Living in Kawauchi, “Town of the Atomic Bomb” [2-1]

Jul. 30, 2013

Part 2: Supporting each other

Article 1: Chinese cabbage

by Michiko Tanaka, Staff Writer

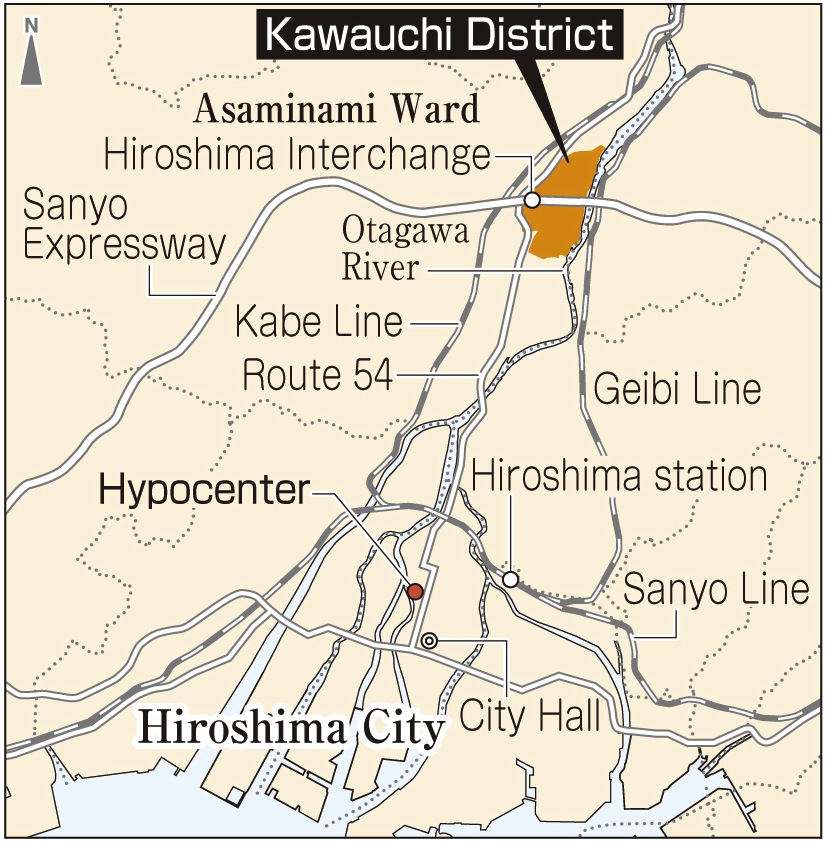

Source of postwar livelihood; boy’s struggles depicted in picture-card story

Sixty-eight years ago, all of the members of the Volunteer Fighting Corps from the small town of Kawauchi in Hiroshima Prefecture (now part of Asa Minami Ward), who numbered about 200, were killed near the hypocenter when the atomic bomb was dropped. The town’s women and children, who had suddenly been deprived of their breadwinners, supported and encouraged each other through the postwar years. The Chugoku Shimbun visited Kawauchi, which has gone from a farming village to a bedroom community, and looked at how the community’s history is being conveyed to the younger generation.

In mid-July, not long before summer vacation, 30 members of a fourth-grade class at Kawauchi Elementary School in Hiroshima’s Asa Minami Ward were absorbed in a picture-card show called “Hide and Chinese Cabbage.” It tells the story of a boy who lost both parents to the atomic bomb at the age of 13 and made a living by growing Chinese cabbage.

The story is based on the life of a real person, Hideso Itao, who died in 2010 at the age of 78. A teacher at Kawauchi Elementary School created the picture-card story in 2007 after hearing from Mr. Itao the story of his life. Mr. Itao’s wife, Miyuki, 78, who still resides in Kawauchi, recalls the day the teacher came to visit.

Little by little, her husband, who was a man of few words, began to tell his story. By then they had been married about 50 years, and, although she was familiar with her husband’s past, Miyuki found herself getting choked up. “I realized how hard he had struggled,” she said. “If it hadn’t been for the A-bomb, his life would have been different.”

On August 6, 1945, Mr. Itao’s father Kazuo, then 37, an Army medic, was in Kanon-cho (now part of Nishi Ward). His mother, Michi, 34, was in Nakajima Shin-machi (now part of Naka Ward), near the hypocenter, working on the demolition of buildings as a member of Kawauchi’s Volunteer Fighting Corps. Both of them were killed in the A-bombing.

Their children, four boys and a girl, were left to the care of their grandparents. The youngest boy was 2 years old at the time. The picture-card story depicts the struggles of Mr. Itao, who was the eldest son. Leaving home before dawn, he led a horse with a cart laden with vegetables to market. The yoke he used to carry the night soil he collected cut into his shoulders. “‘If I don’t do this, we can’t survive.’ Hideso kept going, using what little strength he had,” the story says.

Learning from his neighbors, he planted seeds: barley, millet, sweet potatoes, tomatoes. In the fall he planted Chinese cabbage. “Around the time I came here after marrying, people in Kawauchi began farming year-round. Everyone worked desperately hard just to survive,” Miyuki recalled.

In the Meiji Period (1868-1912) farmers in the Kawauchi area steadily improved their Chinese cabbage. Nestled between the Ota and Furukawa rivers, Kawauchi is blessed with soil with good drainage, making it well-suited for growing Chinese cabbage. Three years after the war ended, Kawauchi’s agricultural cooperative built a processing plant for pickles, and the number of producers of Chinese cabbage grew further. Women and children learned methods for boosting the harvest. They also earned extra money by helping with pickling in the winter, putting their chapped hands into cold water to wash the Chinese cabbage.

Mr. Itao, who had gained confidence in his farming, began to focus on Chinese cabbage. In 1959 he and some friends built a processing plant, and be began working in sales as well, making enough money to pay the school expenses of his younger brothers and sister. “My husband was passionate about Chinese cabbage,” Miyuki said. “It was an important source of income.”

After the war, Chinese cabbage provided a way for the people of Kawauchi, which is located 10 km north of the hypocenter, to support themselves, and it became a top winter crop. Meanwhile, spurred by Japan’s rapid economic growth after the war, more and more homes were built in Kawauchi. The Sanyo Expressway cut through the town’s fields, and the home of Chinese cabbage was transformed.

Since 1980 the area devoted to the growing of Chinese cabbage has dwindled from 57 hectares to 22 hectares today. Mr. Itao’s field, which is now only about 0.2 hectares, and his processing plant now belong to his son Hiroyuki, 51, a company employee, and his wife Tomoko, 48. “I never thought I’d take over the farm, but I can’t let go of the fields that my dad put his heart and soul into,” Hiroyuki said. He has begun to think about retiring early and devoting himself to farming.

The picture-card story ends with these lines: “Hiroshima’s Chinese cabbage became famous throughout Japan. We must not forget that this was thanks to the hard work and struggles of Hideso and others after the war.”

(Originally published on July 25, 2013)

Article 1: Chinese cabbage

by Michiko Tanaka, Staff Writer

Source of postwar livelihood; boy’s struggles depicted in picture-card story

Sixty-eight years ago, all of the members of the Volunteer Fighting Corps from the small town of Kawauchi in Hiroshima Prefecture (now part of Asa Minami Ward), who numbered about 200, were killed near the hypocenter when the atomic bomb was dropped. The town’s women and children, who had suddenly been deprived of their breadwinners, supported and encouraged each other through the postwar years. The Chugoku Shimbun visited Kawauchi, which has gone from a farming village to a bedroom community, and looked at how the community’s history is being conveyed to the younger generation.

In mid-July, not long before summer vacation, 30 members of a fourth-grade class at Kawauchi Elementary School in Hiroshima’s Asa Minami Ward were absorbed in a picture-card show called “Hide and Chinese Cabbage.” It tells the story of a boy who lost both parents to the atomic bomb at the age of 13 and made a living by growing Chinese cabbage.

The story is based on the life of a real person, Hideso Itao, who died in 2010 at the age of 78. A teacher at Kawauchi Elementary School created the picture-card story in 2007 after hearing from Mr. Itao the story of his life. Mr. Itao’s wife, Miyuki, 78, who still resides in Kawauchi, recalls the day the teacher came to visit.

Little by little, her husband, who was a man of few words, began to tell his story. By then they had been married about 50 years, and, although she was familiar with her husband’s past, Miyuki found herself getting choked up. “I realized how hard he had struggled,” she said. “If it hadn’t been for the A-bomb, his life would have been different.”

On August 6, 1945, Mr. Itao’s father Kazuo, then 37, an Army medic, was in Kanon-cho (now part of Nishi Ward). His mother, Michi, 34, was in Nakajima Shin-machi (now part of Naka Ward), near the hypocenter, working on the demolition of buildings as a member of Kawauchi’s Volunteer Fighting Corps. Both of them were killed in the A-bombing.

Their children, four boys and a girl, were left to the care of their grandparents. The youngest boy was 2 years old at the time. The picture-card story depicts the struggles of Mr. Itao, who was the eldest son. Leaving home before dawn, he led a horse with a cart laden with vegetables to market. The yoke he used to carry the night soil he collected cut into his shoulders. “‘If I don’t do this, we can’t survive.’ Hideso kept going, using what little strength he had,” the story says.

Learning from his neighbors, he planted seeds: barley, millet, sweet potatoes, tomatoes. In the fall he planted Chinese cabbage. “Around the time I came here after marrying, people in Kawauchi began farming year-round. Everyone worked desperately hard just to survive,” Miyuki recalled.

In the Meiji Period (1868-1912) farmers in the Kawauchi area steadily improved their Chinese cabbage. Nestled between the Ota and Furukawa rivers, Kawauchi is blessed with soil with good drainage, making it well-suited for growing Chinese cabbage. Three years after the war ended, Kawauchi’s agricultural cooperative built a processing plant for pickles, and the number of producers of Chinese cabbage grew further. Women and children learned methods for boosting the harvest. They also earned extra money by helping with pickling in the winter, putting their chapped hands into cold water to wash the Chinese cabbage.

Mr. Itao, who had gained confidence in his farming, began to focus on Chinese cabbage. In 1959 he and some friends built a processing plant, and be began working in sales as well, making enough money to pay the school expenses of his younger brothers and sister. “My husband was passionate about Chinese cabbage,” Miyuki said. “It was an important source of income.”

After the war, Chinese cabbage provided a way for the people of Kawauchi, which is located 10 km north of the hypocenter, to support themselves, and it became a top winter crop. Meanwhile, spurred by Japan’s rapid economic growth after the war, more and more homes were built in Kawauchi. The Sanyo Expressway cut through the town’s fields, and the home of Chinese cabbage was transformed.

Since 1980 the area devoted to the growing of Chinese cabbage has dwindled from 57 hectares to 22 hectares today. Mr. Itao’s field, which is now only about 0.2 hectares, and his processing plant now belong to his son Hiroyuki, 51, a company employee, and his wife Tomoko, 48. “I never thought I’d take over the farm, but I can’t let go of the fields that my dad put his heart and soul into,” Hiroyuki said. He has begun to think about retiring early and devoting himself to farming.

The picture-card story ends with these lines: “Hiroshima’s Chinese cabbage became famous throughout Japan. We must not forget that this was thanks to the hard work and struggles of Hideso and others after the war.”

(Originally published on July 25, 2013)