"Transmitting the Experiences of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to Future Generations": International symposium examines path to a world without war or nuclear weapons

Jan. 21, 2014

An international symposium entitled “Transmitting the Experiences of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to Future Generations” was held on December 7 at the International Conference Center Hiroshima in Naka Ward. A panel including three representatives of museums in Rwanda, Cambodia and Poland that tell stories of genocide, discussed educational programs to hand down memories of calamities, including the atomic bombings, to the next generation and the importance of preserving the accounts of survivors. There were also reports from Hiroshima and Nagasaki by the director of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum; a college student from the Nagasaki Youth Delegation who traveled to Geneva, Switzerland last spring; junior writers for the Chugoku Shimbun; and the vice president of the Hiroshima Peace Institute at Hiroshima City University. Approximately 430 people attended the symposium, which was jointly sponsored by Hiroshima City University, the Nagasaki University Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition, and the Chugoku Shimbun.

◆Keynote speech (delivered by proxy)

Atsuko Hayakawa, 53, professor, Tsuda College

◆Panelists from overseas

Yves Kamuronsi, 32, deputy director, Kigali Genocide Memorial Center (Rwanda)

Takeshi Nakatani, 47, official guide, Auschwitz National Museum (Poland)

Sophearum Chey, 32, vice chief, Tuol Sleng Museum of Genocide (Cambodia)

◆Presenters of reports

Kenji Shiga, 61, director, Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

Keiko Nakamura, 41, associate professor, Nagasaki University Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition

Anna Shimoda, 21, member, Nagasaki Youth Delegation

Kazumi Mizumoto, 56, vice president, Hiroshima Peace Institute, Hiroshima City University

Akira Tashiro, 66, executive director, Chugoku Shimbun Hiroshima Peace Media Center

Kantaro Matsuo, 15, junior writer

Yumi Kimura, 17, junior writer

◆Moderators

Robert Jacobs, 53, associate professor, Hiroshima Peace Institute

Hitoshi Nagai, 48, associate professor, Hiroshima Peace Institute

Educational Programs

Understanding of background essential: Kamuronsi

Conducting tours using survivors’ words: Nakatani

Moderator: Many references have been made to the importance of education. What sorts of things are you doing, and what challenges do you face?

Kamuronsi: We have children of survivors and perpetrators of genocide studying in the same classrooms. It’s important for both groups to build a cooperative relationship. It’s not a matter of feeling responsible for what their parents’ generation did. It’s more important to understand the background behind what happened, including the propaganda – things like how their parents’ generation became involved and why the genocide occurred.

Chey: We conduct an educational program for students in which they interview their parents and grandparents about their experiences of the genocide. They have a dialogue among the family and record it.

The victims and perpetrators of the genocide will pass away eventually. Someday people will want to know the truth about what happened, so we want to preserve at our museum the accounts of their families’ experiences that the students gather.

Some people say that the younger generation doesn’t have a clear understanding of the genocide that took place in their country. We have to make sure that 50 or 100 years from now there won’t be people who want to return to the ideology of the Khmer Rouge, who carried out the genocide.

Mizumoto: I teach peace studies at Hiroshima City University. Even students who grew up in Hiroshima learning about the atomic bombing and peace aren’t aware of certain information, and we must provide it to them. I’m always trying to dig up stories that have been lost and get my students interested in them.

Nakatani: I’m not a Holocaust survivor, so when I give people tours I feel the stories of survivors are especially important. When I started giving tours 15 years ago, I sometimes gave tours to survivors, and I have modeled my gestures on theirs. I still can’t talk about the Holocaust in my own words. I mention certain survivors by name and recount what they said. I speak on their behalf.

Moderator: It can be traumatic to learn about distressing events at a young age. At what age do you start your educational programs and what sort of education is it?

Kamuronsi: You have to be careful when telling things to small children. When children ask what genocide is, how do you define it? Sometimes the bodies of relatives are found, and then there has to be some explanation what happened. I haven’t found the answer yet. I try to explain the background behind what happened through pictures and stories.

Nakatani: Our stance is that children should be at least 14 years old before they visit our museum because by that age they have developed a certain amount if cognitive ability. When I give tours to Japanese kids who are younger than that, I tell their parents about our policy. In many cases, children can properly understand the displays if they’ve prepared beforehand.

Learning from other countries

Gain a deeper understanding by analyzing causes: Mizumoto

Moderator: What do you feel about the significance and importance of teaching about genocide that has occurred in other countries?

Chey: It’s important to learn about the background behind the atomic bombings and genocide as well and to consider what happened. The backgrounds of each may differ, but the suffering is the same. We must cooperate, learn about these things together and then convey what we’ve learned to the next generation with a clear sense that the same thing must never happen again.

Kamuronsi: It’s important to learn from what has happened in other countries when considering how we can prevent genocide and war. The fact that there are still wars going on today shows that the lessons of the past haven’t been learned. That’s why it’s important to expand our knowledge.

Nakatani: We need to look at Auschwitz as something that could happen in any country in any age.

Mizumoto: It’s important to learn about the calamities have occurred in many areas and to analyze their causes. We have to learn what brought about the collapse of peace, leading to conflict, violence and killing among people who had lived together peacefully. If we do that, we can go beyond considering just the fact that a nuclear weapon, the ultimate form of violence, was used on Hiroshima.

Moderator: Do you teach about the prejudice and discrimination that lie behind genocide?

Mizumoto: Japan is an island nation, and compared to the continent it has had fewer opportunities for direct contact with other cultures. So I make a conscious effort to teach about Islam, Hinduism and the cultures of regions far removed from life in Japan. Japanese people tend to exclude people of other cultures when they don’t understand something. This can lead to violence. I try to get my students to understand that people may be different but we are all the same human beings.

Nakatani: There’s a big difference between Europeans and Japanese people in terms of the awareness of racial discrimination. In Europe people don’t say racist things in public, whereas in Japan there seems to be a sense that a certain amount of racism is no big deal. When the news media notice this sort of thing, they should speak out against it. Japan is too lenient when it comes to racism.

Message to young people

Calamities must not be forgotten: Chey

Moderator: We’d like to hear about the messages you are trying to convey to the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, particularly to young people.

Kamuronsi: I’d like to tell the young people of Rwanda, who are the future of the nation, about Hiroshima. I’d also like the young people of Hiroshima to tell their friends and families about the genocide in Rwanda and the efforts toward reconciliation. The young people of Rwanda and Hiroshima and the rest of Japan need to be able to relate to each other and get to know each other.

Nakatani: I’m glad to see quite a few young people here today. Young people are flexible and sensitive, and they have the courage to face whatever hardships they may encounter. Society needs young people like that, and I’d like them to work hard for the good of society.

Chey: On this visit to Hiroshima I’ve been able to learn a lot about the atomic bombing, and I’ve been able to talk with you at this symposium. I’ve been particularly impressed by the young people of Hiroshima. I want to convey Hiroshima’s message to the young people of Cambodia. I’d like to contribute to building peaceful relations among families, classmates and neighbors. We must not forget the catastrophes we have experienced.

Mizumoto: When passing on memories to the younger generation there’s a tendency to feel that everything must be handed down as knowledge. But that’s not the case. It’s important not only to pass on knowledge but also to give young people knowledge of how to avoid repeating these tragedies, after fully examining their inhumanity.

Yves Kamuronsi

My name is Yves Kamuronsi. I am the deputy director of the Kigali Genocide Memorial Centre, where I have been working since 2004.

I survived the genocide in Rwanda when I was 13 years old. I lost both my parents, my elder brother, my aunts, my cousins, my grandfather, and other members of my extended family.

I survived with my two sisters. At the time, one was 12 and the other was 9.

Today I am honored to be here at this conference, sharing with you the history of genocide in Rwanda and how Rwanda is preserving the memory of this tragedy for future generations and what is being done to rebuild the country.

My presentation is divided into three main parts.

Part 1

I will start my presentation by giving the historical background behind the genocide in Rwanda. I will then talk about what happened during this time, which I will call the 100 days of Genocide.

Part 2

In this part of my presentation, I will talk about the consequences of the genocide and how Rwanda has been able to cope.

Part 3

I will discuss the work of the Kigali Genocide Memorial Centre and briefly talk about various projects that are being developed at the Centre. This will include documenting and preserving the memory of the genocide and peace-building education, which is part of the recovery process.

"During my presentation I will use images to help illustrate the context."

Slide 1

Rwanda before genocide:

• 3 "ethnic" groups in Rwanda (Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa) living in harmony: categorised by social status.

• The polarisation between Hutu and Tutsi as a result of the change from social to ethnic categories began and progressively grew worse since the colonial era: Germany 1896-1916; Belgium 1916-1962.

• The policy of ‘divide and rule’ gradually built up resentment and a culture of hatred among the Hutu toward the Tutsi.

Slide 2

Genocide in Rwanda began in 1959:

• Dehumanization campaign: culminated in the first attempt of Tutsi ethnic cleansing with more than 20,000 Tutsi killed in 1959.

• Tutsi were forced to flee the country: important groups fled to Uganda, Burundi, Congo, and Tanzania.

• Development of exclusion policies and structures meant to nourish hate toward the Tutsi: education, employment, etc.

• Radio, the main media source in Rwanda, was also used to spread propaganda up until the execution of genocide in 1994.

Slide 3

100 Days of Genocide:

Genocide began on April 7, 1994.

More than 1,000,000 Tutsi were killed in the space of 100 days with the strategy of leaving none to tell the story (proven by Alison de Forges, U.S. human rights activist).

The killings occurred across the country.

Militias were trained to use all kinds of weapons and instruments to kill and inflict atrocities on Tutsis and their so-called Hutu allies: machetes, clubs, stoning, guns, rape, torture.

Slide 4

Consequences of genocide:

More than 120,000 children were orphaned.

100,000 widows and widowers. 75% of these survivors were infected by HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases.

Women developed cancer and other complications from their untreated wounds.

80% of survivors experience severe post-traumatic stress.

Slide 5

What marked the genocide in Rwanda:

• Speed of the violence: More than 1 million people killed within a period of less than 100 days.

• Efforts to totally annihilate the targeted people (Leave None to Tell the Story): criteria to select victims from perpetrators (9/10 Tutsi targeted killed, not one single targeted family which remained was unaffected by the genocide).

• Mass participation: Mass participation (1.05 million victims and more than 1.2 million perpetrators).

• Multiple and extreme forms of cruelty: systematic rape, hacking with machetes, burying victims alive, burning with fire, etc.).

• Victims overwhelmed by what was happening (normal life during genocide had stopped).

Slide 6

Challenges in Rwanda after 100 days of genocide:

Desolation of the population.

Compromised unity and social cohesion.

The image of Rwanda was tarnished abroad.

All the country’s key sectors were destroyed :

- Justice

- Economy

- Health

- Education

Question: How to preserve this memory while reconciling?

Slide 7

Justice:

More than 120,000 detainees accused of genocide crimes.

Gacaca court established, using a traditional form of justice. If the normal court system has been used, the process would have taken around 100 years.

Most people convicted in Category 3 and 2 have served their sentences and are now back in communities.

The Gacaca courts completed their work in 2012, after 10 years. They tried around 2 million cases.

Slide 7

Memory preservation:

• 8 genocide sites are being preserved at the national level as memorials.

• 30 sites are being preserved at the district level through Rwanda.

• 461 genocide sites are being preserved at the grassroots level.

Now I will discuss how “memory” is being used in Rwanda to teach the younger generation and aid peace-building.

In my presentation I will use the ‘’Kigali Genocide Memorial Centre’’ as a model.

Slide 8

Kigali Genocide Memorial:

• Located in Kigali, it is the nation’s most-visited memorial, inaugurated in 2004, on the 10th anniversary of the Tutsi genocide. It was created through a joint partnership of the Kigali City Council and the UK-based NGO, Aegis Trust.

• A place for survivors to bury their loved ones in dignity. Today more than 258,000 victims of genocide from Kigali are buried in 14 mass graves.

Slide 9

The Kigali Genocide Memorial Centre has 4 main parts:

• Graves and Memorial Gardens

• Exhibition

• Education Program

• Archive and Documentation

Slide 10

Exhibitions:

Three permanent exhibitions:

1. History about the genocide in Rwanda.

2. An exhibition about child victims of genocide.

3. History of other genocides around the world.

The main exhibition uses oral history testimonies, artifacts, human remains, and panels.

Slide 11

Education program:

Purpose of the education program:

• A response to genocide ideology in schools (anonymous letters to the surviving students, throwing their books, hatred messages in classrooms and bathrooms.)

• Building peace in the post-genocide society

• Positive understanding of identity and ethnicity

• Building trust and responsibility among young Rwandans

• Learning lessons from the past

Slides 12

Education program is attended by:

School students ranging in age from 12-20 years

Teachers in history and civic education

Community leaders

Slide 13

Main topics and content of the on-site education:

• Ideology of genocide

• Propaganda

• Difference between genocide and war

• The Holocaust and other cases of genocide

• Allaying the guilt of students who come from the families of survivors and perpetrators

• Critical thinking and problem solving

• Group discussions

Slide 14

Group discussion:

Discuss the following questions:

• What does “Never again” mean to you?

• Do my actions affect other people’s lives?

• As an individual, can I make a difference?

• What ways were used by the Nazis to discriminate against Jews?

• How much responsibility do you think the international community has for the genocide in Rwanda?

• What role do young people have in the process of peace building in Rwanda?

Slide 15

Peace building:

Mobile exhibition and educational workshops as a way forward:

• 2,500,000 Students in Rwanda

• Only 11,000 Students have attended our workshops at Kigali Genocide Memorial

• Transportation is a problem

• Targeting local community and teachers

• Using 3 testimonies and peace-building stories

Slide 16

Main objectives of peace building:

• Using a storytelling approach to educate as a form of best practice

• Sharing successful stories of peace initiatives around the country to stimulate discussions and debates about unity and reconciliation

• Developing critical thinking skills and promoting sustainable peace among youth and communities

• Presenting and discussing the role of youth in building a sustainable peace

Slide 17

Mobile exhibition content:

• Introduction to Rwandan history

• Selected peace-making stories from around the country

• Is the journey to peace possible?

• Children’s stories

Slide 18

Archive and documentation:

• 200 Survivors testimonies have been recorded

• 100 Remembrance and Exhumation ceremonies have been filmed

• 700 audiovisual tapes for Gacaca courts have been filmed, each 30 minutes

• 50 rescuers’ stories have been recorded: these are the stories of people who risked their lives to save others

Slide 19

Documentation of victims:

38,000 names of the victims collected

Around 5,000 pictures and other artifacts of the genocide victims are available in the archive

Slide 20

Genocide mapping:

A project of genocide mapping, using a GPS device, has been initiated to chart the detail of the genocide geographically. About 1000 roadblocks and 850 mass graves have been identified.

Slide 21

Purpose of Archive and Documentation Center:

• To create a permanent center for documentation to raise awareness of the atrocities that took place and to help those researching them.

• International genocide resource: Provide online access and work to help researchers and scholars worldwide.

• To produce both a physical and online documentation centre. Combined, these will provide a worldwide research tool on the genocide in Rwanda for academics, students, and independent researchers.

• A research centre and research library for students and academics in Rwanda, while also serving as a portal for Rwandan scholars to publicize their findings on the genocide to the rest of the world.

Slide 22

After almost 19 years, continuing the journey of recovery by:

• Achieving social cohesion through peace-building programs that reach out to Rwandan communities, the East African region, and beyond

• Focusing on healing the society from trauma

• Further development of educational programs, outreach programs, preserving memory through documentation, archiving, and exhibitions

• Making Rwanda a role model using lessons learned from the genocide

Conclusion

Next year Rwanda will commemorate 20 years since the genocide and the theme is Memory in Action.

In Rwanda today we are learning from the past to build a better future.

I also believe that is the reason we are all here: to learn, to acknowledge what happened here and around the world, hoping that the lessons learned will serve to build a better place for our children and also give dignity to the victims.

Thank you !

Takeshi Nakatani

Good afternoon. My name is Takeshi Nakatani and I live in Poland. I serve as a Japanese-speaking guide at the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, a memorial and museum which includes the German concentration camps Auschwitz I and Auschwitz II-Birkenau. I’ve come to Hiroshima to share with you how Europe is handing down the holocaust, an enormous 20th century tragedy, to future generations.

First, I’ll show a series of slides and explain what happened in Auschwitz. This will take about five minutes.

[Slide 1]

After Nazi Germany invaded Poland, located in eastern Europe, and ignited World War II, it built the Auschwitz I concentration camp here.

[Slide 2]

In the beginning, the camp was intended to house Polish political prisoners.

[Slide 3]

As there were Polish army barracks, these barracks were used to house prisoners.

[Slide 4]

When the Auschwitz concentration camp was filled to capacity, Nazi Germany began constructing the second camp, Auschwitz II-Birkenau.

[Slide 5]

Following the “Final Solution” decision, large numbers of Jews were taken to Auschwitz from across Europe. The Nazis then built gas chambers. This is a blueprint of a gas chamber.

[Slide 6]

This is the exterior of a gas chamber, which also held an incinerator. Smoke from cremations of the dead rose from this chimney.

[Slide 7]

This is a window to gaze into a gas chamber.

[Slide 8]

These cylindrical containers held granules of gas known as Zyklon B.

[Slide 9]

These granules emitted the poison gas. In all, about one million people were put to death in this fashion.

[Side 10]

When they withdrew from Auschwitz, the Nazis wrecked the gas chambers to destroy evidence of their deeds.

[Slide 11]

In Poland, the temperature falls to minus 20 degrees Celsius in winter.

[Slide 12]

About 400 people were housed in a stable built for 52 horses.

[Slide 13]

These prisoners were kept alive for a few months and forced to engage in hard labor.

[Slide 14]

The Nazis also set fire to the barracks to destroy evidence.

[Slide 15]

The Nazis killed up to several thousand Jews a day. At times, the bodies were cremated in the fields.

[Slide 16]

The Nazis forced other Jews to undertake this work.

[Slide 17]

These photos were secretly taken by a Jew.

[Slide 18]

Members of the Nazi SS were volunteers with clearly no sense of guilt.

[Slide 19]

This is Heinrich Himmler of the SS and Rudolf Höss, the commandant of the Auschwitz concentration camp, with executive officers of a major German corporation. To the world’s horror, the extermination of the Jews was a grand national policy.

----------------Slides end here----------------

It was decided that, after the war, the liberated nations would assume control of the former sites of the German concentration camps. In 1947, Poland opened the Auschwitz-Birkenau site to the public as a national memorial museum with survivors of the holocaust serving as director and staff. It was difficult, apparently, to run the museum in socialist Poland, where the Soviet Union held sway. Free speech was curtailed by Polish officials and anti-Semitic policies lingered after the war.

However, with the end of the Cold War in 1989, Poland not only moved to create ties with Western Europe, it engaged in dialogue with Jewish intellectuals. The push now began to renew perceptions of Auschwitz, an effort still under way.

Since that time, Poland has stressed the fact that a score of people, mainly Jews whose numbers rose to more than one million, as well as many other women and children, fell prey to the holocaust. Of course, we must not forget the many other victims of this tragedy, too, which include Polish citizens, Roma people, Soviet soldiers, political prisoners of various nationalities, the mentally- and physically-disabled, gays, lesbians, and members of the Jehovah’s Witnesses.

In 2004, Poland joined the European Union (EU). The EU, now comprised of 28 nations, views the holocaust as a lesson for the peaceful coexistence of different ethnic groups. Educational professionals within the EU gather on a regular basis to work together on handing down history to the next generation.

These efforts have begun to pay off.

[Photo 1]

This is the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. It draws so many visitors these days that at times we must limit admissions.

[Graph 1]

Visitors to the museum have tripled over the past ten years. The number of annual visitors is approaching 1.5 million.

[Table 1]

In 2012, 30 percent of visitors were from Poland, followed by visitors from the U.K., the U.S., and Italy. We receive many German visitors, too. The number of Japanese visitors totaled 13,000 that year, while there were 46,500 visitors from Korea.

[Table 2]

Young people aged 25 and under make up 72 percent of all visitors as a result of peace education policies in Europe.

With its population aging due to the low birthrate, coexisting with immigrants is a large challenge for European nations. It is important to look historically and learn about potential outcomes under such conditions. The EU has expanded in order to strengthen the economy and security of its member nations. Along with this expansion, the people of the EU believe that the first step in preventing a recurrence of genocide, epitomized by the holocaust, involves education and the development of a shared sentiment for confronting prejudice and discrimination.

The Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum is the ground of the holocaust. Visitors can feel and reflect on many things as they gaze at artifacts left by the victims, touch the buildings that were used at the time, and walk around the site. The contents of the exhibition, which were planned by survivors and continue to be widely admired, were chosen to mourn the victims and instruct the living so that human beings will never repeat such a tragedy.

Preservation is a key challenge for the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. In particular, the buildings which stand on Birkenau wetlands, made of brick and wood, are aging. In response, the Auschwitz-Birkenau Foundation was established in 2009, and the U.S. and European nations have pledged financial aid of roughly 100 million euros to date. The museum plans to invest these funds and allocate 500 million yen a year toward repairing these buildings.

Another problem involves the aging number of holocaust survivors, as each year there are fewer people able to offer their testimonies. The museum archives continues to record the survivors’ experiences for posterity. In the past, many survivors served as guides at the museum, but today, none of the more than 300 guides have direct experience of the war.

I have been serving as a guide there for 15 years. Initially, some executive members of the museum were reluctant to hire someone from Asia to take this role. But now they recognize that I can convey the holocaust to the Japanese people in clear terms. My interest is in how Europe, which has experienced a history of hardship, views and conveys this past to others.

In addition to the issue of coexistence with an immigrant population, Europe has been suffering its most serious recession since the 1930s. In Greece and Spain, the unemployment rate for youth is 50 to 60 percent. It is an especially important time to learn lessons from the past.

Hitler rose to power as a result of a democratic election. From a political point of view, there were a number of nations, including Japan, that were similar to Nazi Germany. Some people, even in Nazi-occupied nations, cooperated with the Nazis in exterminating the Jews. Against this backdrop, complete responsibility cannot be laid at the feet of Hitler and Germany, the nation that elected him.

In addition, the majority of Europeans at the time simply looked on as these events unfolded, and not all of them were German. These bystanders not only acquiesced to the violence involved in eliminating others based on race, they ultimately enabled this violence.

So what can the Japanese learn from the holocaust?

Sixty-eight years after the war, I believe that we should reflect not only on the tragedy itself that took place in Europe, but also on the historical background that led to the holocaust and has impacted our modern times. There remains significant prejudice and discrimination in Japanese society, too, and we also suffer from economic downturns. The holocaust is a time in history that exemplifies the fragile side of democracy.

As I routinely observe how European history is conveyed, I think about the significance of sharing this history with the Japanese people. One of Japan’s biggest challenges, along with its unsteady political ties with China and South Korea, is the nation’s declining birthrate. Though the Japanese economy has remained stable, thanks to the relative wealth of the elderly, in the future Japan will come to face a social environment similar to that of Europe.

In such an environment, it is vital that all of us recognize the failures of the past so that we create a more harmonious present in which to live. In this respect, I believe we can learn much from Europe’s experience.

I encourage you to look closely, from the outside, at European ways of handing down history and its significance to our time.

Thank you for your kind attention.

Chey Sophearum

[Introduction]

A. Brief self-introduction

My name is Chey Sophearum I was born in 1981. I have one sister and three brothers.

I finished my high school studies in 1999.

From 2002-2006, I earned a Bachelor’s degree of Education in English.

From 2006-2008, I earned a Master’s degree of Social Science and Law, specializing in Public Administration.

From 2003-2005, I worked as a volunteer at the Documentation Center of Cambodia, researching the history of the Khmer Rouge.

I got married in 2004 and now have two sons and one daughter.

In 2006, I joined the staff of the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum as a museum guide.

In 2008, I became Vice Chief of the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, responsible for our outreach program.

B. Brief history of the tragedy that occurred in Cambodia

The years 1975-1979 were a dark period in Cambodia, known then as Democratic Kampuchea.

The Khmer Rouge leaders were cruel killers who plunged the nation into a holocaust, with nearly three million people losing their lives because of overwork, starvation, and illness. While the Khmer Rouge leaders talked about human rights, none actually existed. Even today some Cambodians remain traumatized because of the Khmer Rouge regime.

C. Brief history of Tuol Sleng Museum

Security Office 21, one of the prisons and killing sites of the Khmer Rouge, was created on order of Pol Pot (former name, Sar Lot Sar), and was used from 1975 to January 6, 1979. The facility was called S-21 and was designed for detention, interrogation, inhuman torture, and killing after extracting “confessions” from the victims.

After the liberation of the Cambodian people from the genocidal regime on January 7, 1979, the government of the People’s Republic of Cambodia collected evidence from S-21, including photographs, filmed prisoner “confessions,” torture tools, shackles, and fourteen bodies. Such evidence of the criminal regime is now on display for Cambodian and international visitors.

Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum (formerly, Security Office 21) opened on August 19, 1979 when the Kampuchea People’s Tribunal prosecuted the Democratic Kampuchea leaders Pol Pot, Ieng Sary, and Khiev Samporn. The grounds of S-21 covered an area of 600 x 400 meters, and were surrounded by an iron fence that had been topped with barbed wire. Previously, these were the grounds of Tuol Sleng Primary School and Tuol Svay Pray High School. After its conversion to S-21, another iron fence topped with barbed wire was erected to encircle the site. The prison was made after Pol Pot’s regime forced city dwellers to leave their homes and to live in the remote countryside in conditions close to slavery.

The four buildings that had been used for the high school became a prison of tiny cells (0.8 x 2 meters), which held individual prisoners. The front of each building was covered in a fishnet of barbed wire to prevent prisoners from hurling themselves off and committing suicide.

When the Pol Pot regime collapsed, the Cambodian people undertook a variety of efforts to prevent genocide from occurring again in Cambodia.

[Activities and goal of Tuol Sleng Museum]

A. What aspects of this tragedy are central to what is being commemorated?

After Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum was opened for visitors from Cambodia and other nations, the government launched a country-wide effort to investigate the genocide. Information from people who were affected by the Pol Pot regime was gathered and these documents were stored at the museum. The aim was to convey the Khmer Rouge genocide clearly to the next generation. The exhibit on S-21 is one way for people to learn whether loved ones had been detained at this facility. During the time of the Democratic Kampuchea regime, people had no access to such information.

B. What are the short-term and long-term goals of Tuol Sleng Museum? What strageties are being used to accomplish these goals?

Short-term goals

Today, the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum is pursuing these activities:

Restoration work involves cleaning documents and holding them in boxes, then scanning them to create digital archives.

The museum has two exhibitions: one is the permanent exhibition, the other is the curriculum exhibition. The permanent exhibition provides detailed information on S-21, while the curriculum exhibition displays select artifacts and changes every two or three months.

Our mobile museum travels around the country to show curriculum exhibitions to high school students to help them understand the work of the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum.

The Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum has maintained an exchange of exhibitions and staff training with the Okinawa Peace Museum each year since 2009. Today, some countries request materials from the museum to be exhibited abroad.

When students from abroad, who are writing a thesis about genocide or tourism, come to Cambodia, we provide them with needed information and documents.

Some state and private high schools have brought their students to the Tuol Sleng Museum to learn about the past and the museum provides these groups with guides.

The Extraordinary Chambers in the Court of Cambodia (ECCC) brings people from around the country to the Tuol Sleng Museum twice a week, about 300 to 500 people at a time. The museum also provides ECCC documents necessary to render judgment on the leaders of the Khmer Rouge regime, such as Kang Kech Iev, called Duch.

Some Cambodian people who have visited Tuol Sleng Museum have discovered photographs of loved ones in the permanent exhibition. At their request, the museum provides them with black and white copies of these photographs.

After the Tuol Sleng Museum archives became part of the Memory of the World Register in 2009, the museum has had UNESCO support to protect the archives and maintain these aspects of the facility:

- Information room

- Air-conditioners

- Database group

- Car park

- Computers

- Renovating the document room: repainting and installing new windows and glass doors. - Renovating the ceiling of the central office roof.

Long-term goals

In the future the museum plans to expand its outreach program and construct a new building.

1. The outreach program will enable younger generations to learn about the Khmer Rouge regime and the S-21 prison. The program will bring 30 students to the museum each week, every Saturday morning, and receive a guided tour.

- 7:00 am Students arrive

- 7:30 am to 8:00 am Registration

- 8:00 am to 9:00 am Guided tour through the museum

- 9:00 am to 9:30 am Talks by survivors

- 9:30 am to 10:00 am Question & answer time

2. The Tuol Sleng buildings were constructed in 1963 and are now aging. A new building is needed for staff and for preserving documents.

To realize these two programs, support is needed.

C. What obstacles have you identified that must be overcome to make these strategies succeed?

- Before a proposal is pursued, the museum selects staff with the proper experience and educational background.

- The project team brainstorms together.

- Each proposal is analyzed for 6-7 months.

- Donors are sought.

The museum has a number of staff and programs, but partnerships are needed for training to develop the level of staff skills. Human resources are a vital aspect of the museum’s work.

Atsuko Hayakawa

Let me first of all express my profound gratitude to the organizers of this wonderful symposium for the invitation to this very important place of historic memory. Born in the post-war generation without having any direct experience of war, I owe much of my understanding of the world and humanity to Hiroshima, the place where the unspeakable tragedy has been consciously maintained as human legacy. To be honest, I have few words to express its importance. However, as a translator whose task it is to translate those words of wishes, aspirations and sometimes painful feelings of the people of the past into the language of others beyond time and space, and as an academic with the responsibility to pass on human knowledge to future generations, I could not but feel I must come and speak to you.

I speak on behalf of those who left their words as witnesses of history, such as the atomic bomb poems by Sadako Kuhihara who never gave up writing about human dignity in such a brave way to challenge against censorship; or by children who expressed their wish to live despite the harsh realities of the atomic bombings. To my great regret, many of those people are not here with us today. One more person of wisdom who has led me to come here today is Eva Hoffman, a writer of the second generation of the Holocaust, now living in England after many years of exile. So, I would like to begin with her words, handed to me as a translator of her essay on the Holocaust.

I would like to introduce you to the very impressive words of Eva Hoffman's After Such Knowledge, an essay titled with a quotation from T. S. Eliot’s poem, Gerontion. First, I intended to have put the words to my today’s key-note speech, but as they are completely untranslatable into Japanese, I gave up on the idea and called it “Memories for the Future” instead. Hoffman’s essay, subtitled A Meditation on the Aftermath of the Holocaust, was published in 2004 as a very contemplative criticism on the problems of the modern world from a broad historical point of view. The tragedies of 9/11 sharply reminded her of the Holocaust: an era from which, she claimed, we should have learned.

As many of you know, Hoffman was born in Poland in 1945, her Jewish parents having survived the Holocaust by hiding in a farmer’s barn in Ukraine where they were supported and helped by many kind strangers.

After the war, the family moved to Krakow but they decided to emigrate to Canada to escape from the threat of anti-Semitism at that time. Eva was 13 years old when she suddenly lost her homeland and mother-tongue, which traumatized her for a long time. It was only after becoming a writer in her second language that she could express these deep feelings from her childhood and finally liberate herself from the overwhelming sense of loss that had overshadowed her life.

Having taken her first step as a writer of the second generation of the Holocaust, Hoffman began her writing career. What is important to notice is that she had the strong sense of being an indirect victim of the Holocaust in a different way from the first generation.

As a child of the first-generation Holocaust sufferers, she had to witness the secret pain her parents experienced even after the war, yet she could never share the immediate pain with them. Overwhelmed by these phantoms of the past which she had never personally experienced, she felt strongly that the silent voices of her parents should be heard by the world.

She had to bear the burden of this trauma alone, and overcome it the same way.

I became aware of the second generation's traumas only by translating Hoffman’s heart-rending words. The unredeemable pain the 20th century had inflicted was suffered not only by the first generation: it was deeply imprinted in the second generation’s psyche.

What Eva Hoffman wanted to express with the title After Such Knowledge seems to me to be twofold. On the one hand the knowledge did not literally signify the facts of history; the implication of wisdom gathered through human will and consciousness. On the other, as the term “after” implies, the following generation should be responsible for turning the knowledge of the horrible past into something more constructive, incorporated with “wisdom” towards the future. In other words, we can say that the meanings of the disastrous past that cost so many people's lives could be found by those who come after. Those prisoners of the Auschwitz, for example, were not fully aware of the incomprehensible facts; they never knew at the time what was really happening, nor why.

It was only after the war that the cause of the unprecedented atrocities, the deaths of as many as six million people, was made clear and the historical background of the Holocaust was revealed to the world through numerous records and witnesses that had been discovered after deliberate research and examination.

As such, unfulfilled desires and desperate longings of the atomic-bombed victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki would be heard and recognized in the truest sense of the meaning by those who come after – in order to understand not only the memory of the past but also of the future. If the knowledge of the past could be turned into the legacy of wisdom, historical facts would be humanized by the legacy of those people’s determination, passed down through generations. Whether memories can live on or not depends on how the sense of relationship is consciously maintained through the generations.

Eva Hoffman showed us how to do it in her insightful book. Discussing it with her, I realized the ultimate goal of “knowledge” as she perceived it was “reconciliation.” That is why I translated the title into Japanese with sense of “memories for reconciliation”: not in the superficial sense of forgiveness, but in the deeper sense more akin to dialogical negotiation. “Reconciliation” in Eva Hoffman’s terms is a very difficult thing to achieve: indeed, all but impossible to reach. However, it is an idea that should always be explored as long as human beings necessarily live with others.

It is a very difficult – sometimes even painful – thing to do. Conflicts, a sense of absurdity, or recognition and acceptance of what seems to be completely ambivalent should be painfully experienced. However, such experiences surely change something inside ourselves; the most important change would be our consciousness of “others”, even if they are historical figures whom we have never met. We invite “others” into our own realm of life, into our story and into our sense of history. This how “memories” for the future are created inside us. In these memories, there is a certain reconciliation. It would be the reconciliation of the past with present, of the others with ourselves, and even of the present self in reality and the imagined one in our mind.

In different contexts, Hoffman points out in her book that the meetings of the Holocaust survivors with the persecutors, therapies, and the museums themselves in fact function as promoting “reconciliation”. To face reality above all is essential to accept what we tend to ignore, otherwise our will to understand the other would never be attained. It is absolutely a matter of ethics with which we can see through what is really necessary in order to understand the world as a whole. To accept the other, we need to change ourselves. In this sense, negotiation is not only enacted between the other and the self, but also between our own selves. In translating Hoffman’s harsh reality, I need to respond to her words in a different language. This is also a very challenging, yet meaningful, experience for me.

As time passes, there is a sense almost of urgency that the past should be kept; the voices of those who have direct experience should be recorded; and the history should not be forgotten. In Japan, obviously. However, do we have to be so pessimistic? How about thinking this way? Because of the passage of time, and with the benefit of distance, we can gradually create wisdom from knowledge, just as Eva Hoffman could meditate deeply on her memory of the past, from her perspective as the second generation.

In a different way from that in which the first generation looked at their direct experience, those who come after could search for reconciliation with the wisdom they have acquired. The will to lead from tragedy to reconciliation might open a new perspective to “memory” toward the future. It would be a new horizon explored through memory.

Time is not what erases the fact. Time is, rather, what saves memory from forgetfulness, and to create new arena of relationships instead. It is what we call reconciliation from which we can step forward toward the future. As an academic of Holocaust literature, I have true confidence in declaring it is not at all an empty idea but absolutely an insightful idea full of inspiration and wisdom, as literature itself has proved.

How is Victor Frankl perceived for example? As a psychiatrist he objectively witnessed human behaviors in the death camp, and recorded in his book there were many prisoners who could keep their dignity even when experiencing such inhumanity. There were some who gave their last piece of bread to the dying and others who gave kind words to others. It was an absolute truth of humanity. And their will to stay human outlived their existence, and told us the truth in the human history as a reality beyond time and space.

Three years have already passed since I returned to Oxford for my sabbatical year. That was when I invited Mrs Sayuri Yoshinaga, a famous actress who had dedicated herself to reciting poems written by atomic-bomb survivors for nearly a quarter of a century, to the University of Oxford to hold a poetry-reading event. For this special event, Mr Ryuichi Sakamoto, a famous pianist and composer living in N.Y., kindly came to collaborate with her. The chosen verses included not only the “atomic-bomb poems” such as Sankichi Toge’s famous Prologue and Sadako Kurihara’s I Will Deliver the Child, but also some pieces by Ryoichi Wago, published on Twitter soon after the devastation of Fukushima.

A very special and mysterious incident happened during the recital, but as the time is limited, I would ask you to read my book that includes the episode if you are interested. Anyway, it was a historic moment, because the historical memory of the Holocaust in the West resonated with the tragic legacy of the atomic bombings in the East. The human voices uttered from the realm of silence encountered in a small university chapel in Oxford in the 21st century.

Isn’t it amazing? Those two symbolic memories of human history became linked not because of the human pain, but because of the human will handed down beyond time and space.

A student in the audience commented: “I came to realize today that those who left their will in words responded in the most humane way to the most inhuman doings, the atomic bombings.” I was tremendously moved by his words. A young man who had no direct experience of war but had will to remember the indirect past-memory as a part of his own history, could understand expressions of the atomic bombings as “the most humane way of response”. I could not but feel deeply touched. He was impressed not by the pain described in the poems, but by the human dignity, humane emotions, and the human will strongly expressed in words. Atomic-bomb literature could be shared as human legacy with the people in different time and space.

“Power of expressions” is, for me, the innate power of all humans. Nobody can deprive us of it by force. Eva Hoffman herself could recover her own sense of self, overcoming the trauma of the loss of her homeland and mother tongue, because she fully activated her power of expression. She could also let us share her concept of “reconciliation” by her power of words, couldn’t she?

After a century of wars and atrocities, human beings have been suffering from a sense of loss and confidence in humanity. The past has not been erased, nor cut off. Aftermath and memories are still with us, kept and handed down by the human will at the same time. In this sense, past is still living with the present, against forgetfulness. Those who tried to express their experience in words and art are saving the past from oblivion, by their most humane way of responding to reality.

The names of many writers come to mind who so bravely show us the new horizons in which Hiroshima and Nagasaki are clearly viewed, even from the distance. Arundhati Roy in India, for example, whose Booker prize-winning The God of Small Things focused on the dark side of colonial history, put “Hiroshima” in her essay on the violence of modernity as an ultimate axis of human history. Her implication is that people’s perception of “Hiroshima” would be the way to liberate human beings from the shackles of violence. Mahmoud Darwish, a Palestinian poet and writer, wanted symbolically to write the letters HIROSHIMA, seeing an airplane in the grey sky after the Israeli attack against Beirut.

Here, I can see how the writers beyond the borders invite Hiroshima into their own realm of consciousness as a universal human legacy and wisdom that we should share with each other. This must be one channel to the world literature.

The critic Mark C. Taylor noted that Auschwitz and Hiroshima are what divided modernism and post-modernism, writing:

A century that began with utopian expectations every bit as grand as those of nineteenth-century romantics and idealists is eventually forced to confront the flames of Hiroshima and the ashes of Auschwitz. In the dark light of those flames and the arid dust of those ashes, modernism ends and something other begins. (Disfiguring: Art, Architecture, Religion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1922, 46-7)

After modernism, in the midst of skepticism and fragmentation, human beings had to recover. It must have been particularly difficult for those who had completely lost confidence in humanity after seeing Auschwitz and Hiroshima to recover the power to believe in humanity again. Economical and political recovery could not be achieved without the recovery of the human mind. The reconciliation with the past, with deeply imprinted traumas in the human psyche, culture, and history could not be avoided. In search of reconciliation, humans begin to find a little thread that could connect us with the past by which we come to understand how people lived through history and to know “human reality” as our living experience.

Human reality is, in other terms, the way we live as conscious self with dignity. This is why human will, kept even in the hell of the death camp ,could survive, illuminating human reality beyond history. This is why the words of the poet, “Give me back my people” after Hiroshima could tell us we need to be here. It is human dignity that is strongly illuminated in the works of literature.

In the title of my speech, “memories for the future”, I hope to express my wish and belief that the memories we are to create towards the future will be the signpost of human dignity.

Finally, I would like to introduce you to a little girl named Eluzunia. She is in Eva Hoffman’s After Such Knowledge in a small yet very impressive episode of her visit to Majdanek. I introduced the episode in my book, and so, let me quote some passages.

In translating Eva’s book, I encountered a very impressive episode of a nine-year-old girl who died in Majdanek. She left a piece of paper in her shoes on which she had written a little poem, set to the tune of a Polish lullaby she must have cherished in her heart with her childhood memory. It was only a four-line poem and she asked that if anybody were to find it, and sing it like a lullaby, she would really appreciate it.

The verse was sung at the Holocaust museum in Majdanek. Eva Hoffman was deeply moved by the sad yet beautiful tune when she visited the Museum. She wrote: “I believe this is the most piercing single verse I’ve ever heard and after all I have read, learned, and absorbed about the Shoah, the fragment strikes me with a wholly penetrating, unprepared sense of pity and sorrow. (After Such Knowledge)

I hoped that I could listen to the tune. In replying to my request, Eva finally found the music! And so, I wished it would some day be sung in Japan with my translation. The poem read as follows:

There was once little Eluzunia,

She’s dying all alone now.

For her daddy’s in Majdanek,

Her mummy in Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Acutely aware she would soon be killed, Eluzunia left a note in her shoes to ensure those who came after her know that she was here, lived, and died alone. Isn’t it a memory for the future? Never had she imagined that her wish would come true here in Japan. Her words and memory has been shared with you today, in Hiroshima, nearly 70 years after her death beyond borders.

In August 2012, Eluzunia's little poem was indeed recited with piano accompaniment – in front of the painting of Auschwitz in the Maruki Museum in Saitama. The melody played by the atomic-bombed piano was the very lullaby to which Eluzunia had set her poem. It was a moment when her memory for the future was definitely conveyed to Japan. Her will, and Hoffman’s words, made it possible. As a translator, I would be more than happy if my work had something to do with creating that moment.

Today, I would like you to listen to Eluzunia’s poem, set to the melody of the lullaby. It was sung by Erika Colon with the piano music by Michiru Ohshima in Tokyo in January 2013. So, it is a kind of epilogue to my speech today. Thank you very much.

Stress the power of the belongings of A-bombing victims

Kenji Shiga

Kenji Shiga, director of the Peace Memorial Museum, stressed the impact on young people of the personal belongings of victims of the A-bombing that have been donated to the museum.

He showed photographs of a stethoscope and scale used by a midwife who delivered a baby on August 6 and told a story of a college student who, after seeing those items, said, “I realized people just like me were living then. I was ashamed because I had thought of the A-bombing as just something in the past.”

Mr. Shiga also discussed other museum programs such as providing accounts of A-bomb survivors’ experiences to people overseas via a videoconference system and paintings done by high school students based on their interviews of survivors.

College students sent to NPT meeting

Nagasaki Youth Delegation

Keiko Nakamura, associate professor at the Nagasaki University Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition, talked about the Nagasaki Youth Delegation, which works with the city of Nagasaki and Nagasaki Prefecture to educate college students about the global situation regarding nuclear weapons. The group sent eight of its original members to Geneva for the second session of the Preparatory Committee for the Review Conference of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, which was held in April and May.

The students taught lessons on the A-bombing and peace to elementary and junior high school students in Geneva. They also held a debate on the abolition of nuclear weapons in August. “It’s important to pass down accounts of the A-bombing,” Ms. Nakamura said. “I’d like to set up a Hiroshima-Nagasaki Youth Delegation in 2015.”

Anna Shimoda, a senior at Nagasaki University and one of the original members of the delegation, said, “If students with knowledge in various fields put their heads together, there will be more opportunities to pass on the A-bombing experience.”

A need to share memories across borders

Kazumi Mizumoto

Kazumi Mizumoto, vice president of the Hiroshima Peace Institute of Hiroshima City University, proposed that in order to convey the story of the devastation of the atomic bombing to future generations it was necessary to take a look at the painful experiences of other countries as well. He stressed the need to share and pass on painful memories across borders.

He also described assistance in the form of teacher training and dental exams that Hiroshima has provided to Cambodia, which has experienced genocide and civil war. As a result, more local people took an interest in Hiroshima and the A-bombing, feeling that Hiroshima had had painful experiences similar to their own, he said.

He added that in order to ensure that the tragedies experienced by various nations are not repeated, people must have opportunities to develop an interest in other countries. “The sharing of tragic experiences is one challenge in the effort to pass experiences on to the next generation,” he said.

Problem of generating interest of indifferent young people

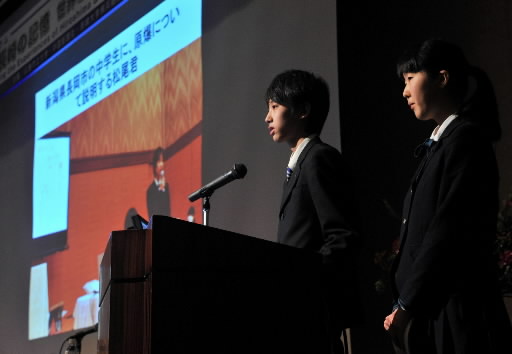

Junior Writers

Akira Tashiro, executive director of the Chugoku Shimbun Hiroshima Peace Media Center, gave an overview of the activities of the newspaper’s junior writers, who interview A-bomb survivors and conduct peace-related activities. Next, two of the junior writers gave a presentation on things they have learned and the issues they have faced in the course of their activities. Kantaro Matsuo, a third-year junior high school student (at left in the photo), said that when he heard atomic bomb survivors stress their opposition to nuclear weapons he began to think about peace and nuclear weapons. At the same time, he said finding ways to get indifferent young people interested in these issues was a challenge.

Yumi Kimura, a second-year high school student (at right in the photo), talked about her struggle to understand the depth of the suffering of the A-bomb survivors. “Through my junior writer activities, I came to feel that it’s important to take a good look at the reality of the A-bombing and to have a strong desire to convey that reality,” she said. “If there were junior writers around the world, there would be many more opportunities for people to think about peace from the perspective of children,” she added.

This special report was prepared by Rie Nii, Sakiko Masuda, Mayumi Nagasato and Shinichiro Origuchi. The photos were taken by Takahiro Inoue.

(Originally published on December 16, 2013)

◆Keynote speech (delivered by proxy)

Atsuko Hayakawa, 53, professor, Tsuda College

◆Panelists from overseas

Yves Kamuronsi, 32, deputy director, Kigali Genocide Memorial Center (Rwanda)

Takeshi Nakatani, 47, official guide, Auschwitz National Museum (Poland)

Sophearum Chey, 32, vice chief, Tuol Sleng Museum of Genocide (Cambodia)

◆Presenters of reports

Kenji Shiga, 61, director, Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

Keiko Nakamura, 41, associate professor, Nagasaki University Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition

Anna Shimoda, 21, member, Nagasaki Youth Delegation

Kazumi Mizumoto, 56, vice president, Hiroshima Peace Institute, Hiroshima City University

Akira Tashiro, 66, executive director, Chugoku Shimbun Hiroshima Peace Media Center

Kantaro Matsuo, 15, junior writer

Yumi Kimura, 17, junior writer

◆Moderators

Robert Jacobs, 53, associate professor, Hiroshima Peace Institute

Hitoshi Nagai, 48, associate professor, Hiroshima Peace Institute

Panel Discussion

Educational Programs

Understanding of background essential: Kamuronsi

Conducting tours using survivors’ words: Nakatani

Moderator: Many references have been made to the importance of education. What sorts of things are you doing, and what challenges do you face?

Kamuronsi: We have children of survivors and perpetrators of genocide studying in the same classrooms. It’s important for both groups to build a cooperative relationship. It’s not a matter of feeling responsible for what their parents’ generation did. It’s more important to understand the background behind what happened, including the propaganda – things like how their parents’ generation became involved and why the genocide occurred.

Chey: We conduct an educational program for students in which they interview their parents and grandparents about their experiences of the genocide. They have a dialogue among the family and record it.

The victims and perpetrators of the genocide will pass away eventually. Someday people will want to know the truth about what happened, so we want to preserve at our museum the accounts of their families’ experiences that the students gather.

Some people say that the younger generation doesn’t have a clear understanding of the genocide that took place in their country. We have to make sure that 50 or 100 years from now there won’t be people who want to return to the ideology of the Khmer Rouge, who carried out the genocide.

Mizumoto: I teach peace studies at Hiroshima City University. Even students who grew up in Hiroshima learning about the atomic bombing and peace aren’t aware of certain information, and we must provide it to them. I’m always trying to dig up stories that have been lost and get my students interested in them.

Nakatani: I’m not a Holocaust survivor, so when I give people tours I feel the stories of survivors are especially important. When I started giving tours 15 years ago, I sometimes gave tours to survivors, and I have modeled my gestures on theirs. I still can’t talk about the Holocaust in my own words. I mention certain survivors by name and recount what they said. I speak on their behalf.

Moderator: It can be traumatic to learn about distressing events at a young age. At what age do you start your educational programs and what sort of education is it?

Kamuronsi: You have to be careful when telling things to small children. When children ask what genocide is, how do you define it? Sometimes the bodies of relatives are found, and then there has to be some explanation what happened. I haven’t found the answer yet. I try to explain the background behind what happened through pictures and stories.

Nakatani: Our stance is that children should be at least 14 years old before they visit our museum because by that age they have developed a certain amount if cognitive ability. When I give tours to Japanese kids who are younger than that, I tell their parents about our policy. In many cases, children can properly understand the displays if they’ve prepared beforehand.

Learning from other countries

Gain a deeper understanding by analyzing causes: Mizumoto

Moderator: What do you feel about the significance and importance of teaching about genocide that has occurred in other countries?

Chey: It’s important to learn about the background behind the atomic bombings and genocide as well and to consider what happened. The backgrounds of each may differ, but the suffering is the same. We must cooperate, learn about these things together and then convey what we’ve learned to the next generation with a clear sense that the same thing must never happen again.

Kamuronsi: It’s important to learn from what has happened in other countries when considering how we can prevent genocide and war. The fact that there are still wars going on today shows that the lessons of the past haven’t been learned. That’s why it’s important to expand our knowledge.

Nakatani: We need to look at Auschwitz as something that could happen in any country in any age.

Mizumoto: It’s important to learn about the calamities have occurred in many areas and to analyze their causes. We have to learn what brought about the collapse of peace, leading to conflict, violence and killing among people who had lived together peacefully. If we do that, we can go beyond considering just the fact that a nuclear weapon, the ultimate form of violence, was used on Hiroshima.

Moderator: Do you teach about the prejudice and discrimination that lie behind genocide?

Mizumoto: Japan is an island nation, and compared to the continent it has had fewer opportunities for direct contact with other cultures. So I make a conscious effort to teach about Islam, Hinduism and the cultures of regions far removed from life in Japan. Japanese people tend to exclude people of other cultures when they don’t understand something. This can lead to violence. I try to get my students to understand that people may be different but we are all the same human beings.

Nakatani: There’s a big difference between Europeans and Japanese people in terms of the awareness of racial discrimination. In Europe people don’t say racist things in public, whereas in Japan there seems to be a sense that a certain amount of racism is no big deal. When the news media notice this sort of thing, they should speak out against it. Japan is too lenient when it comes to racism.

Message to young people

Calamities must not be forgotten: Chey

Moderator: We’d like to hear about the messages you are trying to convey to the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, particularly to young people.

Kamuronsi: I’d like to tell the young people of Rwanda, who are the future of the nation, about Hiroshima. I’d also like the young people of Hiroshima to tell their friends and families about the genocide in Rwanda and the efforts toward reconciliation. The young people of Rwanda and Hiroshima and the rest of Japan need to be able to relate to each other and get to know each other.

Nakatani: I’m glad to see quite a few young people here today. Young people are flexible and sensitive, and they have the courage to face whatever hardships they may encounter. Society needs young people like that, and I’d like them to work hard for the good of society.

Chey: On this visit to Hiroshima I’ve been able to learn a lot about the atomic bombing, and I’ve been able to talk with you at this symposium. I’ve been particularly impressed by the young people of Hiroshima. I want to convey Hiroshima’s message to the young people of Cambodia. I’d like to contribute to building peaceful relations among families, classmates and neighbors. We must not forget the catastrophes we have experienced.

Mizumoto: When passing on memories to the younger generation there’s a tendency to feel that everything must be handed down as knowledge. But that’s not the case. It’s important not only to pass on knowledge but also to give young people knowledge of how to avoid repeating these tragedies, after fully examining their inhumanity.

Memory Preservation and the Process of Recovery after Genocide in Rwanda

Yves Kamuronsi

My name is Yves Kamuronsi. I am the deputy director of the Kigali Genocide Memorial Centre, where I have been working since 2004.

I survived the genocide in Rwanda when I was 13 years old. I lost both my parents, my elder brother, my aunts, my cousins, my grandfather, and other members of my extended family.

I survived with my two sisters. At the time, one was 12 and the other was 9.

Today I am honored to be here at this conference, sharing with you the history of genocide in Rwanda and how Rwanda is preserving the memory of this tragedy for future generations and what is being done to rebuild the country.

My presentation is divided into three main parts.

Part 1

I will start my presentation by giving the historical background behind the genocide in Rwanda. I will then talk about what happened during this time, which I will call the 100 days of Genocide.

Part 2

In this part of my presentation, I will talk about the consequences of the genocide and how Rwanda has been able to cope.

Part 3

I will discuss the work of the Kigali Genocide Memorial Centre and briefly talk about various projects that are being developed at the Centre. This will include documenting and preserving the memory of the genocide and peace-building education, which is part of the recovery process.

"During my presentation I will use images to help illustrate the context."

Slide 1

Rwanda before genocide:

• 3 "ethnic" groups in Rwanda (Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa) living in harmony: categorised by social status.

• The polarisation between Hutu and Tutsi as a result of the change from social to ethnic categories began and progressively grew worse since the colonial era: Germany 1896-1916; Belgium 1916-1962.

• The policy of ‘divide and rule’ gradually built up resentment and a culture of hatred among the Hutu toward the Tutsi.

Slide 2

Genocide in Rwanda began in 1959:

• Dehumanization campaign: culminated in the first attempt of Tutsi ethnic cleansing with more than 20,000 Tutsi killed in 1959.

• Tutsi were forced to flee the country: important groups fled to Uganda, Burundi, Congo, and Tanzania.

• Development of exclusion policies and structures meant to nourish hate toward the Tutsi: education, employment, etc.

• Radio, the main media source in Rwanda, was also used to spread propaganda up until the execution of genocide in 1994.

Slide 3

100 Days of Genocide:

Genocide began on April 7, 1994.

More than 1,000,000 Tutsi were killed in the space of 100 days with the strategy of leaving none to tell the story (proven by Alison de Forges, U.S. human rights activist).

The killings occurred across the country.

Militias were trained to use all kinds of weapons and instruments to kill and inflict atrocities on Tutsis and their so-called Hutu allies: machetes, clubs, stoning, guns, rape, torture.

Slide 4

Consequences of genocide:

More than 120,000 children were orphaned.

100,000 widows and widowers. 75% of these survivors were infected by HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases.

Women developed cancer and other complications from their untreated wounds.

80% of survivors experience severe post-traumatic stress.

Slide 5

What marked the genocide in Rwanda:

• Speed of the violence: More than 1 million people killed within a period of less than 100 days.

• Efforts to totally annihilate the targeted people (Leave None to Tell the Story): criteria to select victims from perpetrators (9/10 Tutsi targeted killed, not one single targeted family which remained was unaffected by the genocide).

• Mass participation: Mass participation (1.05 million victims and more than 1.2 million perpetrators).

• Multiple and extreme forms of cruelty: systematic rape, hacking with machetes, burying victims alive, burning with fire, etc.).

• Victims overwhelmed by what was happening (normal life during genocide had stopped).

Slide 6

Challenges in Rwanda after 100 days of genocide:

Desolation of the population.

Compromised unity and social cohesion.

The image of Rwanda was tarnished abroad.

All the country’s key sectors were destroyed :

- Justice

- Economy

- Health

- Education

Question: How to preserve this memory while reconciling?

Slide 7

Justice:

More than 120,000 detainees accused of genocide crimes.

Gacaca court established, using a traditional form of justice. If the normal court system has been used, the process would have taken around 100 years.

Most people convicted in Category 3 and 2 have served their sentences and are now back in communities.

The Gacaca courts completed their work in 2012, after 10 years. They tried around 2 million cases.

Slide 7

Memory preservation:

• 8 genocide sites are being preserved at the national level as memorials.

• 30 sites are being preserved at the district level through Rwanda.

• 461 genocide sites are being preserved at the grassroots level.

Now I will discuss how “memory” is being used in Rwanda to teach the younger generation and aid peace-building.

In my presentation I will use the ‘’Kigali Genocide Memorial Centre’’ as a model.

Slide 8

Kigali Genocide Memorial:

• Located in Kigali, it is the nation’s most-visited memorial, inaugurated in 2004, on the 10th anniversary of the Tutsi genocide. It was created through a joint partnership of the Kigali City Council and the UK-based NGO, Aegis Trust.

• A place for survivors to bury their loved ones in dignity. Today more than 258,000 victims of genocide from Kigali are buried in 14 mass graves.

Slide 9

The Kigali Genocide Memorial Centre has 4 main parts:

• Graves and Memorial Gardens

• Exhibition

• Education Program

• Archive and Documentation

Slide 10

Exhibitions:

Three permanent exhibitions:

1. History about the genocide in Rwanda.

2. An exhibition about child victims of genocide.

3. History of other genocides around the world.

The main exhibition uses oral history testimonies, artifacts, human remains, and panels.

Slide 11

Education program:

Purpose of the education program:

• A response to genocide ideology in schools (anonymous letters to the surviving students, throwing their books, hatred messages in classrooms and bathrooms.)

• Building peace in the post-genocide society

• Positive understanding of identity and ethnicity

• Building trust and responsibility among young Rwandans

• Learning lessons from the past

Slides 12

Education program is attended by:

School students ranging in age from 12-20 years

Teachers in history and civic education

Community leaders

Slide 13

Main topics and content of the on-site education:

• Ideology of genocide

• Propaganda

• Difference between genocide and war

• The Holocaust and other cases of genocide

• Allaying the guilt of students who come from the families of survivors and perpetrators

• Critical thinking and problem solving

• Group discussions

Slide 14

Group discussion:

Discuss the following questions:

• What does “Never again” mean to you?

• Do my actions affect other people’s lives?

• As an individual, can I make a difference?

• What ways were used by the Nazis to discriminate against Jews?

• How much responsibility do you think the international community has for the genocide in Rwanda?

• What role do young people have in the process of peace building in Rwanda?

Slide 15

Peace building:

Mobile exhibition and educational workshops as a way forward:

• 2,500,000 Students in Rwanda

• Only 11,000 Students have attended our workshops at Kigali Genocide Memorial

• Transportation is a problem

• Targeting local community and teachers

• Using 3 testimonies and peace-building stories

Slide 16

Main objectives of peace building:

• Using a storytelling approach to educate as a form of best practice

• Sharing successful stories of peace initiatives around the country to stimulate discussions and debates about unity and reconciliation

• Developing critical thinking skills and promoting sustainable peace among youth and communities

• Presenting and discussing the role of youth in building a sustainable peace

Slide 17

Mobile exhibition content:

• Introduction to Rwandan history

• Selected peace-making stories from around the country

• Is the journey to peace possible?

• Children’s stories

Slide 18

Archive and documentation:

• 200 Survivors testimonies have been recorded

• 100 Remembrance and Exhumation ceremonies have been filmed

• 700 audiovisual tapes for Gacaca courts have been filmed, each 30 minutes

• 50 rescuers’ stories have been recorded: these are the stories of people who risked their lives to save others

Slide 19

Documentation of victims:

38,000 names of the victims collected

Around 5,000 pictures and other artifacts of the genocide victims are available in the archive

Slide 20

Genocide mapping:

A project of genocide mapping, using a GPS device, has been initiated to chart the detail of the genocide geographically. About 1000 roadblocks and 850 mass graves have been identified.

Slide 21

Purpose of Archive and Documentation Center:

• To create a permanent center for documentation to raise awareness of the atrocities that took place and to help those researching them.

• International genocide resource: Provide online access and work to help researchers and scholars worldwide.

• To produce both a physical and online documentation centre. Combined, these will provide a worldwide research tool on the genocide in Rwanda for academics, students, and independent researchers.

• A research centre and research library for students and academics in Rwanda, while also serving as a portal for Rwandan scholars to publicize their findings on the genocide to the rest of the world.

Slide 22

After almost 19 years, continuing the journey of recovery by:

• Achieving social cohesion through peace-building programs that reach out to Rwandan communities, the East African region, and beyond

• Focusing on healing the society from trauma

• Further development of educational programs, outreach programs, preserving memory through documentation, archiving, and exhibitions

• Making Rwanda a role model using lessons learned from the genocide

Conclusion

Next year Rwanda will commemorate 20 years since the genocide and the theme is Memory in Action.

In Rwanda today we are learning from the past to build a better future.