Living in Kawauchi, “Town of the Atomic Bomb”

Jul. 17, 2013

Strong women endure misery: Husbands in volunteer corps killed in A-bombing

Pulling together and engaging in hard labor

by Michiko Tanaka and Yuichi Ishii, Staff Writers

Once a farming area, Kawauchi, located in Hiroshima’s Asa Minami Ward, is now a residential area. After their husbands were killed in the atomic bombing, the women of the community led lives of hardship. In this series the Chugoku Shimbun recounts the stories of those women, who themselves were victims of the A-bombing.

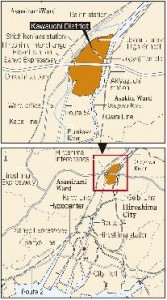

Kawauchi is located approximately 10 km north of the city center. Known as a production center for Chinese cabbage, the community lies between the Ota and Furukawa rivers. Blessed with fertile soil, Kawauchi has been a farming area since before the war. During the war, vegetables grown in Kawauchi were shipped to soldiers and sailors in Hiroshima and Kure. The community served as the “pantry” of these military towns.

Kawauchi covers an area of 174 hectares. In 1970, 101 hectares of that was farmland. But the farmland rapidly dwindled as the area was developed, and only 23 hectares of Kawauchi is farmland today. Now the area serves as a bedroom community for Hiroshima, with its population of 1.2 million. As of the end of May, there were 5,437 households in Kawauchi with a population of 14,154.

Mikio Kanda, 90, a local ethnologist, says that the soil of Kawauchi is “fraught with the horrors of the war.” Starting in 1980 Mr. Kanda regularly visited Kawauchi for a year and a half, and in 1982 he compiled ““I Lost My Husband to the A-Bomb,” a book consisting of the accounts of 19 women who were widowed by the atomic bombing.

After the war, Mr. Kanda went to work for the prefectural government, and starting in the 1950s he served as an adviser to farming communities in the prefecture, including Kawauchi. He was moved by the women of the town, who worked hard to maintain the fields in the community amid the lack of men. “The atomic bomb changed the way of life of those women,” Mr. Kanda said. “I wanted to preserve their accounts of their experiences as survivors of the war.” Each of the women talked to him about their hardships.

The fate of Kawauchi was decided in July 1945 when the town’s Volunteer Fighting Corps received its orders: to demolish buildings in downtown Hiroshima and to build an airfield in Yachiyo-cho (now the city of Aki Takata). At the time, the town consisted of the communities of Nukui and Naka Joshi, and the Volunteer Fighting Corps was divided into two units, one from each of these areas. The unit from Nukui was working on the demolition on August 6.

The men were sent to work in Nakajima Shin-machi (now part of Nakajima-cho, Naka Ward), just south of where Peace Memorial Park is today. This area was almost directly below the hypocenter. All of those working on the demolition of buildings died. According to a list of the members of the Volunteer Fighting Corps compiled by Kawauchi in 1952, 183 men were killed. Some people believe the total number of deaths exceeded 200.

At the time, there were approximately 550 households in Kawauchi, which had a population of about 2,300. About 10 percent of the population was killed in the atomic bombing. There were about equal numbers of men and women, and 80 percent of the men were in their 40s or 50s.

Many families were left without their breadwinner. The wives of those who were killed repeatedly made the trip of more than 10 km into the city center and looked through stacks of bodies in search of their husbands. Many of them never found their husbands’ remains.

Days of hardship awaited them. They had no time to grieve. Pushing themselves, the women donned their husbands’ work clothes and went out into the fields that had been left to them, to survive and to feed their children.

They got up before dawn, loaded vegetables onto large two-wheeled carts and took them into town. Carrying pails, they went door to door collecting night soil in exchange for vegetables.

The women also turned out for day labor related to the rebuilding of the city. They received no aid from the government until 1953 when they became eligible for an annual payment of 3,000 yen in condolence money.

But they pulled together and carried on. In 1949 they formed the White Plum Society, a mutual aid organization. The society held sewing classes, and members went clam-digging together and encouraged each other. On the 6th of every month, they held a memorial service at Jogyoji, a local temple, and wept together.

Of the 19 women who were interviewed by Mr. Kanda, only one is still living: Masako Nomura, 92. “Those women made Kawauchi what it is today,” Mr. Kanda said. That history must not be forgotten.

Developments related to the Kawauchi area and the women who lost their husbands in the A-bombing

April 1889: Town of Kawauchi formed by merger of Nukui and Naka Joshi

March 1945: Volunteer Corps created through Cabinet resolution

May 1945: Hiroshima Prefecture directs municipalities to form volunteer corps

July 1945: Prefecture orders Kawauchi Volunteer Fighting Corps to participate in demolition of buildings in Hiroshima’s city center

August 1945: U.S. drops atomic bomb on Hiroshima

September 1945: Monthly memorial services at Jogyoji Temple begin; joint memorial service held in Kawauchi

May 1947: Constitution of Japan takes effect

February 1949: White Plum Society, a mutual aid organization for women of Kawauchi who lost their husbands in the war, formed

September 1949: Hiroshima Widows’ Association (now Hiroshima Single Parents and Children’s Welfare Association) formed

April 1952: Act on Relief of War Victims and Survivors enacted; families of Volunteer Fighting Corps members eligible for survivor condolence money

February 1953: White Plum Society erects monument to local war dead and other victims of the war on grounds of Kawauchi Elementary School

July 1955: Kawauchi, Midorii, Yagi merge to form Sato-cho

May 1958: Act on Relief of War Victims and Survivors revised; families of Volunteer Fighting Corps members eligible for survivor’s benefit

April 1963: Special Survivor Benefit Act for wives of war dead and others enacted; wives of Volunteer Fighting Corps members eligible for special survivor’s benefit

August 1964: Monument to Volunteer Fighting Corps erected in Peace Memorial Park

March 1973: Sato-cho merges with the City of Hiroshima

April 1980: Hiroshima becomes a “city designated by government ordinance”; with creation of wards, Kawauchi becomes part of Asa Minami Ward

February 1982: “I Lost My Husband to the A-Bomb” by Mikio Kanda published

February 1988: Hiroshima interchange of Sanyo Expressway opens in Kawauchi

October 1999: The Furukawa District, which includes Kawauchi, is created as part of city’s re-demarcation

October 2010: According to national census, population of Kawauchi area is 13,847, six times its February 1944 population of 2,375

Keywords

Volunteer Fighting Corps

In 1945, at the end of World War II, in anticipation of a decisive battle on the Japanese mainland, the government formed Volunteer Citizen Corps (later renamed the Volunteer Fighting Corps) in communities and at companies throughout the country. All civilian men aged 12 to 65 and women aged 12 to 45 were members. They engaged in the demolition of buildings and civil defense activities. According to an estimate by the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, a total of 11,633 members of Volunteer Fighting Corps from the city of Otake and other areas surrounding Hiroshima had been mobilized in the city on the day of the atomic bombing. Of these, 4,632 are believed to have been killed.

Government relief for survivors of Volunteer Fighting Corps members

Families of members of the Volunteer Fighting Corps who were killed became eligible for relief from the government with the passage of the Act on Relief of War Victims and Survivors in 1952. For 10 years starting in 1953 the national government paid annual survivor condolence money of 3,000 yen to the families of victims. With the revision of the relief act in 1958, members of the Volunteer Fighting Corps were classified as “paramilitary,” and their families became eligible for survivor benefits. Following this revision, annual survivor benefits of 25,500 yen were paid to the families of members of the Volunteer Fighting Corps, half the amount paid to the families of military personnel and civilian employees of the military. In 1963 the five-year limit on the payment of benefits was abolished. Starting in 1974, survivors of members of the military received the same amount as survivors of civilian employees, and payments were increased in stages in line with inflation. The current annual survivor’s benefit is just under 2 million yen. Since 1963 a special survivor benefit of 200,000 yen per year has also been paid to the wives of those who died in the war.

(Originally published on July 7, 2013)

Pulling together and engaging in hard labor

by Michiko Tanaka and Yuichi Ishii, Staff Writers

Once a farming area, Kawauchi, located in Hiroshima’s Asa Minami Ward, is now a residential area. After their husbands were killed in the atomic bombing, the women of the community led lives of hardship. In this series the Chugoku Shimbun recounts the stories of those women, who themselves were victims of the A-bombing.

Kawauchi is located approximately 10 km north of the city center. Known as a production center for Chinese cabbage, the community lies between the Ota and Furukawa rivers. Blessed with fertile soil, Kawauchi has been a farming area since before the war. During the war, vegetables grown in Kawauchi were shipped to soldiers and sailors in Hiroshima and Kure. The community served as the “pantry” of these military towns.

Kawauchi covers an area of 174 hectares. In 1970, 101 hectares of that was farmland. But the farmland rapidly dwindled as the area was developed, and only 23 hectares of Kawauchi is farmland today. Now the area serves as a bedroom community for Hiroshima, with its population of 1.2 million. As of the end of May, there were 5,437 households in Kawauchi with a population of 14,154.

Mikio Kanda, 90, a local ethnologist, says that the soil of Kawauchi is “fraught with the horrors of the war.” Starting in 1980 Mr. Kanda regularly visited Kawauchi for a year and a half, and in 1982 he compiled ““I Lost My Husband to the A-Bomb,” a book consisting of the accounts of 19 women who were widowed by the atomic bombing.

After the war, Mr. Kanda went to work for the prefectural government, and starting in the 1950s he served as an adviser to farming communities in the prefecture, including Kawauchi. He was moved by the women of the town, who worked hard to maintain the fields in the community amid the lack of men. “The atomic bomb changed the way of life of those women,” Mr. Kanda said. “I wanted to preserve their accounts of their experiences as survivors of the war.” Each of the women talked to him about their hardships.

The fate of Kawauchi was decided in July 1945 when the town’s Volunteer Fighting Corps received its orders: to demolish buildings in downtown Hiroshima and to build an airfield in Yachiyo-cho (now the city of Aki Takata). At the time, the town consisted of the communities of Nukui and Naka Joshi, and the Volunteer Fighting Corps was divided into two units, one from each of these areas. The unit from Nukui was working on the demolition on August 6.

The men were sent to work in Nakajima Shin-machi (now part of Nakajima-cho, Naka Ward), just south of where Peace Memorial Park is today. This area was almost directly below the hypocenter. All of those working on the demolition of buildings died. According to a list of the members of the Volunteer Fighting Corps compiled by Kawauchi in 1952, 183 men were killed. Some people believe the total number of deaths exceeded 200.

At the time, there were approximately 550 households in Kawauchi, which had a population of about 2,300. About 10 percent of the population was killed in the atomic bombing. There were about equal numbers of men and women, and 80 percent of the men were in their 40s or 50s.

Many families were left without their breadwinner. The wives of those who were killed repeatedly made the trip of more than 10 km into the city center and looked through stacks of bodies in search of their husbands. Many of them never found their husbands’ remains.

Days of hardship awaited them. They had no time to grieve. Pushing themselves, the women donned their husbands’ work clothes and went out into the fields that had been left to them, to survive and to feed their children.

They got up before dawn, loaded vegetables onto large two-wheeled carts and took them into town. Carrying pails, they went door to door collecting night soil in exchange for vegetables.

The women also turned out for day labor related to the rebuilding of the city. They received no aid from the government until 1953 when they became eligible for an annual payment of 3,000 yen in condolence money.

But they pulled together and carried on. In 1949 they formed the White Plum Society, a mutual aid organization. The society held sewing classes, and members went clam-digging together and encouraged each other. On the 6th of every month, they held a memorial service at Jogyoji, a local temple, and wept together.

Of the 19 women who were interviewed by Mr. Kanda, only one is still living: Masako Nomura, 92. “Those women made Kawauchi what it is today,” Mr. Kanda said. That history must not be forgotten.

Developments related to the Kawauchi area and the women who lost their husbands in the A-bombing

April 1889: Town of Kawauchi formed by merger of Nukui and Naka Joshi

March 1945: Volunteer Corps created through Cabinet resolution

May 1945: Hiroshima Prefecture directs municipalities to form volunteer corps

July 1945: Prefecture orders Kawauchi Volunteer Fighting Corps to participate in demolition of buildings in Hiroshima’s city center

August 1945: U.S. drops atomic bomb on Hiroshima

September 1945: Monthly memorial services at Jogyoji Temple begin; joint memorial service held in Kawauchi

May 1947: Constitution of Japan takes effect

February 1949: White Plum Society, a mutual aid organization for women of Kawauchi who lost their husbands in the war, formed

September 1949: Hiroshima Widows’ Association (now Hiroshima Single Parents and Children’s Welfare Association) formed

April 1952: Act on Relief of War Victims and Survivors enacted; families of Volunteer Fighting Corps members eligible for survivor condolence money

February 1953: White Plum Society erects monument to local war dead and other victims of the war on grounds of Kawauchi Elementary School

July 1955: Kawauchi, Midorii, Yagi merge to form Sato-cho

May 1958: Act on Relief of War Victims and Survivors revised; families of Volunteer Fighting Corps members eligible for survivor’s benefit

April 1963: Special Survivor Benefit Act for wives of war dead and others enacted; wives of Volunteer Fighting Corps members eligible for special survivor’s benefit

August 1964: Monument to Volunteer Fighting Corps erected in Peace Memorial Park

March 1973: Sato-cho merges with the City of Hiroshima

April 1980: Hiroshima becomes a “city designated by government ordinance”; with creation of wards, Kawauchi becomes part of Asa Minami Ward

February 1982: “I Lost My Husband to the A-Bomb” by Mikio Kanda published

February 1988: Hiroshima interchange of Sanyo Expressway opens in Kawauchi

October 1999: The Furukawa District, which includes Kawauchi, is created as part of city’s re-demarcation

October 2010: According to national census, population of Kawauchi area is 13,847, six times its February 1944 population of 2,375

Keywords

Volunteer Fighting Corps

In 1945, at the end of World War II, in anticipation of a decisive battle on the Japanese mainland, the government formed Volunteer Citizen Corps (later renamed the Volunteer Fighting Corps) in communities and at companies throughout the country. All civilian men aged 12 to 65 and women aged 12 to 45 were members. They engaged in the demolition of buildings and civil defense activities. According to an estimate by the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, a total of 11,633 members of Volunteer Fighting Corps from the city of Otake and other areas surrounding Hiroshima had been mobilized in the city on the day of the atomic bombing. Of these, 4,632 are believed to have been killed.

Government relief for survivors of Volunteer Fighting Corps members

Families of members of the Volunteer Fighting Corps who were killed became eligible for relief from the government with the passage of the Act on Relief of War Victims and Survivors in 1952. For 10 years starting in 1953 the national government paid annual survivor condolence money of 3,000 yen to the families of victims. With the revision of the relief act in 1958, members of the Volunteer Fighting Corps were classified as “paramilitary,” and their families became eligible for survivor benefits. Following this revision, annual survivor benefits of 25,500 yen were paid to the families of members of the Volunteer Fighting Corps, half the amount paid to the families of military personnel and civilian employees of the military. In 1963 the five-year limit on the payment of benefits was abolished. Starting in 1974, survivors of members of the military received the same amount as survivors of civilian employees, and payments were increased in stages in line with inflation. The current annual survivor’s benefit is just under 2 million yen. Since 1963 a special survivor benefit of 200,000 yen per year has also been paid to the wives of those who died in the war.

(Originally published on July 7, 2013)