Teruko Ueno, 83, Nishi Ward, Hiroshima

May 29, 2013

Carried a large man to safety from his hospital bed

Nursed the wounded day and night in the aftermath

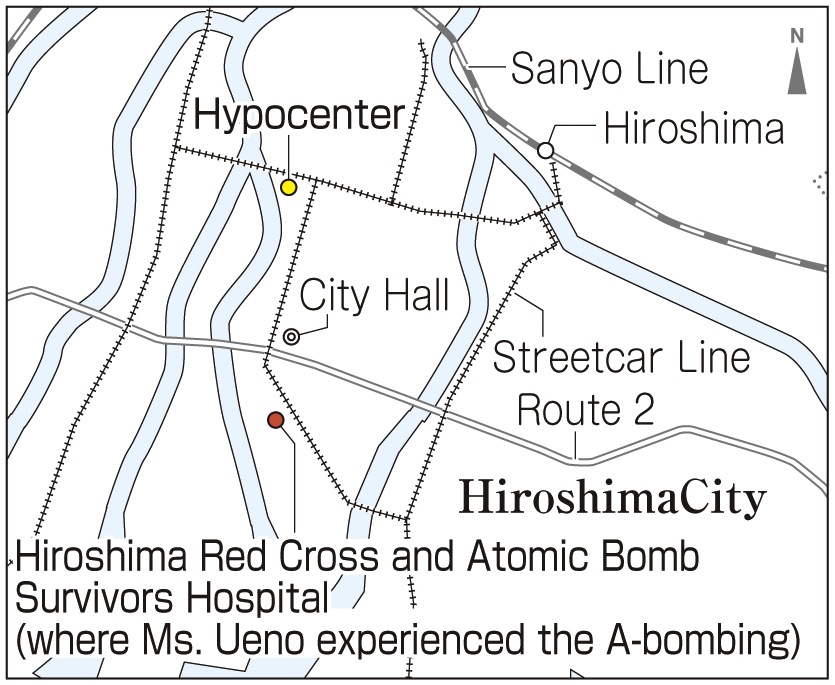

On August 6, 1945, when the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Teruko Ueno (nee Morimoto) was in her second year in a nursing program at Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital, located in Sendamachi, about 1.6 kilometers from the hypocenter. Her dormitory on the grounds, a wooden structure, was destroyed by the blast and caught fire. She tried to aid fellow students, but they died in front of her, crushed by fallen beams or killed in the flames.

At 8:15 that morning, Ms. Ueno was making a liquid meal for a student who was suffering from dysentery. She had just been outside to check on silverware being sterilized in boiling water and was returning to the kitchen, through a passageway, when she saw a flash in the sky and things began tumbling down. She quickly dove under the table where she was cooking.

When her surroundings had grown quiet, she opened her eyes and saw a ray of light through the wreckage. She then realized she was level with the fallen roof of the two-story building. Her clothes were now in tatters, and some red dirt was smeared on her head, but she was uninjured.

When the dormitory caught fire, she joined the effort to extinguish the flames, passing buckets of water from one person to the next, but the building, and its inhabitants, couldn’t be saved. As sparks rained down on the main building of the hospital, too, they sought to prevent the fire from spreading by beating it back with broom-like implements.

Checking the surgical ward on the first floor of the main building, where she was assigned, Ms. Ueno came across a patient, a soldier, who was unable to flee due to a spinal condition. She put the big soldier on her back, while lugging a special bed equipped with a tortoise-shell-like cast in her arms, and evacuated him from the building. Looking back on the incident, she said, “It was an emergency so I had a lot more strength than usual.”

As a token of gratitude, the man gave her a bag for soldiers which contained a towel and a pair of geta (traditional Japanese clogs). “The towel was really useful in those days, when it was hard to find something to wipe your face with,” she recalled.

The burn victims quickly overwhelmed the hospital and the building became so crowded that there was no room to maneuver. The dead were carried to a cremation site where the Hiroshima Blood Center for Japan’s Red Cross now stands.

She has no memory of what she ate or where she slept during that first week following the bombing. She worked day and night to help with the relief efforts, with little rest or sleep. She remembers, though, that a cow strayed onto the hospital grounds and was butchered for its meat, and she received some.

About three days after the bombing, her father came for her from her parents’ home in the village of Sagotani (part of present-day Saeki Ward). But she was so busy with her nursing work that they had only a short conversation, her father asking if she was okay and Ms. Ueno responding, “Yes, don’t worry about me.”

In 1946, the next year, she graduated from the nursing program and went on to work in the surgical ward at Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital. She assisted with operations involving skin grafts, where a patient’s skin from the thigh was grafted to an area that had developed a keloid scar as a result of burns, among other types of operations.

To date, she has experienced no serious illness, and has three children, seven grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren. Still, on the occasion of every equinox [when Buddhist traditions are observed] and August 6, the anniversary of the atomic bombing, she visits the memorial standing in the front of the hospital, as well as the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims in Peace Memorial Park, to offer water to the souls of those who died in thirst. (Rie Nii, Staff Writer)

Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital: Endured through the postwar period

Today’s Hiroshima Red Cross and Atomic Bomb Survivors Hospital, located in Naka Ward, was founded in 1939 as the Japan Red Cross Hiroshima Branch Hospital. The hospital then established the training program for nurses which Ms. Ueno entered. In 1943, the name of the hospital was changed to Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital. During the war, it was a designated military hospital which accepted ordinary citizens as outpatients, but only military personnel could be hospitalized there.

At the time of the atomic bombing, it is estimated that 554 people were working at the hospital, including doctors, nurses, and nursing students. There were 250 inpatients as well. The atomic bomb killed 56 staff members and inpatients, and another roughly 360 people were injured on the grounds, some slightly and others more seriously.

Scores of victims, wounded in the A-bomb attack, converged on the hospital for aid. The doctors, nurses, nursing students, and inpatients—everyone who was capable of pitching in to help—became engaged in the relief efforts. Their medical supplies, though, soon ran out.

Because the hospital was made of concrete, the main building didn’t collapse or burn, although it suffered warped window frames and shattered panes of glass, among other damage. The building endured for nearly half a century until, in 1993, a new building was constructed and the aging one demolished. The iron frames of windows that had been bent by the force of the blast were moved to another location, then preserved as part of the memorial which now stands in front of the hospital.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Compassion for others is important

I was moved by how Ms. Ueno, in her bare feet, could carry a soldier to safety from his hospital room, through the debris and pieces of glass.

I was impressed, too, how the soldier gave gifts to her, a pair of geta and a towel, at a time when such goods were in short supply. Their compassion for each other teaches us that it’s important to care about others as we live our lives. (Arata Kono, 15)

Improve the social standing of care givers

Ms. Ueno told us that, in the aftermath of the atomic bombing, she was working so hard without much rest that she had no energy to enjoy the reunion with her father. I think there are many people, like Ms. Ueno, who work as nurses or care givers, carrying out their duties in a spirit of self-sacrifice. In Japan, however, their social standing isn’t high enough; it doesn’t match the level of their efforts. In my opinion, steps should be taken to improve this situation. (Yuka Ichimura, 16)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

After the war, Allied soldiers visited Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital. Although others received chocolate and candies from the soldiers, Ms. Ueno was afraid and refused the gifts. However, when a soldier wanted an abacus and a pair of chopsticks, she agreed to “exchange” them for some chocolate. It was the first time she tried chocolate and was delighted by the sweet, wonderful taste.

As for the United States, Ms. Ueno admits that “Even now, I don’t like the country very much.” When shopping, she prefers to buy things made in Europe over similar items from the United States. She confesses to having mixed feelings toward the country, though, saying, “In fact, I’ve been there for sightseeing.” (Rie Nii)

(Originally published in March 11, 2013)

Nursed the wounded day and night in the aftermath

On August 6, 1945, when the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Teruko Ueno (nee Morimoto) was in her second year in a nursing program at Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital, located in Sendamachi, about 1.6 kilometers from the hypocenter. Her dormitory on the grounds, a wooden structure, was destroyed by the blast and caught fire. She tried to aid fellow students, but they died in front of her, crushed by fallen beams or killed in the flames.

At 8:15 that morning, Ms. Ueno was making a liquid meal for a student who was suffering from dysentery. She had just been outside to check on silverware being sterilized in boiling water and was returning to the kitchen, through a passageway, when she saw a flash in the sky and things began tumbling down. She quickly dove under the table where she was cooking.

When her surroundings had grown quiet, she opened her eyes and saw a ray of light through the wreckage. She then realized she was level with the fallen roof of the two-story building. Her clothes were now in tatters, and some red dirt was smeared on her head, but she was uninjured.

When the dormitory caught fire, she joined the effort to extinguish the flames, passing buckets of water from one person to the next, but the building, and its inhabitants, couldn’t be saved. As sparks rained down on the main building of the hospital, too, they sought to prevent the fire from spreading by beating it back with broom-like implements.

Checking the surgical ward on the first floor of the main building, where she was assigned, Ms. Ueno came across a patient, a soldier, who was unable to flee due to a spinal condition. She put the big soldier on her back, while lugging a special bed equipped with a tortoise-shell-like cast in her arms, and evacuated him from the building. Looking back on the incident, she said, “It was an emergency so I had a lot more strength than usual.”

As a token of gratitude, the man gave her a bag for soldiers which contained a towel and a pair of geta (traditional Japanese clogs). “The towel was really useful in those days, when it was hard to find something to wipe your face with,” she recalled.

The burn victims quickly overwhelmed the hospital and the building became so crowded that there was no room to maneuver. The dead were carried to a cremation site where the Hiroshima Blood Center for Japan’s Red Cross now stands.

She has no memory of what she ate or where she slept during that first week following the bombing. She worked day and night to help with the relief efforts, with little rest or sleep. She remembers, though, that a cow strayed onto the hospital grounds and was butchered for its meat, and she received some.

About three days after the bombing, her father came for her from her parents’ home in the village of Sagotani (part of present-day Saeki Ward). But she was so busy with her nursing work that they had only a short conversation, her father asking if she was okay and Ms. Ueno responding, “Yes, don’t worry about me.”

In 1946, the next year, she graduated from the nursing program and went on to work in the surgical ward at Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital. She assisted with operations involving skin grafts, where a patient’s skin from the thigh was grafted to an area that had developed a keloid scar as a result of burns, among other types of operations.

To date, she has experienced no serious illness, and has three children, seven grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren. Still, on the occasion of every equinox [when Buddhist traditions are observed] and August 6, the anniversary of the atomic bombing, she visits the memorial standing in the front of the hospital, as well as the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims in Peace Memorial Park, to offer water to the souls of those who died in thirst. (Rie Nii, Staff Writer)

Hiroshima Insight

Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital: Endured through the postwar period

Today’s Hiroshima Red Cross and Atomic Bomb Survivors Hospital, located in Naka Ward, was founded in 1939 as the Japan Red Cross Hiroshima Branch Hospital. The hospital then established the training program for nurses which Ms. Ueno entered. In 1943, the name of the hospital was changed to Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital. During the war, it was a designated military hospital which accepted ordinary citizens as outpatients, but only military personnel could be hospitalized there.

At the time of the atomic bombing, it is estimated that 554 people were working at the hospital, including doctors, nurses, and nursing students. There were 250 inpatients as well. The atomic bomb killed 56 staff members and inpatients, and another roughly 360 people were injured on the grounds, some slightly and others more seriously.

Scores of victims, wounded in the A-bomb attack, converged on the hospital for aid. The doctors, nurses, nursing students, and inpatients—everyone who was capable of pitching in to help—became engaged in the relief efforts. Their medical supplies, though, soon ran out.

Because the hospital was made of concrete, the main building didn’t collapse or burn, although it suffered warped window frames and shattered panes of glass, among other damage. The building endured for nearly half a century until, in 1993, a new building was constructed and the aging one demolished. The iron frames of windows that had been bent by the force of the blast were moved to another location, then preserved as part of the memorial which now stands in front of the hospital.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Compassion for others is important

I was moved by how Ms. Ueno, in her bare feet, could carry a soldier to safety from his hospital room, through the debris and pieces of glass.

I was impressed, too, how the soldier gave gifts to her, a pair of geta and a towel, at a time when such goods were in short supply. Their compassion for each other teaches us that it’s important to care about others as we live our lives. (Arata Kono, 15)

Improve the social standing of care givers

Ms. Ueno told us that, in the aftermath of the atomic bombing, she was working so hard without much rest that she had no energy to enjoy the reunion with her father. I think there are many people, like Ms. Ueno, who work as nurses or care givers, carrying out their duties in a spirit of self-sacrifice. In Japan, however, their social standing isn’t high enough; it doesn’t match the level of their efforts. In my opinion, steps should be taken to improve this situation. (Yuka Ichimura, 16)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

After the war, Allied soldiers visited Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital. Although others received chocolate and candies from the soldiers, Ms. Ueno was afraid and refused the gifts. However, when a soldier wanted an abacus and a pair of chopsticks, she agreed to “exchange” them for some chocolate. It was the first time she tried chocolate and was delighted by the sweet, wonderful taste.

As for the United States, Ms. Ueno admits that “Even now, I don’t like the country very much.” When shopping, she prefers to buy things made in Europe over similar items from the United States. She confesses to having mixed feelings toward the country, though, saying, “In fact, I’ve been there for sightseeing.” (Rie Nii)

(Originally published in March 11, 2013)