Hideo Ishida, 81, Naka Ward, Hiroshima

Aug. 9, 2012

Fear of discrimination kept his A-bomb experience a secret

Obtained the survivor’s certificate 51 years after the bombing

Hideo Ishida, 81, long held the fear that his exposure to the atomic bombing would lead to discrimination and other difficulties. Even when he got married, he was reluctant to reveal his A-bomb experience to his wife. However, in 1996, 51 years after the atomic bomb was dropped, he finally obtained the A-bomb Survivors Certificate. Now he makes the appeal: “Please convey the fact that many young people died that day and the survivors have suffered for many years.”

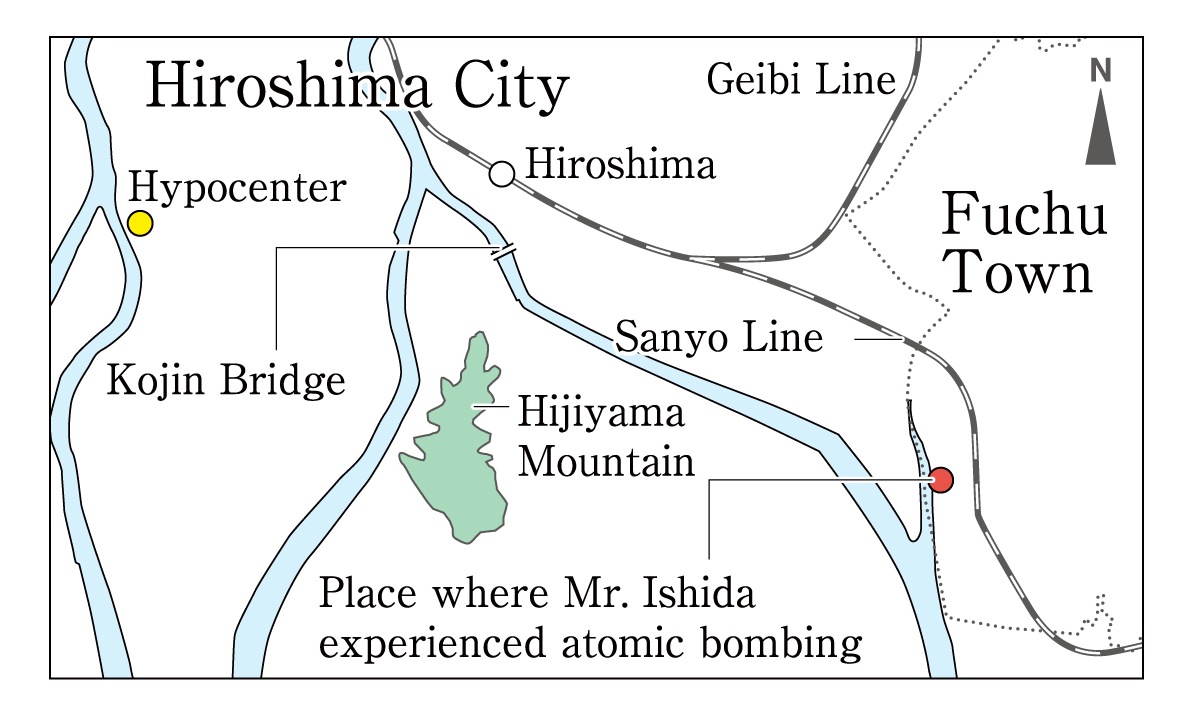

On August 6, the day of the bombing, Mr. Ishida was a second-year student at Sanyo Junior High School. He had been mobilized to work at a factory located near today’s Mazda automobile plant in the Fuchu district, roughly 4.3 kilometers from the hypocenter. The factory had ties to the Kure Naval Arsenal.

At that moment, though, he had no work to do so he was outside, on the bank of the Fuchu River. He then heard the buzz of an American plane, a B-29 bomber. Right afterward, there was a flash of white light above the city center, over Mt. Hijiyama. The mountain looked as if it was floating in the sky, like an aircraft carrier on the water.

The ball of light spread out toward Mr. Ishida, like rippling water, and when it arrived above him, he was blown into the air. Unharmed, he headed in the direction of downtown Hiroshima, with four classmates, in search of his father, who was working at a factory in the Ozu area, now part of Minami Ward.

When he reached the factory, however, he was unable to locate his father. Venturing on to the city center, he passed people with faces that had been severely burned and arms peeled clean of their skin. As he stood on Kojin Bridge, he saw that the city had become a sea of fire. He went across the bridge and moved along the Enko River for a while, arriving at Mukainada Station. From there he followed the railroad tracks back to his maternal grandparents’ house in the Nakano area, part of present-day Aki Ward, where he had been staying as a result of an earlier evacuation.

His father was wounded in the factory, his back pierced by flying fragments of glass, and sought treatment at a hospital before returning home that night.

After the war, when Mr. Ishida was in his late 20s, each time a prospective marriage partner appeared, his mother would confirm whether or not the woman was an A-bomb survivor. At the same time, he withheld the truth that he himself had experienced the atomic bomb. Smiling grimly, he recalled: “I talked with my friends about it and we came to the conclusion that holding the A-bomb Survivor’s Certificate would make it hard for us to find someone to marry.”

His wedding day came in 1960, and when his wife became pregnant, he shared his A-bomb experience with her for the first time. His wife simply listened. His two children and two grandchildren have so far suffered no serious health concerns.

He first sought to obtain the A-bomb Survivor’s Certificate around 1975. This was prompted by a conversation with his first son, who was in junior high school at the time. When Mr. Ishida tried to speak about the atomic bombing with his son, the boy criticized him, saying, “Why are you talking about the atomic bombing when you didn’t even get the A-bomb Survivor’s Certificate?”

He applied for the certificate at city hall, but his application was rejected because he was unable to find two witnesses who were older than 14 at the time of the A-bomb blast. When his grandchild entered junior high, he tried again, and this time was issued the certificate as someone who had “entered the designated area of the city within two weeks of the atomic bombing.”

Mr. Ishida retired two and a half years ago and now actively shares his A-bomb account with others. “If nuclear weapons are used, they will destroy the earth,” he said. “I’d like young people to take over our anti-nuclear views.” (Rie Nii, Staff Writer)

Hiroshima Insight: Those who entered the hypocenter area after the bombing

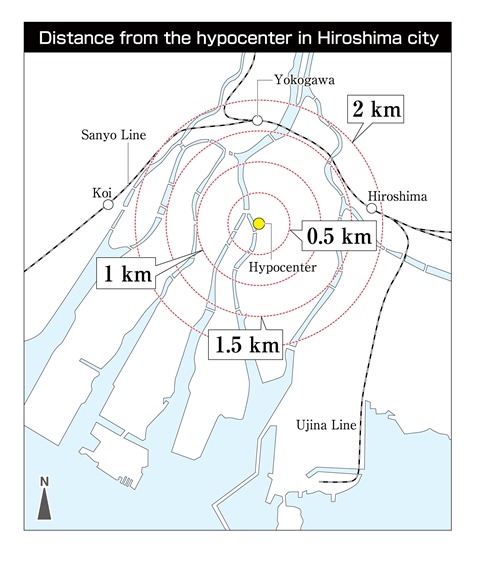

The Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law stipulates that, following the atomic bombings, those who entered an area within roughly 2 kilometers of the hypocenter by August 15 (in the case of Hiroshima, by August 20) can also be certified as atomic bomb survivors.

In Hiroshima, the 2-kilometer boundaries are located in Misasahonmachi 2 (in present-day Nishi Ward) to the north, Sendamachi 3 (in present-day Naka Ward) to the south, Enkobashicho (in present-day Minami Ward) to the east, and Fukushimacho (in present-day Nishi Ward) to the west.

Other categories of certified A-bomb survivors are those who were in the city when the bomb was dropped and suffered a direct exposure, those who were engaged in providing medical aid and care to the victims, and the fetuses of such women.

People in these categories can be certified as atomic bomb survivors and obtain the A-bomb Survivor’s Certificate by submitting the necessary paperwork.

As of the end of March 2011, the Hiroshima city government has issued the A-bomb Survivor’s Certificate to 68,886 people. Among them, the number of people who experienced the atomic bombing directly stands at 41,990 people (61%) while 16,753 people (24.3%) entered the 2-kilometer area around the hypocenter in the aftermath of the blast. In Japan, the total number of A-bomb survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki is estimated at 219,410 people.

Teenagers' Impressions

Sad photos of lost students

Mr. Ishida showed us eight photos. The first seven photos were taken at the time of the entrance ceremony at Sanyo Junior High School. To include all of the new students, seven photos were needed. The eighth photo, though, was taken at the graduation ceremony, and because so many students were killed in the bombing, only one photo was needed for the remaining students. It was really sad seeing these photos side by side.

Mr. Ishida told us, “The victims of war and the atomic bombing suffered, but their families have suffered, too. We can’t continue to make people suffer like that.” I want to tell others about Mr. Ishida’s account, as well as the experiences of my late grandparents, who were also A-bomb survivors. (Masataka Tanaka, 17)

Depriving people of their humanity

When he said that he became numb to the sight of the dead bodies around him, that scared me. War and the atomic bombing deprived people of their humanity, I thought. It must leave a deep scar in their hearts.

Mr. Ishida hopes that people will “continue listening to the survivors’ experiences of the bombing and never wage war again.” I want to convey his wishes to my friends and to others around me. (Mako Sakamoto, 15)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

Since his retirement two and a half years ago, Mr. Ishida has been involved in researching the atomic bombing as well as sharing his A-bomb experience. One subject of his research is the fate of the first-year students of Sanyo Junior High School. On the day of the bombing, August 6, the first-year students, who were one year younger than Mr. Ishida, were mobilized to work outdoors, helping to tear down buildings to create fire lanes in the event of air raids. Most of them perished in the blast. As a result, just one photo could contain the entire class after the war, compared to the seven photos needed to include all the students at the school’s entrance ceremony.

Mr. Ishida told us: “If you visit a cemetery in the city this summer, please look at the headstones.” You’ll find many people who died on August 6, 1945, he said. And you’ll feel how each one of them had a life and a family. (Rie Nii)

(Originally published on June 12, 2012)