Toshiyuki Miyake, 82, Minami Ward

Nov. 2, 2012

Haunted by thoughts of dead schoolmates

A-bomb account in English conveys cruelty to the world

“I wonder what determines a person’s fate, whether they live or die. We were all in the same place when the bomb exploded. When I think of the regrets my classmates must have felt, in dying that day, I get choked up.” Toshiyuki Miyake, 82, was 15 years old when the atomic bomb was dropped on August 6, 1945. He returned to the place where he experienced the bombing with his peers, and revived his memories.

At the time, he was a third-year student at Hiroshima Municipal First Technical School (now Hiroshima Prefectural Technical High School). Because his parents and his four younger siblings were in China, where his father was working, Mr. Miyake lived with his grandparents in the Nihocho district (part of present-day Minami Ward).

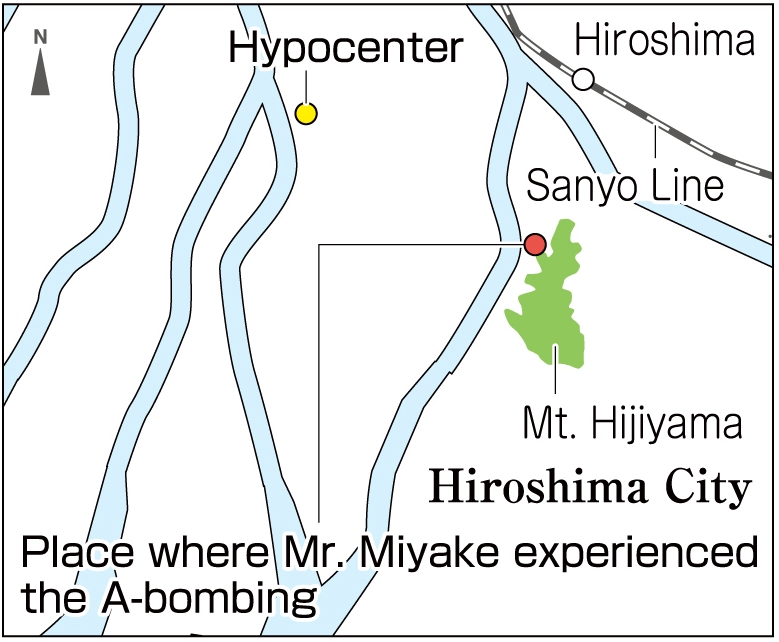

When the atomic bomb fell, he was en route to a work site where he would help create a fire lane in the event of air raids. He was walking along with about 20 classmates at the foot of Mt. Hijiyama, on the western side, roughly 1.7 kilometers from the hypocenter. Suddenly there was a flash, and then everything went dark. The blast blew him off the ground, to a spot about 20 meters away. When he took in his surroundings, he found himself in a dugout designed for air raids.

He spotted a friend who had been walking with him just moments before—the friend was now pinned under a wall. He and other classmates went to the boy’s aid, but he was already dead.

The only students who fled to Mt. Hijiyama were those still able to walk. Though Mr. Miyake suffered burns to the right side of his body, he managed to flee with the others. At the top of the small mountain, names were called and some of his classmates were missing.

Later, he heard that some students who had made it up the mountain and then returned home, ultimately died while crying out, “Water! Give me water!”

Mr. Miyake walked back to his house from Mt. Hijiyama. The cap he was wearing had protected his head from the bomb’s heat rays, but from below his ear down to his leg, his skin was burned. He tried every remedy for burns that others told him might be effective, such as washing his body with sea water. He even swallowed his feelings of sympathy for the victims, gathered the bones of cremated bodies from a schoolyard, and ground them into powder to apply to his burns.

After some time, the burned skin healed. Autumn came and he returned to school, reuniting with old classmates. “It’s good that you survived!” they said, amid hugs and tears.

Even now, when he recalls his friends who perished in the atomic bombing, his eyes fill with tears. In 2009, he organized a memorial service for his departed schoolmates—the first formal ceremony he pursued—at a temple in Minami Ward. “They were on my mind for such a long time. Holding that memorial service eased my feelings a little bit,” he said.

His eldest son has lived in Switzerland for many years, where he works in banking. “In order to abolish nuclear weapons and create a world where human beings can be happy, I want people to know about the cruelty of the atomic bombing,” he said, explaining how he provided his son with the account of his A-bomb experience in English to share with others. (Sakiko Masuda, Staff Writer)

Hiroshima Municipal First Technical School: Preserving a list of 53 victims

Hiroshima Municipal First Technical School was founded in 1939. At the time of the atomic bombing, the school was located in Shinonomecho (part of present-day Minami Ward) and there were three courses of study: mechanical engineering, electrical engineering, and industrial chemistry.

In 1945, Toshiyuki Miyake, 82, was in his third year at the school. “Many of the boys hoped to work at a munitions factory or transformer substation in the future,” he recalled.

Following the war, in 1948, the school was discontinued and Hiroshima Municipal Technical High School was established. Then, in 1949, the institution underwent, in conjunction with other schools, a sweeping reorganization and was renamed Minami High School. Ultimately, it was succeeded by Hiroshima Prefectural Technical High School, located in Deshio, Minami Ward.

The office of the alumni association has faithfully preserved a copy of the list of students who died in the atomic bombing. The list includes the names of 50 students and three teachers who perished while helping to create fire lanes in Kakomachi and Tsurumicho (both part of present-day Naka Ward), to prepare for possible air strikes, or working in munitions factories. It is likely, however, that the death toll from the school was even higher.

Teenagers’ Impressions

The cruelty of the atomic bombing

Mr. Miyake said that he hasn’t even shared his account of the atomic bombing with his children. Thinking about his schoolmates who died that day makes him so choked up with pain. His friends right near him were killed in an instant. This has left a scar in his mind that remains to this day. I thought again of the great cruelty of the atomic bombing. (Daichi Ishii, 16)

Desire grows for nuclear abolition

“I hope you’ll do what you can to create a world without nuclear weapons and war.” When Mr. Miyake, who experienced the suffering of the atomic bomb firsthand, said that to us, it strengthened my desire to help abolish nuclear weapons.

I’d like to start by listening to the accounts of atomic bomb survivors and reading books on the atomic bombing, in order to deepen my thoughts on peace, and then share these thoughts with others. (Risa Murakosi, 16)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

After suffering severe burns, Mr. Miyake ground down the bones from cremated bodies and applied the powder to his wounds. While gathering these remains, he was holding a set of Buddhist prayer beads in his hand and praying to the dead, “Please forgive me. Please help me.”

Susumu Amato, another A-bomb survivor whose story appeared in this newspaper last February, recalled that he mixed bone meal, normally used as fertilizer, with oil and rubbed this concoction onto his burned skin. Such accounts illustrate how the survivors’ desire to live made them turn to any method that they thought might help.

In aftermath of the atomic bombing, there was a shortage of medical supplies in Hiroshima, so people resorted to all kinds of home remedies. Another example comes from someone who continually drank water brewed with “lizard’s tail,” a medicinal herb, to combat symptoms of nosebleed and hair loss. It was also believed that Japanese mugwort and the leaves of the camphor tree could help relieve bleeding and high fever. These home remedies demonstrate how people were groping for ways to treat the survivors. (Sakiko Masuda)

(Originally published on October 22, 2012)

A-bomb account in English conveys cruelty to the world

“I wonder what determines a person’s fate, whether they live or die. We were all in the same place when the bomb exploded. When I think of the regrets my classmates must have felt, in dying that day, I get choked up.” Toshiyuki Miyake, 82, was 15 years old when the atomic bomb was dropped on August 6, 1945. He returned to the place where he experienced the bombing with his peers, and revived his memories.

At the time, he was a third-year student at Hiroshima Municipal First Technical School (now Hiroshima Prefectural Technical High School). Because his parents and his four younger siblings were in China, where his father was working, Mr. Miyake lived with his grandparents in the Nihocho district (part of present-day Minami Ward).

When the atomic bomb fell, he was en route to a work site where he would help create a fire lane in the event of air raids. He was walking along with about 20 classmates at the foot of Mt. Hijiyama, on the western side, roughly 1.7 kilometers from the hypocenter. Suddenly there was a flash, and then everything went dark. The blast blew him off the ground, to a spot about 20 meters away. When he took in his surroundings, he found himself in a dugout designed for air raids.

He spotted a friend who had been walking with him just moments before—the friend was now pinned under a wall. He and other classmates went to the boy’s aid, but he was already dead.

The only students who fled to Mt. Hijiyama were those still able to walk. Though Mr. Miyake suffered burns to the right side of his body, he managed to flee with the others. At the top of the small mountain, names were called and some of his classmates were missing.

Later, he heard that some students who had made it up the mountain and then returned home, ultimately died while crying out, “Water! Give me water!”

Mr. Miyake walked back to his house from Mt. Hijiyama. The cap he was wearing had protected his head from the bomb’s heat rays, but from below his ear down to his leg, his skin was burned. He tried every remedy for burns that others told him might be effective, such as washing his body with sea water. He even swallowed his feelings of sympathy for the victims, gathered the bones of cremated bodies from a schoolyard, and ground them into powder to apply to his burns.

After some time, the burned skin healed. Autumn came and he returned to school, reuniting with old classmates. “It’s good that you survived!” they said, amid hugs and tears.

Even now, when he recalls his friends who perished in the atomic bombing, his eyes fill with tears. In 2009, he organized a memorial service for his departed schoolmates—the first formal ceremony he pursued—at a temple in Minami Ward. “They were on my mind for such a long time. Holding that memorial service eased my feelings a little bit,” he said.

His eldest son has lived in Switzerland for many years, where he works in banking. “In order to abolish nuclear weapons and create a world where human beings can be happy, I want people to know about the cruelty of the atomic bombing,” he said, explaining how he provided his son with the account of his A-bomb experience in English to share with others. (Sakiko Masuda, Staff Writer)

Hiroshima Insight

Hiroshima Municipal First Technical School: Preserving a list of 53 victims

Hiroshima Municipal First Technical School was founded in 1939. At the time of the atomic bombing, the school was located in Shinonomecho (part of present-day Minami Ward) and there were three courses of study: mechanical engineering, electrical engineering, and industrial chemistry.

In 1945, Toshiyuki Miyake, 82, was in his third year at the school. “Many of the boys hoped to work at a munitions factory or transformer substation in the future,” he recalled.

Following the war, in 1948, the school was discontinued and Hiroshima Municipal Technical High School was established. Then, in 1949, the institution underwent, in conjunction with other schools, a sweeping reorganization and was renamed Minami High School. Ultimately, it was succeeded by Hiroshima Prefectural Technical High School, located in Deshio, Minami Ward.

The office of the alumni association has faithfully preserved a copy of the list of students who died in the atomic bombing. The list includes the names of 50 students and three teachers who perished while helping to create fire lanes in Kakomachi and Tsurumicho (both part of present-day Naka Ward), to prepare for possible air strikes, or working in munitions factories. It is likely, however, that the death toll from the school was even higher.

Teenagers’ Impressions

The cruelty of the atomic bombing

Mr. Miyake said that he hasn’t even shared his account of the atomic bombing with his children. Thinking about his schoolmates who died that day makes him so choked up with pain. His friends right near him were killed in an instant. This has left a scar in his mind that remains to this day. I thought again of the great cruelty of the atomic bombing. (Daichi Ishii, 16)

Desire grows for nuclear abolition

“I hope you’ll do what you can to create a world without nuclear weapons and war.” When Mr. Miyake, who experienced the suffering of the atomic bomb firsthand, said that to us, it strengthened my desire to help abolish nuclear weapons.

I’d like to start by listening to the accounts of atomic bomb survivors and reading books on the atomic bombing, in order to deepen my thoughts on peace, and then share these thoughts with others. (Risa Murakosi, 16)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

After suffering severe burns, Mr. Miyake ground down the bones from cremated bodies and applied the powder to his wounds. While gathering these remains, he was holding a set of Buddhist prayer beads in his hand and praying to the dead, “Please forgive me. Please help me.”

Susumu Amato, another A-bomb survivor whose story appeared in this newspaper last February, recalled that he mixed bone meal, normally used as fertilizer, with oil and rubbed this concoction onto his burned skin. Such accounts illustrate how the survivors’ desire to live made them turn to any method that they thought might help.

In aftermath of the atomic bombing, there was a shortage of medical supplies in Hiroshima, so people resorted to all kinds of home remedies. Another example comes from someone who continually drank water brewed with “lizard’s tail,” a medicinal herb, to combat symptoms of nosebleed and hair loss. It was also believed that Japanese mugwort and the leaves of the camphor tree could help relieve bleeding and high fever. These home remedies demonstrate how people were groping for ways to treat the survivors. (Sakiko Masuda)

(Originally published on October 22, 2012)