering

Yasuko Isono left her hometown of Etajima at the age of 12 and entered First Prefectural Girls’ High School in Hiroshima in the spring of 1946.

The education provided in the countryside before the war was very rigid and one-sided. But the education I received in Hiroshima after the war was very different. I really enjoyed it. We learned modern history and studied the literature of America and Europe, too. I was able to see a world that we could never glimpse during the war.

In particular, singing songs in English, which was forbidden during the war, was wonderful. I wondered why we were fighting against America, where they spoke English.

A large number of students who were a year older than Ms. Isono were killed in the bombing. Many classmates became orphans.

All of my friends were suffering because of the bombing, but we didn’t talk about it with one another. I didn’t think talking about our troubles would help, and somehow would just make us feel more miserable. I myself lost a number of relatives, but I would never talk about it. This is partly because we believed in the aesthetic in which people didn’t openly express their suffering. We all pretended to be living cheerfully as happy girls in our early teens.

But we still noticed when our friends felt some emotional distress. Then we would gently comfort them. That was an unspoken rule we naturally came to make.

When I was 14, First Girl’s High School changed its name to Yuho High School. That spring I became a third-year student in the school’s junior high. A year later, Yuho High School changed again, becoming Minami High School. I entered the high school without taking entrance exams.

Minami High School was a co-ed school. I began to be aware of male ways of thinking, and their views on philosophy and ethics, and found that these were different from those of women. Happiness for women involved the idea of getting married and becoming a housewife, while men made dogged efforts to accomplish their own goals. In addition, the new constitution took effect. I started to feel that a woman could pursue a career just like a man.

Ms. Isono then sought higher education in Tokyo.

Moving from the island of Etajima to Hiroshima broadened my horizons a lot. So Tokyo, I thought, which was a much bigger city, would broaden my horizons even further.

I guess I was especially ambitious in those days. I took the entrance exams for a university in Tokyo, but I wasn’t accepted. I spent a year preparing for the next round of entrance exams, but I failed again. I thought I wouldn’t be able to improve if I continued to study in Hiroshima, so I moved to Tokyo, all by myself, and attended a cram school there. Back then, it was unthinkable for a woman to move to Tokyo by herself. But my father let me do what I wanted, saying, “She won’t change her mind once she’s made a decision.”

(Originally published on December 4, 2010)