Yukio Fujimura, 84, Asaminami Ward, Hiroshima

Aug. 9, 2012

Unable to respond to cries for help

Conveying the horror of radiation for the earth’s future

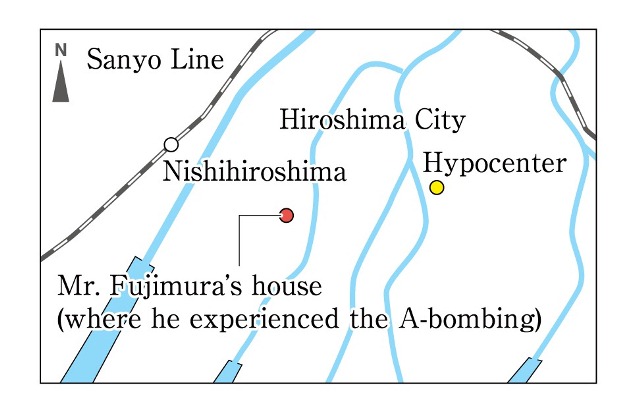

On August 6, 1945, the day the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Yukio Fujimura, now 84, was a boy of 17. He was at home in the Higashikannon district (part of present-day Nishi Ward), about 1.3 kilometers from the hypocenter, when the blast toppled the house on top of him. He lost consciousness, and when he came to, he felt a wave of heat and realized that the house was in flames. He struggled to free himself from the wreckage and finally noticed a small opening about 20 centimeters square. As a result of the hard labor and lack of food he had experienced during the war, he had become rail thin, his weight down to only about 40 kilograms, so he was able to squirm through that small opening and escape.

Mr. Fujimura was the first son of four brothers. Because his father, Yonekichi, had gotten injured at work, and his condition prevented him from holding down a job, Mr. Fujimura was forced to withdraw from Sanyo High School. He began working at a shipping company during the day and attending school at night.

In 1945, he was enlisted to help dig an air-raid shelter at the headquarters of the Second General Army, located in Futabanosato (part of present-day Higashi Ward). On August 6, however, he was feeling a bit ill and so he stayed home.

As he lay in bed, there was a sudden flash outside and a warm gust blew through the window. Moments later a huge boom shook the house. He was thrown into the air as beams and roof tiles fell, rendering him unconscious.

After fleeing from the house, he heard voices calling from all directions, crying out for help, but he didn’t see anyone. Mr. Fujimura was injured himself--his head bleeding, his body wounded--and he was in no condition to come to the aid of others.

He fled to a farm nearby and stayed there for three days. When he returned to where his house had stood, he encountered piles of bones in the area. Putting his hands together in prayer, he said, “I’m so sorry I couldn’t help you. Please forgive me.”

Four days later, at a relief station in Jigozen (now, Hatsukaichi), he was reunited with his family. His mother, Hide, was overjoyed to see him again. “You made it, Yukio! I’m so glad!” she said in tears.

On the morning of the bombing, Mr. Fujimura’s parents and two younger brothers were at home, too. After the blast, they called for him, but heard no reply. When the flames came, they were forced to flee. His other brother, Kanzo, a third-year student in national school (present-day elementary school) at the time, was wounded in the bombing, his body littered with shattered glass. He died on August 7.

Around 20 days later, Mr. Fujimura and his family returned to the site where their house had been and raised a shack on the same spot. They lived there for about a year, despite the cracks in the walls that forced them to snuggle together to endure the cold winter. His father’s injury, which he had suffered before the bombing, became infested with maggots and he passed away in April 1946.

Mr. Fujimura later landed a job at Dendenkosha, the forerunner of NTT (Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Corporation). At around the age of 60, after he had retired, he developed a condition that affected the bones in his neck. It isn’t clear what caused this condition, but Mr. Fujimura believes the atomic bombing is to blame. Today, he uses a wheelchair.

Following the accident at the nuclear power plant in Fukushima Prefecture, triggered by the earthquake and tsunami, Mr. Fujimura’s feelings about nuclear issues have grown even stronger. “I want children to know how powerful and frightening radiation is,” he stressed. “For the future of our earth, we need to eliminate nuclear weapons and nuclear energy both. I hope young people will join hands for this cause.” (Sakiko Masuda, Staff Writer)

Expanding the role of a military city

In April 1945, Japan faced a deteriorating war campaign as the United States intensified its air attacks and invaded Okinawa in preparation for an anticipated assault on the mainland. In response, the Japanese Imperial Army positioned the headquarters of the Second General Army, with authority over western Japan, in the city of Hiroshima.

The headquarters of the First General Army was located in Tokyo and commanded eastern Japan. According to the book, “The History of War Damage in Hiroshima Prefecture,” published in 1988, placing the headquarters of the Second General Army in Hiroshima was intended to maintain Japan’s capacity to fight even if the nation were to be divided in half by the U.S. invasion.

Hiroshima had a history of serving as a military city. During the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-95), the Imperial Headquarters was located in Hiroshima, on the grounds of Hiroshima Castle. Ujina Port, found in today’s Minami Ward, was the departure site for soldiers heading into battle by ship.

Hiroshima’s role as a military city grew when the Second General Army headquarters was established here.

But when the atomic bomb exploded above the city, the buildings housing the headquarters, located about 1.8 kilometers from the hypocenter, were consumed by fire and largely destroyed.

Teenagers' Impressions

Unite for the abolition of nuclear weapons

Mr. Fujimura emphasized the foolishness of the United States and Russia brandishing nuclear arms to show their might. I felt his strong determination when he told us he feels a duty to convey the folly of possessing nuclear weapons. I’d like to join hands with other teens to help protect the future of the earth. (Kantaro Matsuo, 13)

A persuasive appeal for no nuclear power plants

Again and again, Mr. Fujimura said that it’s vital to rid the world of nuclear power plants. Coming from his own painful experience of the atomic bombing, his point of view is very persuasive. He told us that he hopes the young people of the world will unite to help abolish nuclear weapons. I want to start by conveying the things I’ve learned about the horror of radiation to the people of the world. (Yuka Iguchi, 16)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

At the headquarters of the Second General Army, to which Mr. Fujimura had been assigned, the officer in charge of training was Prince Lee Woo of the imperial family of Korea. Serving the Japanese Imperial Army, he was killed in the atomic bombing.

Prince Lee Woo was born in 1912, two years after Japan annexed Korea. He came to Japan at the behest of the Japanese government. Apparently, he was transferred to Hiroshima after graduating from the military academy. After his death, his subordinate, lieutenant-colonel Hiromu Yoshinari, committed suicide because he felt responsible for the prince’s fate.

Prince Lee Woo’s name can be seen on the Monument in Memory of the Korean Victims of the A-bomb, which stands in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. During the time Korea was a Japanese colony, many people from the Korean Peninsula were brought to Japan and forced to work for the war effort or serve as soldiers--then perished in the atomic bombing. I hope this part of our history serves as an opportunity for us to contemplate peace in Asia. (Sakiko Masuda)

(Originally Published on May 28, 2012)

Conveying the horror of radiation for the earth’s future

On August 6, 1945, the day the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Yukio Fujimura, now 84, was a boy of 17. He was at home in the Higashikannon district (part of present-day Nishi Ward), about 1.3 kilometers from the hypocenter, when the blast toppled the house on top of him. He lost consciousness, and when he came to, he felt a wave of heat and realized that the house was in flames. He struggled to free himself from the wreckage and finally noticed a small opening about 20 centimeters square. As a result of the hard labor and lack of food he had experienced during the war, he had become rail thin, his weight down to only about 40 kilograms, so he was able to squirm through that small opening and escape.

Mr. Fujimura was the first son of four brothers. Because his father, Yonekichi, had gotten injured at work, and his condition prevented him from holding down a job, Mr. Fujimura was forced to withdraw from Sanyo High School. He began working at a shipping company during the day and attending school at night.

In 1945, he was enlisted to help dig an air-raid shelter at the headquarters of the Second General Army, located in Futabanosato (part of present-day Higashi Ward). On August 6, however, he was feeling a bit ill and so he stayed home.

As he lay in bed, there was a sudden flash outside and a warm gust blew through the window. Moments later a huge boom shook the house. He was thrown into the air as beams and roof tiles fell, rendering him unconscious.

After fleeing from the house, he heard voices calling from all directions, crying out for help, but he didn’t see anyone. Mr. Fujimura was injured himself--his head bleeding, his body wounded--and he was in no condition to come to the aid of others.

He fled to a farm nearby and stayed there for three days. When he returned to where his house had stood, he encountered piles of bones in the area. Putting his hands together in prayer, he said, “I’m so sorry I couldn’t help you. Please forgive me.”

Four days later, at a relief station in Jigozen (now, Hatsukaichi), he was reunited with his family. His mother, Hide, was overjoyed to see him again. “You made it, Yukio! I’m so glad!” she said in tears.

On the morning of the bombing, Mr. Fujimura’s parents and two younger brothers were at home, too. After the blast, they called for him, but heard no reply. When the flames came, they were forced to flee. His other brother, Kanzo, a third-year student in national school (present-day elementary school) at the time, was wounded in the bombing, his body littered with shattered glass. He died on August 7.

Around 20 days later, Mr. Fujimura and his family returned to the site where their house had been and raised a shack on the same spot. They lived there for about a year, despite the cracks in the walls that forced them to snuggle together to endure the cold winter. His father’s injury, which he had suffered before the bombing, became infested with maggots and he passed away in April 1946.

Mr. Fujimura later landed a job at Dendenkosha, the forerunner of NTT (Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Corporation). At around the age of 60, after he had retired, he developed a condition that affected the bones in his neck. It isn’t clear what caused this condition, but Mr. Fujimura believes the atomic bombing is to blame. Today, he uses a wheelchair.

Following the accident at the nuclear power plant in Fukushima Prefecture, triggered by the earthquake and tsunami, Mr. Fujimura’s feelings about nuclear issues have grown even stronger. “I want children to know how powerful and frightening radiation is,” he stressed. “For the future of our earth, we need to eliminate nuclear weapons and nuclear energy both. I hope young people will join hands for this cause.” (Sakiko Masuda, Staff Writer)

Hiroshima Insight: Second General Army headquarters

Expanding the role of a military city

In April 1945, Japan faced a deteriorating war campaign as the United States intensified its air attacks and invaded Okinawa in preparation for an anticipated assault on the mainland. In response, the Japanese Imperial Army positioned the headquarters of the Second General Army, with authority over western Japan, in the city of Hiroshima.

The headquarters of the First General Army was located in Tokyo and commanded eastern Japan. According to the book, “The History of War Damage in Hiroshima Prefecture,” published in 1988, placing the headquarters of the Second General Army in Hiroshima was intended to maintain Japan’s capacity to fight even if the nation were to be divided in half by the U.S. invasion.

Hiroshima had a history of serving as a military city. During the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-95), the Imperial Headquarters was located in Hiroshima, on the grounds of Hiroshima Castle. Ujina Port, found in today’s Minami Ward, was the departure site for soldiers heading into battle by ship.

Hiroshima’s role as a military city grew when the Second General Army headquarters was established here.

But when the atomic bomb exploded above the city, the buildings housing the headquarters, located about 1.8 kilometers from the hypocenter, were consumed by fire and largely destroyed.

Teenagers' Impressions

Unite for the abolition of nuclear weapons

Mr. Fujimura emphasized the foolishness of the United States and Russia brandishing nuclear arms to show their might. I felt his strong determination when he told us he feels a duty to convey the folly of possessing nuclear weapons. I’d like to join hands with other teens to help protect the future of the earth. (Kantaro Matsuo, 13)

A persuasive appeal for no nuclear power plants

Again and again, Mr. Fujimura said that it’s vital to rid the world of nuclear power plants. Coming from his own painful experience of the atomic bombing, his point of view is very persuasive. He told us that he hopes the young people of the world will unite to help abolish nuclear weapons. I want to start by conveying the things I’ve learned about the horror of radiation to the people of the world. (Yuka Iguchi, 16)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

At the headquarters of the Second General Army, to which Mr. Fujimura had been assigned, the officer in charge of training was Prince Lee Woo of the imperial family of Korea. Serving the Japanese Imperial Army, he was killed in the atomic bombing.

Prince Lee Woo was born in 1912, two years after Japan annexed Korea. He came to Japan at the behest of the Japanese government. Apparently, he was transferred to Hiroshima after graduating from the military academy. After his death, his subordinate, lieutenant-colonel Hiromu Yoshinari, committed suicide because he felt responsible for the prince’s fate.

Prince Lee Woo’s name can be seen on the Monument in Memory of the Korean Victims of the A-bomb, which stands in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. During the time Korea was a Japanese colony, many people from the Korean Peninsula were brought to Japan and forced to work for the war effort or serve as soldiers--then perished in the atomic bombing. I hope this part of our history serves as an opportunity for us to contemplate peace in Asia. (Sakiko Masuda)

(Originally Published on May 28, 2012)