Taeko Miyoshi, 76, Fuchu, Hiroshima Prefecture

Oct. 5, 2012

Suffered a final parting from her mother, who couldn’t escape

Accepted an arranged marriage with an A-bomb survivor

“Mom!” Taeko Miyoshi cried, as a stranger carried her away from the scene. Her mother Hisano could only wave with a bloody hand. It was the final parting of mother and daughter.

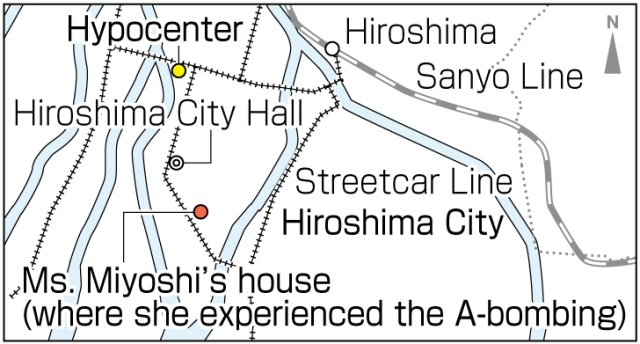

Ms. Miyoshi was 8 years old on August 6, 1945, the day the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. She was at home in the Higashisenda district (part of present-day Naka Ward) and seated on the floor with her mother and grandmother, Tsune. Their house was located about 1.2 kilometers from the hypocenter.

At the instant “a big fireball came toward us,” she was blown into the air. When she came to, she discovered that she was outside, on the ground. Ms. Miyoshi, her mother, and her grandmother had all been hit by flying fragments of glass and were covered in blood. There was a gaping hole in her mother’s throat.

Her mother tried to speak, but the breath was escaping through the hole in her throat and she was unable to sound out words. Ms. Miyoshi recalled, “It may be that some internal organ was protruding through the hole as the wound bled. It was a hopeless situation.”

Fire then began to stalk the house. A man passing by said to Ms. Miyoshi, “You’ll die if you stay here,” and he picked her up and carried her to some streetcar tracks, about 200 meters away. “I didn’t want to be separated from my mother,” she said. “That was the last time I saw her.” Her mother’s remains were never found. Her grandmother was brought to a temple in the Kaita district and cared for there, but a year later she died of a high fever of unknown cause.

Ms. Miyoshi was then carried by truck to the bank of a river, probably the Ota River. She spent the night there in the open air. The next day, she was reunited with a girl from her neighborhood, then made the trek to an area known as Hataka Village (part of today’s Aki Ward), where her grandparents’ house was located. “I think I was given a ride in a truck,” she said. “But I don’t remember clearly.”

After that, she was brought to Hataka National School (now, Hataka Elementary School), which was serving as a relief station in the aftermath of the bombing. Laid on a classroom floor, she soon fell unconscious. When she came to, she learned that the war was over.

At night in the classroom, she heard voices crying out in pain, even calling for death. “In the moonlight, they looked like ghosts,” she recalled. “It made me lonely and scared.” When morning came, about half of them were dead.

Ms. Miyoshi’s aunt took her from the school to her house in Etajima (now, Etajima City), where she began her recovery that September. The following summer, her father, Kuwaichi, ended his military service and, together, father and daughter moved into a cottage owned by relatives in Hataka Village.

Because there were rumors that “A-bombed mothers would bear abnormal children,” Ms. Miyoshi decided that she would never marry. However, she later received a proposal in an arranged marriage. When she found out that the man was an A-bomb survivor, too, she agreed to marry him, hoping that they would understand one another since they were both survivors.

Her husband Chuzo, 81, experienced the bombing while working as a “mobilized student” for the war effort in the Kasumicho district (part of present-day Minami Ward). He became an orphan after his parents and older brother were killed, and was cared for by his uncle, who lived in the countryside of Hiroshima Prefecture, in a place called Daiwa (now part of Mihara City).

“If the atomic bombing hadn’t happened, I could have lived a normal life,” she said. This is why she hopes “young people will do their best so they can live in peace.” (Rie Nii, Staff Writer)

A-bomb orphans: Hunger and crime resulted from the A-bomb tragedy

Children whose parents died in the atomic bombing are known as “A-bomb orphans.” The number of A-bomb orphans from the Hiroshima bombing has been estimated at between 4,000 to 5,000, but the total isn’t clear since it seems this figure includes some children whose mother or father was still alive, but were living on the streets because of poverty.

Two days after the bombing, Hijiyama National School (now, Hijiyama Elementary School in Minami Ward) became a shelter for orphans (called “lost children” at the time). At one time the shelter housed about 200 children, but many children died there.

In December 1945, the Hiroshima War Orphans Foster Home was established in the Itsukaichi district (part of present-day Saeki Ward). Then, in September 1946, the Hiroshima Prefectural War Orphans Foster Home Ninoshima Gakuen was established on Ninoshima Island, just south of the city, and this shelter, among others, gave the city more facilities to take in the orphaned children. A campaign for the “moral adoption” of the city’s orphans was also initiated by people of the United States and Japan, who would exchange letters with the children and send them money and gifts.

Still, there were some children who did not find a place to live, and died as a result of hunger and the cold of winter, or became involved in crime and lost their lives. The atomic bombing had a huge impact on the lives of innocent children.

[Facilities for A-bomb orphans and children]

1. Name of facility

2. When it opened

3. Number of children

1. Hiroshima Shinsei Gakuen

2. October 1945

3. 75

1. Hiroshima War Orphans Foster Home

2. December 1945

3. 77

1. Hiroshima Prefectural War Orphans Foster Home Ninoshima Gakuen

2. September 1946

3. 185

1. Hikari no sono setsuri no ie

2. August 1947

3. 83

1. Hiroshima Shudoin

2. April 1948

3. 98

1. Roppo Gakuen

2. January 1949

3. 96

Source: “Shinshu Hiroshima City History”

(Note: The number of children at the facilities varied, depending on the time.)

Teenagers’ Impressions

Stronger appeals to those from overseas

Ms. Miyoshi lost her loved ones in the atomic bombing. Even now, there are fragments of glass stuck in her body and she suffers from the aftereffects of that time.

A lot of nuclear weapons still exist in the world today. When representatives of other nations attend the Peace Memorial Ceremony held each year on August 6, we should encourage them to visit various monuments dedicated to the A-bomb victims and listen to the accounts of A-bomb survivors in order to understand the cruelty of the atomic bombing more deeply. (Takeshi Iwata, 13)

Avoiding conflict

I was impressed by her words when she said she hopes that people today and in the future will do their best to avoid conflict. I hope that the current territorial disputes between Japan and China, and Japan and Korea, will be settled soon. Also, I realized that we can be happy due to the fact that we don’t have to fear for our lives, as people did during the war. If a lot of people would listen to the stories of A-bomb survivors, they would realize that, too. (Reiko Takaya, 15)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

When the atomic bomb was dropped, Taeko Miyoshi was in the third grade of elementary school. Until August 2, she had evacuated from Hiroshima and was living in her aunt’s house in Etajima with her mother and grandmother. However, at the end of July, a military fleet at anchor near Noumi Island (part of present-day Etajima City) was attacked and she saw the bodies of soldiers who tried to swim away from the ships but were killed, their remains floating on the sea. She also witnessed people on the island cremating the bodies on the shore. Frightened by these events, Ms. Miyoshi pleaded with her mother and grandmother for the three of them to return to Hiroshima. On August 3 they headed back to the house in the Higashisenda district.

The upper left side of her body, nearest a window when the atomic bomb exploded, was pierced by numerous fragments of shattered glass. As a result, she has scars by her left eye, on her left wrist, on her neck, and on her chest. Even today, a fragment still lodged in her neck sometimes causes her pain. “This fragment,” she explained, “is the only thing left that belongs to our house in Higahisenda, so I thought I should keep this ‘treasure’ and never have it removed.” Her mother’s remains were never found and she has no mementos of her mother, so the glass fragment in her neck is the only thing still linking parent and child.

Even today, her husband, an A-bomb orphan, never speaks about the atomic bombing. Ms. Miyoshi has been reluctant to describe her experience of the bombing to their two daughters in any detail because she worries about their feelings. “I wouldn’t want them to feel anxious over the fact that they’re children of A-bomb survivors,” she said. She recalls that when her younger daughter was a child, the girl was physically weak, and Ms. Miyoshi sometimes thought, “I shouldn’t have had her.”

Now, thinking about how she survived for so long, she believes that her mother, who didn’t want to die, has helped keep her alive. I sensed the deep affection and concern she feels for her mother and her daughters. (Rie Nii)

(Originally published on September 11, 2012)

Accepted an arranged marriage with an A-bomb survivor

“Mom!” Taeko Miyoshi cried, as a stranger carried her away from the scene. Her mother Hisano could only wave with a bloody hand. It was the final parting of mother and daughter.

Ms. Miyoshi was 8 years old on August 6, 1945, the day the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. She was at home in the Higashisenda district (part of present-day Naka Ward) and seated on the floor with her mother and grandmother, Tsune. Their house was located about 1.2 kilometers from the hypocenter.

At the instant “a big fireball came toward us,” she was blown into the air. When she came to, she discovered that she was outside, on the ground. Ms. Miyoshi, her mother, and her grandmother had all been hit by flying fragments of glass and were covered in blood. There was a gaping hole in her mother’s throat.

Her mother tried to speak, but the breath was escaping through the hole in her throat and she was unable to sound out words. Ms. Miyoshi recalled, “It may be that some internal organ was protruding through the hole as the wound bled. It was a hopeless situation.”

Fire then began to stalk the house. A man passing by said to Ms. Miyoshi, “You’ll die if you stay here,” and he picked her up and carried her to some streetcar tracks, about 200 meters away. “I didn’t want to be separated from my mother,” she said. “That was the last time I saw her.” Her mother’s remains were never found. Her grandmother was brought to a temple in the Kaita district and cared for there, but a year later she died of a high fever of unknown cause.

Ms. Miyoshi was then carried by truck to the bank of a river, probably the Ota River. She spent the night there in the open air. The next day, she was reunited with a girl from her neighborhood, then made the trek to an area known as Hataka Village (part of today’s Aki Ward), where her grandparents’ house was located. “I think I was given a ride in a truck,” she said. “But I don’t remember clearly.”

After that, she was brought to Hataka National School (now, Hataka Elementary School), which was serving as a relief station in the aftermath of the bombing. Laid on a classroom floor, she soon fell unconscious. When she came to, she learned that the war was over.

At night in the classroom, she heard voices crying out in pain, even calling for death. “In the moonlight, they looked like ghosts,” she recalled. “It made me lonely and scared.” When morning came, about half of them were dead.

Ms. Miyoshi’s aunt took her from the school to her house in Etajima (now, Etajima City), where she began her recovery that September. The following summer, her father, Kuwaichi, ended his military service and, together, father and daughter moved into a cottage owned by relatives in Hataka Village.

Because there were rumors that “A-bombed mothers would bear abnormal children,” Ms. Miyoshi decided that she would never marry. However, she later received a proposal in an arranged marriage. When she found out that the man was an A-bomb survivor, too, she agreed to marry him, hoping that they would understand one another since they were both survivors.

Her husband Chuzo, 81, experienced the bombing while working as a “mobilized student” for the war effort in the Kasumicho district (part of present-day Minami Ward). He became an orphan after his parents and older brother were killed, and was cared for by his uncle, who lived in the countryside of Hiroshima Prefecture, in a place called Daiwa (now part of Mihara City).

“If the atomic bombing hadn’t happened, I could have lived a normal life,” she said. This is why she hopes “young people will do their best so they can live in peace.” (Rie Nii, Staff Writer)

Hiroshima Insight

A-bomb orphans: Hunger and crime resulted from the A-bomb tragedy

Children whose parents died in the atomic bombing are known as “A-bomb orphans.” The number of A-bomb orphans from the Hiroshima bombing has been estimated at between 4,000 to 5,000, but the total isn’t clear since it seems this figure includes some children whose mother or father was still alive, but were living on the streets because of poverty.

Two days after the bombing, Hijiyama National School (now, Hijiyama Elementary School in Minami Ward) became a shelter for orphans (called “lost children” at the time). At one time the shelter housed about 200 children, but many children died there.

In December 1945, the Hiroshima War Orphans Foster Home was established in the Itsukaichi district (part of present-day Saeki Ward). Then, in September 1946, the Hiroshima Prefectural War Orphans Foster Home Ninoshima Gakuen was established on Ninoshima Island, just south of the city, and this shelter, among others, gave the city more facilities to take in the orphaned children. A campaign for the “moral adoption” of the city’s orphans was also initiated by people of the United States and Japan, who would exchange letters with the children and send them money and gifts.

Still, there were some children who did not find a place to live, and died as a result of hunger and the cold of winter, or became involved in crime and lost their lives. The atomic bombing had a huge impact on the lives of innocent children.

[Facilities for A-bomb orphans and children]

1. Name of facility

2. When it opened

3. Number of children

1. Hiroshima Shinsei Gakuen

2. October 1945

3. 75

1. Hiroshima War Orphans Foster Home

2. December 1945

3. 77

1. Hiroshima Prefectural War Orphans Foster Home Ninoshima Gakuen

2. September 1946

3. 185

1. Hikari no sono setsuri no ie

2. August 1947

3. 83

1. Hiroshima Shudoin

2. April 1948

3. 98

1. Roppo Gakuen

2. January 1949

3. 96

Source: “Shinshu Hiroshima City History”

(Note: The number of children at the facilities varied, depending on the time.)

Teenagers’ Impressions

Stronger appeals to those from overseas

Ms. Miyoshi lost her loved ones in the atomic bombing. Even now, there are fragments of glass stuck in her body and she suffers from the aftereffects of that time.

A lot of nuclear weapons still exist in the world today. When representatives of other nations attend the Peace Memorial Ceremony held each year on August 6, we should encourage them to visit various monuments dedicated to the A-bomb victims and listen to the accounts of A-bomb survivors in order to understand the cruelty of the atomic bombing more deeply. (Takeshi Iwata, 13)

Avoiding conflict

I was impressed by her words when she said she hopes that people today and in the future will do their best to avoid conflict. I hope that the current territorial disputes between Japan and China, and Japan and Korea, will be settled soon. Also, I realized that we can be happy due to the fact that we don’t have to fear for our lives, as people did during the war. If a lot of people would listen to the stories of A-bomb survivors, they would realize that, too. (Reiko Takaya, 15)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

When the atomic bomb was dropped, Taeko Miyoshi was in the third grade of elementary school. Until August 2, she had evacuated from Hiroshima and was living in her aunt’s house in Etajima with her mother and grandmother. However, at the end of July, a military fleet at anchor near Noumi Island (part of present-day Etajima City) was attacked and she saw the bodies of soldiers who tried to swim away from the ships but were killed, their remains floating on the sea. She also witnessed people on the island cremating the bodies on the shore. Frightened by these events, Ms. Miyoshi pleaded with her mother and grandmother for the three of them to return to Hiroshima. On August 3 they headed back to the house in the Higashisenda district.

The upper left side of her body, nearest a window when the atomic bomb exploded, was pierced by numerous fragments of shattered glass. As a result, she has scars by her left eye, on her left wrist, on her neck, and on her chest. Even today, a fragment still lodged in her neck sometimes causes her pain. “This fragment,” she explained, “is the only thing left that belongs to our house in Higahisenda, so I thought I should keep this ‘treasure’ and never have it removed.” Her mother’s remains were never found and she has no mementos of her mother, so the glass fragment in her neck is the only thing still linking parent and child.

Even today, her husband, an A-bomb orphan, never speaks about the atomic bombing. Ms. Miyoshi has been reluctant to describe her experience of the bombing to their two daughters in any detail because she worries about their feelings. “I wouldn’t want them to feel anxious over the fact that they’re children of A-bomb survivors,” she said. She recalls that when her younger daughter was a child, the girl was physically weak, and Ms. Miyoshi sometimes thought, “I shouldn’t have had her.”

Now, thinking about how she survived for so long, she believes that her mother, who didn’t want to die, has helped keep her alive. I sensed the deep affection and concern she feels for her mother and her daughters. (Rie Nii)

(Originally published on September 11, 2012)