Living in Kawauchi, “Town of the Atomic Bomb” [1-1]

Jul. 17, 2013

Part 1: Since that fateful day

Article 1: The last A-bomb widow

by Michiko Tanaka, Staff Writer

Wives who lost husbands and breadwinners: Supporting one another through tough times

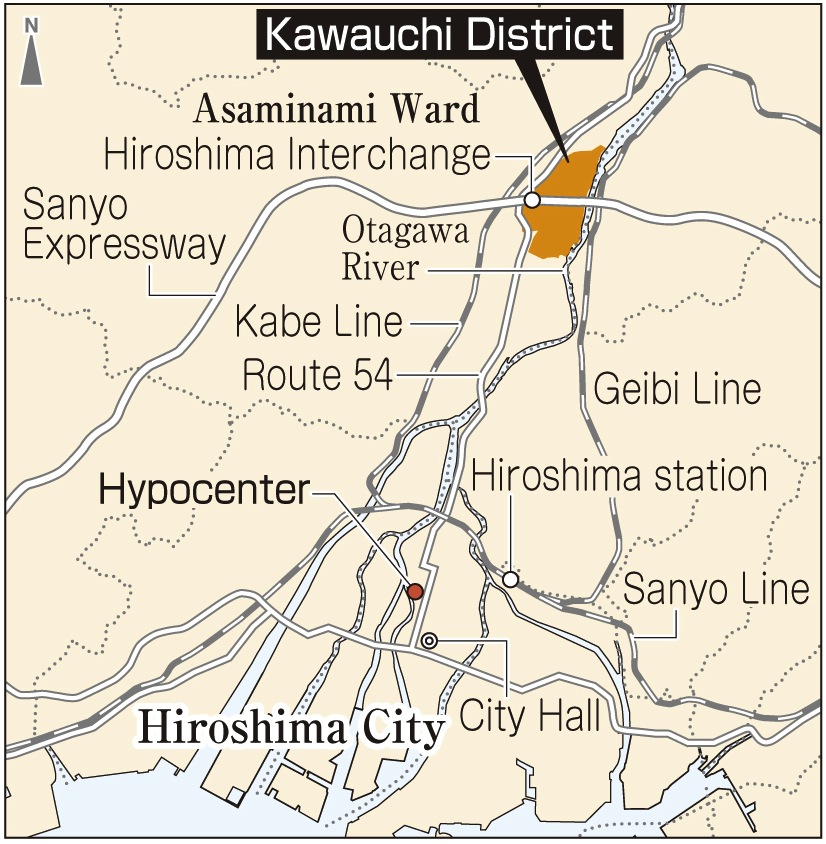

Kawauchi (located in what is now Asaminami Ward, Hiroshima) was dubbed “The A-bomb Town,” despite the fact that it lay on the outskirts of the city. In all, more than 70 women who lost their husbands to the atomic bombing lived in Kawauchi. They worked hard in the fields and endured their hardships. Now, in the 68th summer since the bombing, Masako Nomura, 92, is the only surviving widow. To reflect on the repercussions of this one bomb to the people here, the Chugoku Shimbun explored the Kawauchi area on foot.

Early in the morning of July 6, one month before the anniversary of the bombing, Ms. Nomura left her home in Kawauchi. Leaning her slight body on a walker, she pushed it slowly along toward Jogyoji Temple, roughly 400 meters on foot. For the past 68 years, she has visited the temple on the 6th of every month to observe the day of her husband’s death. “No matter how many years go by, I can’t forget that day,” she said.

About 200 people from her town lost their lives in the A-bomb attack of August 6, 1945. They were members of the Kawauchi Volunteer Fighting Corps and, as part of the war effort demanded by the Japanese government, were helping to demolish buildings in downtown Hiroshima to create a fire lane. In the aftermath of the blast, their wives and family members began holding a memorial service on the 6th of each month at Jogyoji Temple, starting on September 6.

Widows once filled the temple’s spacious hall, but they passed away, one after another. With the death of Haruko Sumii this past March, at the age of 101, Ms. Nomura is now the only surviving widow. During the service on July 6, she recalled how her husband looked that fateful day, and chanted a sutra with the head priest, Atsushi Sakayama, 64.

When Ms. Nomura was 21, she married Shinichi, six years her elder, and moved from the neighboring town to live with his family. The couple both came from farm families, and her husband had lost part of his right index finger while threshing rice. Because he was unable to shoot a gun, he was exempt from the draft.

“He was handsome and kind,” Ms. Nomura said. In 1943 they had a baby girl. When the baby began to crawl, Shinichi would follow her on his hands and knees, sporting a smile. The family was not wealthy, but they led a happy life.

On the morning of August 6, Shinichi went to help demolish homes in the Nakajima-shinmachi area (now part of Nakajima-cho in Naka Ward), on the south side of today’s Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. After the blast, he was rescued and placed on a river boat, which brought him home, a miracle in itself. But he had burns all over his body. One torn shoe, cloth footwear with a rubber sole, was the only thing he had on. “Give me water,” he groaned as he writhed in agony. “My stomach hurts.” Recalling the time, Ms. Nomura said, “Even now I get choked up when I think of him. It was living hell for him.” Shinichi died that night.

But those who were left behind were forced to endure their own hellish life. Ms. Nomura, who was 24, was now responsible for her two-year-old daughter and her sickly father-in-law. Each morning she woke before dawn and worked the small plot of farmland that her husband had left behind. But much of the rice and vegetables she grew had to be sold to the government for next to nothing.

Once her daughter entered elementary school, Ms. Nomura found work as a day laborer, a job for widows provided by the town government. In muddy water that was chest deep, she cut down cattails, which were used to make matting. It was an arduous task, but she was paid more than 300 yen under a performance-based system. In those days, the starting monthly salary for a college-educated public official was less than 10,000 yen. She swung a sickle as if competing with the other workers.

The widows, though, were treated coldly. “Some people called Kawauchi a town of A-bomb widows,” she said. She was unable to relax, mentally or physically, and in times of exhaustion, she would look at her daughter’s sleeping face and weep. “Sometimes I thought of drowning myself in the river,” she said, but the support of other widows, facing the same situation, enabled her to endure. “All of them had great perseverance. We helped each other go on.”

Ms. Nomura now lives peacefully with her daughter Masae, 70, and Masae’s husband. “Today is an age of affluence, and no one can understand how we lived back then,” she said. Still, she feels she must pray for peace. “I hate war. Young people must get along together and preserve peace.” Then she closed her eyes and joined her wrinkled hands in prayer.

(Originally published on July 7, 2013)

Article 1: The last A-bomb widow

by Michiko Tanaka, Staff Writer

Wives who lost husbands and breadwinners: Supporting one another through tough times

Kawauchi (located in what is now Asaminami Ward, Hiroshima) was dubbed “The A-bomb Town,” despite the fact that it lay on the outskirts of the city. In all, more than 70 women who lost their husbands to the atomic bombing lived in Kawauchi. They worked hard in the fields and endured their hardships. Now, in the 68th summer since the bombing, Masako Nomura, 92, is the only surviving widow. To reflect on the repercussions of this one bomb to the people here, the Chugoku Shimbun explored the Kawauchi area on foot.

Early in the morning of July 6, one month before the anniversary of the bombing, Ms. Nomura left her home in Kawauchi. Leaning her slight body on a walker, she pushed it slowly along toward Jogyoji Temple, roughly 400 meters on foot. For the past 68 years, she has visited the temple on the 6th of every month to observe the day of her husband’s death. “No matter how many years go by, I can’t forget that day,” she said.

About 200 people from her town lost their lives in the A-bomb attack of August 6, 1945. They were members of the Kawauchi Volunteer Fighting Corps and, as part of the war effort demanded by the Japanese government, were helping to demolish buildings in downtown Hiroshima to create a fire lane. In the aftermath of the blast, their wives and family members began holding a memorial service on the 6th of each month at Jogyoji Temple, starting on September 6.

Widows once filled the temple’s spacious hall, but they passed away, one after another. With the death of Haruko Sumii this past March, at the age of 101, Ms. Nomura is now the only surviving widow. During the service on July 6, she recalled how her husband looked that fateful day, and chanted a sutra with the head priest, Atsushi Sakayama, 64.

When Ms. Nomura was 21, she married Shinichi, six years her elder, and moved from the neighboring town to live with his family. The couple both came from farm families, and her husband had lost part of his right index finger while threshing rice. Because he was unable to shoot a gun, he was exempt from the draft.

“He was handsome and kind,” Ms. Nomura said. In 1943 they had a baby girl. When the baby began to crawl, Shinichi would follow her on his hands and knees, sporting a smile. The family was not wealthy, but they led a happy life.

On the morning of August 6, Shinichi went to help demolish homes in the Nakajima-shinmachi area (now part of Nakajima-cho in Naka Ward), on the south side of today’s Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. After the blast, he was rescued and placed on a river boat, which brought him home, a miracle in itself. But he had burns all over his body. One torn shoe, cloth footwear with a rubber sole, was the only thing he had on. “Give me water,” he groaned as he writhed in agony. “My stomach hurts.” Recalling the time, Ms. Nomura said, “Even now I get choked up when I think of him. It was living hell for him.” Shinichi died that night.

But those who were left behind were forced to endure their own hellish life. Ms. Nomura, who was 24, was now responsible for her two-year-old daughter and her sickly father-in-law. Each morning she woke before dawn and worked the small plot of farmland that her husband had left behind. But much of the rice and vegetables she grew had to be sold to the government for next to nothing.

Once her daughter entered elementary school, Ms. Nomura found work as a day laborer, a job for widows provided by the town government. In muddy water that was chest deep, she cut down cattails, which were used to make matting. It was an arduous task, but she was paid more than 300 yen under a performance-based system. In those days, the starting monthly salary for a college-educated public official was less than 10,000 yen. She swung a sickle as if competing with the other workers.

The widows, though, were treated coldly. “Some people called Kawauchi a town of A-bomb widows,” she said. She was unable to relax, mentally or physically, and in times of exhaustion, she would look at her daughter’s sleeping face and weep. “Sometimes I thought of drowning myself in the river,” she said, but the support of other widows, facing the same situation, enabled her to endure. “All of them had great perseverance. We helped each other go on.”

Ms. Nomura now lives peacefully with her daughter Masae, 70, and Masae’s husband. “Today is an age of affluence, and no one can understand how we lived back then,” she said. Still, she feels she must pray for peace. “I hate war. Young people must get along together and preserve peace.” Then she closed her eyes and joined her wrinkled hands in prayer.

(Originally published on July 7, 2013)