Hideo Kimura, 80, Nishi Ward, Hiroshima

Feb. 26, 2013

Conveying a “hell on earth” through picture story shows

Hopes children long remember how towns and bodies are burned in war

Hideo Kimura, 80, creates “picture story shows” based on the atomic bombing and presents these at kindergartens and elementary schools. With the skin on his neck and arms scarred from burns, he continues to convey the message, to the next generation, that the hell on earth he experienced must never be repeated.

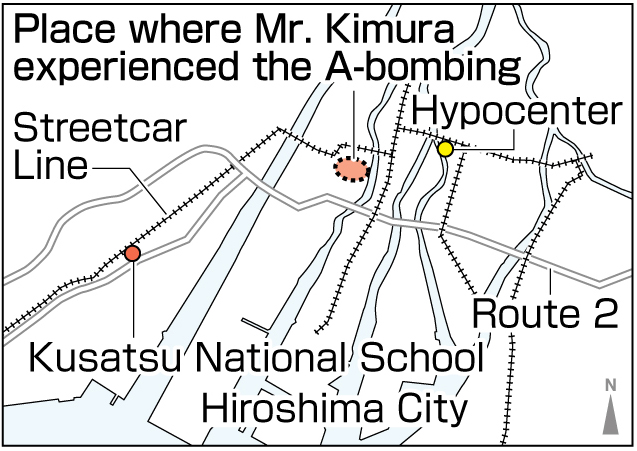

In 1945, he was 12 years old, in his first year at Kusatsu National Advanced School (now Kusatsu Elementary School in Nishi Ward, Hiroshima). On the morning of August 6, after helping his father, a fisherman, with his work, he went off to school, where students were gathering before heading to the Koamicho area (part of present-day Naka Ward) to join in creating a fire lane by tearing down buildings.

Taking part in the work were 167 students from the school, including Mr. Kimura, all in pants, white short-sleeved shirts, and straw hats on their heads. As they were walking along a river bank around the Kannon area (in today’s Nishi Ward, about 1.2 to 1.7 kilometers from the hypocenter), three B-29 bombers buzzed overhead. One of the planes dropped something shiny, and then he saw a great flash, followed by darkness.

He crouched down, covering his head with his arms. Seconds later, he was engulfed in burning heat. He and his friends weren’t sure where to go, so they decided to return to school. He then realized that he had lost the straw sandals that had been on his feet prior to the blast.

At an irrigation ditch in Takasu (now part of Nishi Ward), he stopped to wash himself, and the skin on his face peeled right off. The skin on his arms, too, was dangling down from his flesh.

A few days after the bombing, he suffered hair loss and vomiting. He recalled, “I was worried every day, thinking I would die, so I couldn’t sleep.” It took more than six months for the burns on his face, neck, and arms to heal. Even then, the new layer of skin was so tight he could no longer hold a baseball. When his grip was too strong, the skin would tear and bleed. Three to five years later, the scarring from his burns rose like “beef steak” and became keloids.

Around ten years ago, after turning 70, he began drawing scenes of his A-bomb experience when Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and other organizations put out a call for pictures of the atomic bombing. Mr. Kimura’s work has been met with appreciation, with a painting he did on porcelain appearing at Saioji Temple in Nakajimacho, Naka Ward.

Around 2007, he started making his picture story shows based on the atomic bombing. To date, he has created seven stories about nuclear weapons and war, conveying not only his own A-bomb experience, but also the experience of his brother, who was five years older than him and died in the blast while at Hirose National School (in today’s Naka Ward), and the local Volunteer Army Corps. The theme of his seventh story, now in progress, is the outbreak of a third world war.

“When there is war, towns and bodies are burned, and children are separated from their parents—you would be all alone. For these reasons, we must never have war,” Mr. Kimura said. He conveys this message while presenting his picture story shows. He hopes that when the children are grown, they will remember the words of the picture-story-show man. (Rie Nii, Staff Writer)

National schools promoted militarism

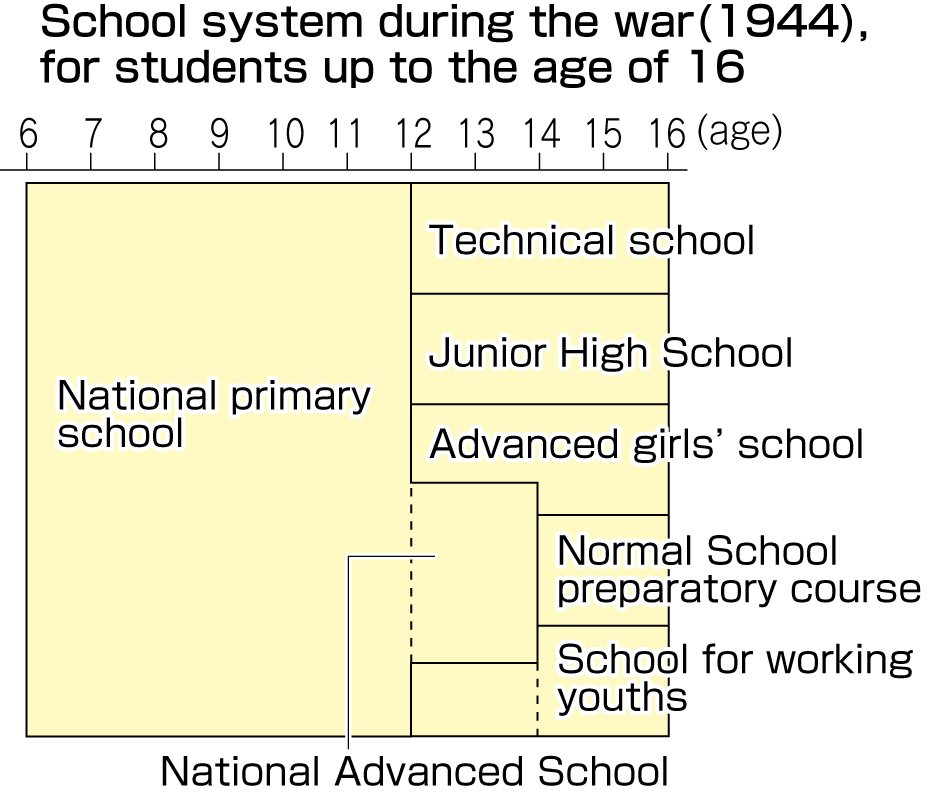

Elementary schools today were called “national primary schools” during the war. In 1941, a “National School Order” was issued, which made changes to the nation’s school system. Elementary schools became national primary schools, both covering the first six years of education, and advanced elementary schools (two or three years) became national advanced schools (two years).

The “National School Order” heightened the militarism of Japanese schools. Hideo Kimura, 80, of Nishi Ward, Hiroshima, attended both types of schools, the regular elementary school and the national primary school. Looking back at his time in the latter school, he said he was taught that Japanese soldiers from the imperial army and navy went off to war and sacrificed their lives for the good of the nation.

After studying six years at national primary school, children studied at a national advanced school or middle school (junior high school, advanced girls’ school, or technical school).

In 1947, after the war had ended, the Basic Act of Education and School Education Act were established, instituting the current system of education which consists of six years of elementary school and three years of junior high school.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Deaths should not be in vain

“The tragedy of the atomic bombing should never be repeated,” Mr. Kimura told us. In order to convey his strong message to children, he makes pictures of the atomic bombing. Although he hesitates to depict such cruel scenes, he continues his work so that the victims will not have died in vain. Seeing his determination, I felt we have a duty to help hand down the thoughts of the A-bomb survivors. (Kanna Inoue, 17)

Life changed into three colors

His pictures which depict life before the atomic bombing show lots of vivid colors, like the green grass and trees and blue sky. After the bombing, however, mainly three color are used—black, gray, and red—and there are many faces of people crying and shouting. I realized that peace can be expressed through the use of color.

One day we won’t be able to listen to the accounts of the bombing directly from the survivors. Mr. Kimura’s pictures will then play an important role in conveying the cruelty of the atomic bombing. (Yumi Kimura, 16)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

“It was hell on earth.” This is something I’ve heard over and over from atomic bomb survivors. Although I understand what they mean, I don’t think I can truly comprehend it. Hideo Kimura explained, “People right in front of me were dying, one after the other. They were pleading for help, but no help could be given. They all died sad deaths. It was like hell itself.” He added, “When there is war, towns and bodies are burned, and children are separated from their parents—you’d be all alone. For these reasons, we must never have war.” He used plain, heartfelt language to help us understand his experience.

I think he’s able to use such clear language because he himself suffered the misery of the bombing. If you have the opportunity, I urge you to watch one of Mr. Kimura’s picture story shows and listen to his A-bomb account. In this way, your imagination may touch the devastating consequences of the atomic bombing. (Rie Nii)

(Originally published on February 11, 2013)

Hopes children long remember how towns and bodies are burned in war

Hideo Kimura, 80, creates “picture story shows” based on the atomic bombing and presents these at kindergartens and elementary schools. With the skin on his neck and arms scarred from burns, he continues to convey the message, to the next generation, that the hell on earth he experienced must never be repeated.

In 1945, he was 12 years old, in his first year at Kusatsu National Advanced School (now Kusatsu Elementary School in Nishi Ward, Hiroshima). On the morning of August 6, after helping his father, a fisherman, with his work, he went off to school, where students were gathering before heading to the Koamicho area (part of present-day Naka Ward) to join in creating a fire lane by tearing down buildings.

Taking part in the work were 167 students from the school, including Mr. Kimura, all in pants, white short-sleeved shirts, and straw hats on their heads. As they were walking along a river bank around the Kannon area (in today’s Nishi Ward, about 1.2 to 1.7 kilometers from the hypocenter), three B-29 bombers buzzed overhead. One of the planes dropped something shiny, and then he saw a great flash, followed by darkness.

He crouched down, covering his head with his arms. Seconds later, he was engulfed in burning heat. He and his friends weren’t sure where to go, so they decided to return to school. He then realized that he had lost the straw sandals that had been on his feet prior to the blast.

At an irrigation ditch in Takasu (now part of Nishi Ward), he stopped to wash himself, and the skin on his face peeled right off. The skin on his arms, too, was dangling down from his flesh.

A few days after the bombing, he suffered hair loss and vomiting. He recalled, “I was worried every day, thinking I would die, so I couldn’t sleep.” It took more than six months for the burns on his face, neck, and arms to heal. Even then, the new layer of skin was so tight he could no longer hold a baseball. When his grip was too strong, the skin would tear and bleed. Three to five years later, the scarring from his burns rose like “beef steak” and became keloids.

Around ten years ago, after turning 70, he began drawing scenes of his A-bomb experience when Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and other organizations put out a call for pictures of the atomic bombing. Mr. Kimura’s work has been met with appreciation, with a painting he did on porcelain appearing at Saioji Temple in Nakajimacho, Naka Ward.

Around 2007, he started making his picture story shows based on the atomic bombing. To date, he has created seven stories about nuclear weapons and war, conveying not only his own A-bomb experience, but also the experience of his brother, who was five years older than him and died in the blast while at Hirose National School (in today’s Naka Ward), and the local Volunteer Army Corps. The theme of his seventh story, now in progress, is the outbreak of a third world war.

“When there is war, towns and bodies are burned, and children are separated from their parents—you would be all alone. For these reasons, we must never have war,” Mr. Kimura said. He conveys this message while presenting his picture story shows. He hopes that when the children are grown, they will remember the words of the picture-story-show man. (Rie Nii, Staff Writer)

Hiroshima Insight

National schools promoted militarism

Elementary schools today were called “national primary schools” during the war. In 1941, a “National School Order” was issued, which made changes to the nation’s school system. Elementary schools became national primary schools, both covering the first six years of education, and advanced elementary schools (two or three years) became national advanced schools (two years).

The “National School Order” heightened the militarism of Japanese schools. Hideo Kimura, 80, of Nishi Ward, Hiroshima, attended both types of schools, the regular elementary school and the national primary school. Looking back at his time in the latter school, he said he was taught that Japanese soldiers from the imperial army and navy went off to war and sacrificed their lives for the good of the nation.

After studying six years at national primary school, children studied at a national advanced school or middle school (junior high school, advanced girls’ school, or technical school).

In 1947, after the war had ended, the Basic Act of Education and School Education Act were established, instituting the current system of education which consists of six years of elementary school and three years of junior high school.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Deaths should not be in vain

“The tragedy of the atomic bombing should never be repeated,” Mr. Kimura told us. In order to convey his strong message to children, he makes pictures of the atomic bombing. Although he hesitates to depict such cruel scenes, he continues his work so that the victims will not have died in vain. Seeing his determination, I felt we have a duty to help hand down the thoughts of the A-bomb survivors. (Kanna Inoue, 17)

Life changed into three colors

His pictures which depict life before the atomic bombing show lots of vivid colors, like the green grass and trees and blue sky. After the bombing, however, mainly three color are used—black, gray, and red—and there are many faces of people crying and shouting. I realized that peace can be expressed through the use of color.

One day we won’t be able to listen to the accounts of the bombing directly from the survivors. Mr. Kimura’s pictures will then play an important role in conveying the cruelty of the atomic bombing. (Yumi Kimura, 16)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

“It was hell on earth.” This is something I’ve heard over and over from atomic bomb survivors. Although I understand what they mean, I don’t think I can truly comprehend it. Hideo Kimura explained, “People right in front of me were dying, one after the other. They were pleading for help, but no help could be given. They all died sad deaths. It was like hell itself.” He added, “When there is war, towns and bodies are burned, and children are separated from their parents—you’d be all alone. For these reasons, we must never have war.” He used plain, heartfelt language to help us understand his experience.

I think he’s able to use such clear language because he himself suffered the misery of the bombing. If you have the opportunity, I urge you to watch one of Mr. Kimura’s picture story shows and listen to his A-bomb account. In this way, your imagination may touch the devastating consequences of the atomic bombing. (Rie Nii)

(Originally published on February 11, 2013)