Daughter creates documentary film on second-generation Japanese-American who fought in World War II

Nov. 19, 2013

by Rie Nii, Staff Writer

Hiroshi Matsumoto, 100, is a second-generation Japanese-American living in the United States. His father Wakaji was from the city of Hatsukaichi in Hiroshima Prefecture. Hiroshi grew up going back and forth between the two nations of Japan and the United States, whose culture and customs were radically different. During World War II, he fought against Japanese forces and happened to come across his younger brother and cousin housed at POW camps in China. Karen Matsumoto, 59, Hiroshi’s second daughter and also a U.S. resident, has captured the story of his turbulent life in a 28-minute documentary film, made in English.

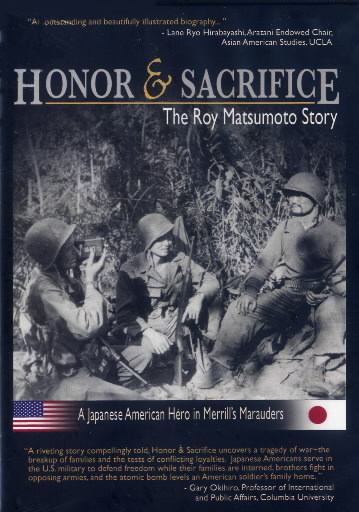

The film is entitled “Honor and Sacrifice.” It features interviews with Hiroshi and photographs that Wakaji took in California and Hiroshima. Wakaji learned photography in the United States before the war, and ran a photo studio in Hiroshima after returning to Japan.

Hiroshi was born in the suburbs of Los Angeles in 1913. In 1921, he came back to Hiroshima. In 1927, his family, including Wakaji, also returned to Japan. But Hiroshi could not adapt to Japanese customs, and his mother Tei told him to go back to the United States. In 1930, Hiroshi returned to the United States by himself, relying on his uncle in the United States for support.

At the outbreak of the war, Hiroshi was taken to an internment camp for Japanese-Americans. When an officer from the U.S. Military Intelligence Service (MIS) came to his camp in search of detainees with a good command of Japanese, he volunteered for duty out of the sheer desire to leave the camp. At the MIS, Hiroshi joined a guerrilla unit. In 1943, he went to Myanmar, formerly Burma, as part of Merrill’s Marauders, a special operations unit involved in jungle warfare. Amid dangerous conditions, he tapped telephone wires of the Japanese military and disturbed the operations of Japanese forces with his fluent Japanese.

Hiroshi learned about the atomic bombing of Hiroshima while working in China, where he interrogated Japanese prisoners, following his service in Myanmar. At the time he assumed his entire family, including his father, who had run a photo studio near the major intersection in the Kamiya-cho district (now, part of Naka Ward), perished in the blast. However, by chance he came across his cousin, who was being detained at a POW camp in Shanghai, and learned that his family had moved to the city of Hatsukaichi and had survived the bombing. He was also reunited with a younger brother, Isao, who was at another POW camp in Shanghai, and they talked for a few hours about their family.

In 1983, Karen became aware of her father’s activities in Myanmar. When she was 30 years old, a professor at her graduate school handed her a book about Merrill’s Marauders. Partly because the MIS operations had been classified for 50 years, it was not until 2008, when she began to create the documentary, that she learned the details of what occurred there.

In addition, a large number of photographs taken by Wakaji were discovered at his house in the city of Hatsukaichi, which boosted Karen’s efforts to make the film. Karen’s motivation for pursuing this project stems from her desire to make the role that Japanese-Americans played during World War II more widely known. She also indicated that the film conveys her message against war, which forces scores of people into sacrifices.

The film was awarded the Jury’s Best Short Documentary prize at the Townsend Film Festival, held in September in Port Townsend, Washington. The film is now being shown across the United States.

Karen would like children, in particular, to see the film. She also hopes that Japanese subtitles can be created. Hiroshi shared his wish that the film will raise awareness of the role of second-generation Japanese-Americans who served in the MIS during the war. It was work he had to carry out to survive, he added.

A DVD of the film can be viewed in the library at Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

(Originally published on November 4, 2013)

Hiroshi Matsumoto, 100, is a second-generation Japanese-American living in the United States. His father Wakaji was from the city of Hatsukaichi in Hiroshima Prefecture. Hiroshi grew up going back and forth between the two nations of Japan and the United States, whose culture and customs were radically different. During World War II, he fought against Japanese forces and happened to come across his younger brother and cousin housed at POW camps in China. Karen Matsumoto, 59, Hiroshi’s second daughter and also a U.S. resident, has captured the story of his turbulent life in a 28-minute documentary film, made in English.

The film is entitled “Honor and Sacrifice.” It features interviews with Hiroshi and photographs that Wakaji took in California and Hiroshima. Wakaji learned photography in the United States before the war, and ran a photo studio in Hiroshima after returning to Japan.

Hiroshi was born in the suburbs of Los Angeles in 1913. In 1921, he came back to Hiroshima. In 1927, his family, including Wakaji, also returned to Japan. But Hiroshi could not adapt to Japanese customs, and his mother Tei told him to go back to the United States. In 1930, Hiroshi returned to the United States by himself, relying on his uncle in the United States for support.

At the outbreak of the war, Hiroshi was taken to an internment camp for Japanese-Americans. When an officer from the U.S. Military Intelligence Service (MIS) came to his camp in search of detainees with a good command of Japanese, he volunteered for duty out of the sheer desire to leave the camp. At the MIS, Hiroshi joined a guerrilla unit. In 1943, he went to Myanmar, formerly Burma, as part of Merrill’s Marauders, a special operations unit involved in jungle warfare. Amid dangerous conditions, he tapped telephone wires of the Japanese military and disturbed the operations of Japanese forces with his fluent Japanese.

Hiroshi learned about the atomic bombing of Hiroshima while working in China, where he interrogated Japanese prisoners, following his service in Myanmar. At the time he assumed his entire family, including his father, who had run a photo studio near the major intersection in the Kamiya-cho district (now, part of Naka Ward), perished in the blast. However, by chance he came across his cousin, who was being detained at a POW camp in Shanghai, and learned that his family had moved to the city of Hatsukaichi and had survived the bombing. He was also reunited with a younger brother, Isao, who was at another POW camp in Shanghai, and they talked for a few hours about their family.

In 1983, Karen became aware of her father’s activities in Myanmar. When she was 30 years old, a professor at her graduate school handed her a book about Merrill’s Marauders. Partly because the MIS operations had been classified for 50 years, it was not until 2008, when she began to create the documentary, that she learned the details of what occurred there.

In addition, a large number of photographs taken by Wakaji were discovered at his house in the city of Hatsukaichi, which boosted Karen’s efforts to make the film. Karen’s motivation for pursuing this project stems from her desire to make the role that Japanese-Americans played during World War II more widely known. She also indicated that the film conveys her message against war, which forces scores of people into sacrifices.

The film was awarded the Jury’s Best Short Documentary prize at the Townsend Film Festival, held in September in Port Townsend, Washington. The film is now being shown across the United States.

Karen would like children, in particular, to see the film. She also hopes that Japanese subtitles can be created. Hiroshi shared his wish that the film will raise awareness of the role of second-generation Japanese-Americans who served in the MIS during the war. It was work he had to carry out to survive, he added.

A DVD of the film can be viewed in the library at Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

(Originally published on November 4, 2013)