Teruko Yahata, 74, Fuchu town, Hiroshima

Aug. 9, 2012

Elementary school becomes crematorium

Mother’s haunting shout: “Let’s die together!”

Teruko Yahata (nee Kato), now 74, experienced the atomic bombing of Hiroshima at the age of eight. She is unable to forget the scene that took place right after the blast when her mother, Miyoko, grimly shouted “Let’s die together everyone!” and pulled a quilt from a closet and spread it over her four children and Ms. Yahata’s grandmother. They all snuggled tightly and gave warmth to one another. At that moment, her family became the most important thing in the world to her.

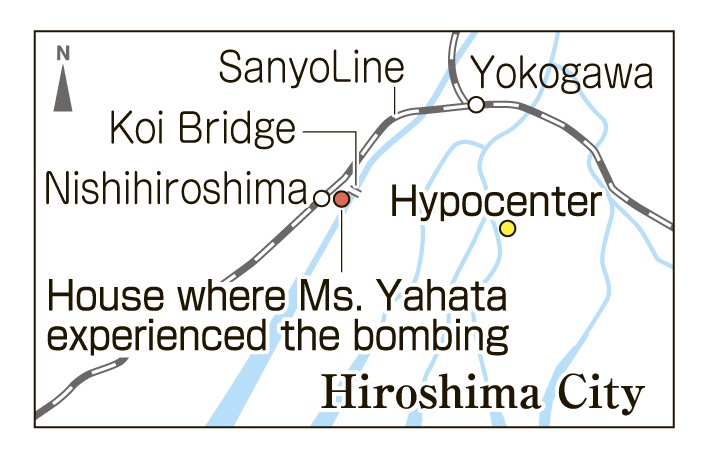

On August 6, she was with her family, including her father Takazo and her great-grandmother--eight people in all--at their home in Koihonmachi (in present-day Nishi Ward), about 2.5 kilometers from the hypocenter. The atomic bomb exploded at the moment she went into the backyard to ask a neighbor whether the “all-clear” had sounded. She recalls the sky lighting up in a white flash, and the next thing she knew, she had been blown back into the house toward the front door.

Her mother, thinking it was a big bomb and bleeding from glass fragments that had pierced her back, called Ms. Yahata and her siblings together and covered them with the quilt to prepare for more bombs. Ms. Yahata had a wound to her forehead, and her face was wet with blood, but her mother wiped it off.

Soon after they heard the shouting of someone from the volunteer fire corps--“Fire is breaking out!”--and all eight of them fled to a nearby air-raid shelter. For reasons that she doesn’t now recall, they weren’t able to rest there, though, and so they continued on to another shelter on the mountainside. But along the way, they were caught in a sudden shower of large raindrops--the radioactive “black rain” that fell in the aftermath of the blast. Finally, wet from the rain, they returned to the riverbank of the Yamate River, not far from their home. There Ms. Yahata saw large numbers of wounded staggering past, including people whose noses or whole faces had been crushed, or whose skin had peeled away and was gathering at their fingertips.

Afterwards, they went to her father’s aunt’s house in Momijidani, about 1.2 kilometers into the mountains, with her father’s cousin who had come in search of them. At Momijidani, the murmuring of the Yahata River and the sound of the cicadas welcomed them as if the horror of that day had never happened.

However, everything changed when Ms. Yahata went to Koi National School (now Koi Elementary School) with her father to receive treatment for the wound to her forehead. The school served as a relief station after the bombing. On the grounds of the school, where she had once attended an entrance ceremony amid falling cherry blossoms, she saw long ditches where bodies were dumped and burned. The number of bodies cremated at Koi National School is estimated at about 2,000. “The school I loved had become a crematorium,” Ms. Yahata said. Even now, when she recalls the scene, it makes her want to cry.

After the war, she endured a time of hunger yet lived life as fully as she could, experiencing marriage, children, and work. When she reached the age of 70, she thought she would begin relating her account of the atomic bombing, but then she suffered a heart attack. Although her health is still somewhat fragile, she started learning English in April. Sharing her dream, she said, “I want to talk about my A-bomb experience and the horror of nuclear weapons in English to people from other countries.” She appealed to young people to have appreciation for their parents and teachers and keep the importance of communication in mind. (Rie Nii, Staff Writer)

Hiroshima Insight: Air-raid shelters

Construction of air-raid shelters spread in 1944

During the war, people would temporarily evacuate to air-raid shelters in the event of an emergency.

In Japan, the construction of air-raid shelters began around 1941. A booklet published by the government in 1942 shows how to construct an “evacuation site” in homes and shops by, for example, digging a hole under the floor of a house or surrounding part of a room with store shelving.

The construction of air-raid shelters spread widely across Japan in 1944. It was proposed that such shelters should be made every five meters along busy streets where buses and trains run, and every ten meters along other bus routes. Several types of shelters were created. One was the “underground type” in which a hole was dug into the ground and the hole was then covered with boards and earth. Another was the “cave type” in which a cave was made in the side of a mountain. These shelters were constructed by families, neighborhoods, and communities.

In fact, many air-raid shelters from the war still exist today. According to a study conducted in 2009 by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, there are 9,850 dugouts, including air-raid shelters, under Japanese soil, with 891 of these in Hiroshima Prefecture.

Teenagers' Impressions

Family ties were destroyed in an instant

“Let’s die together!” Her mother’s words made Ms. Yahata aware of the importance of family ties. “Cherish your relationships with other people,” she told us. Her appeal sounds much like the sentiments of victims of last year’s big earthquake that hit eastern Japan. When we nearly lose a family member, we notice, for the first time, the importance of the family ties that we take for granted. Ms. Yahata’s story reminded me of how cruel the atomic bombing was, destroying these family ties in an instant. (Daichi Ishii, 15)

Create a society that supports orphans

Ms. Yahata said that when she noticed two butterflies flitting together, she recalled two children, apparently orphans, playing together for hours on the grounds of her elementary school, which had been transformed into a crematorium. The orphans of war and disaster, like earthquakes, must endure a lot of hardship to survive. To encourage them to have hope and go on, the community and the society have to provide them with support. (Masataka Tanaka, 17)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

At Koi Elementary School, a number of trees that survived the atomic bombing still stand. For example, behind the gym are cherry trees and gingko trees, and between the gym and the school building is a Himalayan cedar. The school is located more than 3 kilometers from the hypocenter, which means they can’t be designated official A-bombed trees, but in fact, they remain living witnesses to the day of the bombing.

After the blast, about 2,000 bodies were cremated on the grounds of the school. Because the school served as a relief station, scores of survivors from around the city thronged the site. The scenes of cremation are depicted in the book “Hiroshima: A Tragedy Never To Be Repeated,” written by Masamoto Nasu. Seven years ago, the level of the school grounds was built up, so the traces of that day can no longer be seen. However, a monument was raised by the local people, and on the evening of August 6 each year, a memorial ceremony to pray for the dead, and for peace, is held at the school. (Rie Nii)

(Originally published on May 14, 2012)