Kiyoshi Fujii, 84, Aki Ward, Hiroshima

May 30, 2013

Suffers nightmares of victims he couldn’t return to their families

Hopes to appeal for nuclear abolition until the age of 100

Kiyoshi Fujii, now 84, was 16 years old at the time of the atomic bombing, and searched for relatives through the ruins of Hiroshima for about a month in the aftermath of the blast. The memories of coming upon the bodies of a classmate and a former teacher are seared into his mind. At the time, however, he was unable to help return their remains to the families. Even now, after the passing of nearly 68 years, he sometimes suffers nightmares which involve this experience.

Mr. Fujii was born in Tokyo, but after his parents passed away, he came to Hiroshima, where a number of relatives lived. In March of 1945, he graduated from First Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High School (now Kokutaiji High School) and was mobilized to work at a munitions factory.

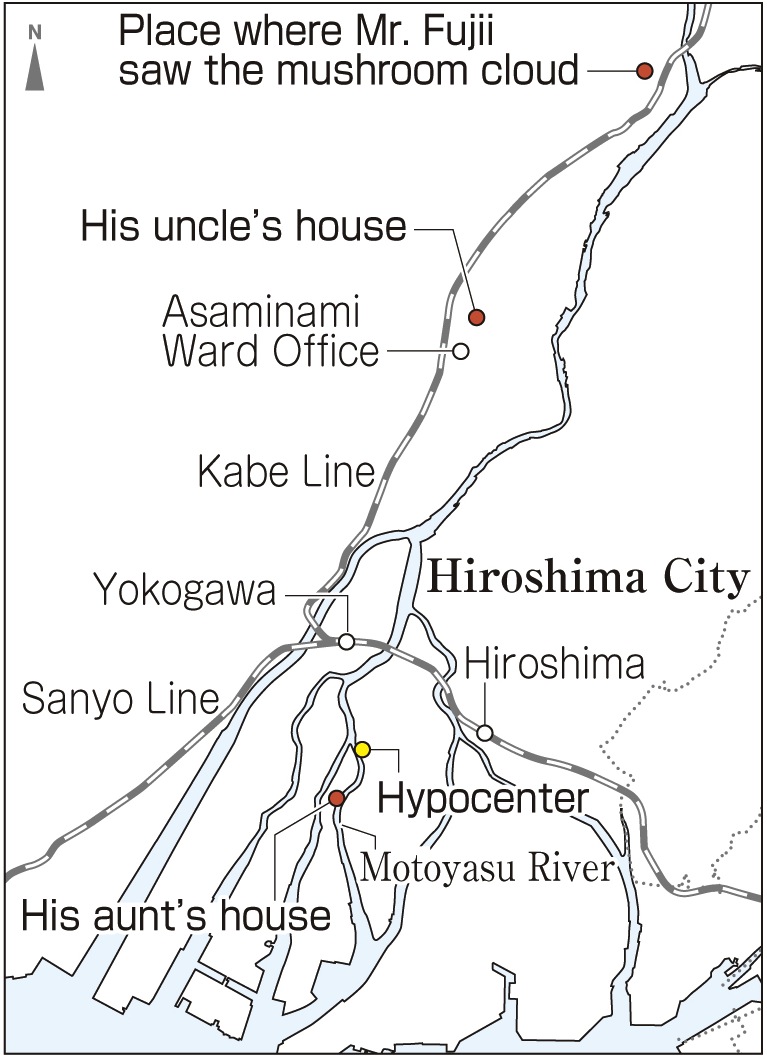

Because he was planning to enter Yamaguchi College of Economics (today, the Faculty of Economics at Yamaguchi University) on August 10, he had left the dormitory of his junior high at the end of July and was living at his aunt’s house--also an inn--in Kakomachi (now part of Naka Ward), located about 900 meters from the hypocenter.

When he heard the news that a factory at the Iwakuni Army Fuel Depot (in Yamaguchi Prefecture), where he would be mobilized to work while in college, had been hit by an air raid, he became worried, thinking he might die there. Wanting to say goodbye to relatives and close friends, in case he didn’t survive, on the evening of August 5 he visited his uncle, who was the mayor of Furuichi Town (part of present-day Asaminami Ward).

The next morning, August 6, he left his uncle’s house and rode his bike north to meet a friend. Suddenly, he heard a loud boom. When he looked back, he saw a mushroom-shaped cloud rising in the sky. He then hurried back to his uncle’s house.

To search for his uncle’s second son, Mr. Fujii headed to central Hiroshima. But he wasn’t able to reach the downtown area because of the roaring fire. The next day, August 7, he returned and went to Kakomachi. His aunt’s house had burned to the ground. And the Motoyasu River, which flows nearby, was choked with bodies. He looked for his cousin, his aunt’s eldest daughter, who had gone to the prefectural office on the morning of August 6 to help dismantle buildings to create a fire lane. But he was unable to locate her.

Mr. Fujii found his uncle’s son, however, at the former Hiroshima Municipal First Girls’ High School (now Funairi High School), where he had been working. Mr. Fujii brought him back to his uncle’s house on a bicycle-drawn cart.

After August 8, Mr. Fujii continued to search for his missing cousin. He looked for her among the bodies laying on the ground, and visited evacuation centers and hospitals to gain some kind of clue. But in the end, he was unable to find even a stitch of her clothing.

He now believes that she lies in Peace Memorial Park, beneath the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound, where the ashes of unidentified victims have been placed.

After the war, Mr. Fujii was employed at a bank and pursued other lines of work. He hopes to live until the age of 100, when his great-grandchild turns 20. “The mission of my life is appealing for the abolition of nuclear weapons,” he said. He belongs to a group which creates picture-story shows and gives performances for children. He urges others to “Start with what you’re capable of to help make the world a more peaceful place, such as taking part in a campaign to collect signatures in support of the abolition of nuclear weapons.” (Sakiko Masuda, Staff Writer)

Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound holds remains of 70,000 victims

Beneath the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park are the remains of approximately 70,000 victims of the atomic bombing. The identities of most of the victims are unknown, but the remains of 816 people have been identified, yet have not been claimed.

The Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound was first created in 1946, the year after the bombing, at nearly the same location as the current mound, which was built in 1955. During the process of reconstructing the city, the remains of many victims were unearthed at the construction sites of roads and buildings, and these remains were taken, one after another, to the mound. Recently, in 2005, remains discovered on Ninoshima Island, where many of the wounded were ferried in the aftermath of the bombing, were placed in the mound, too.

When it comes to the remains that have been identified, the City of Hiroshima disseminates a list of names to the public in order to seek family members of the victims. Every few months, the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Department in City Hall apparently receives a couple of inquiries from people who are searching for clues as to the whereabouts of a family member.

Kaoru Osugi, a section head at the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Department, said, “We hope to swiftly return the remains of victims currently at rest in the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound to their families. Please contact us if you are looking for a loved one.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

The atomic bombing damaged hearts, too

Mr. Fujii told us that he came across the bodies of a friend and a former teacher, but he was unable to do anything for them at the time. Since then, he has blamed himself for this, and even today, more than 60 years later, he suffers nightmares because of this experience.

I realized clearly that the atomic bombing not only damaged people’s bodies, it damaged their hearts deeply, too. (Nene Takahashi, 17)

Resolve problems through dialogue

“Radiation is dreadful,” Mr. Fujii told us. “I hope you will do something to help abolish nuclear weapons.” Having experienced radiation-related illness himself, which increases the number of white blood cells, Mr. Fujii has strong feelings about nuclear arms.

As he said, in daily life we have to keep in mind that problems should be resolved through dialogue, not force, and go on making efforts to realize the abolition of nuclear weapons. (Yuji Iguchi, 15)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

A monument to newspaper workers who were victims of the A-bomb stands along the Honkawa River in the Kakomachi area of Naka Ward. Along with the words “renouncing war,” the names of victims are inscribed on the plate. At the top of the list is the name “Aiko Aikawa”--she was a cousin of Mr. Fujii.

At the time, Ms. Aikawa was six years older than Mr. Fujii and she was employed at the Chugoku Shimbun. During dinner on August 5, the evening before the bombing, she told him that she would be mobilized to work the next morning at the Hiroshima Prefectural building, helping to create a fire lane in the event of air raids. Mr. Fujii said to her, “It’ll probably be hot working under the sun. Don’t overdo it.” These were the last words they shared.

Mr. Fujii searched for Ms. Aikawa for about a month in the aftermath of the A-bomb attack. As a consequence of walking around the city center, he suffered damaging radiation exposure.

A total of 114 employees of the Chugoku Shimbun died as a result of the atomic bombing. Despite this devastation, the surviving staff made tremendous efforts to resume publishing, and only three days after the blast, they succeeded, with the actual printing of the newspapers carried out by the Asahi Shimbun and Mainichi Shimbun newspaper companies. (Sakiko Masuda)

(Originally published on March 25, 2013)

Hopes to appeal for nuclear abolition until the age of 100

Kiyoshi Fujii, now 84, was 16 years old at the time of the atomic bombing, and searched for relatives through the ruins of Hiroshima for about a month in the aftermath of the blast. The memories of coming upon the bodies of a classmate and a former teacher are seared into his mind. At the time, however, he was unable to help return their remains to the families. Even now, after the passing of nearly 68 years, he sometimes suffers nightmares which involve this experience.

Mr. Fujii was born in Tokyo, but after his parents passed away, he came to Hiroshima, where a number of relatives lived. In March of 1945, he graduated from First Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High School (now Kokutaiji High School) and was mobilized to work at a munitions factory.

Because he was planning to enter Yamaguchi College of Economics (today, the Faculty of Economics at Yamaguchi University) on August 10, he had left the dormitory of his junior high at the end of July and was living at his aunt’s house--also an inn--in Kakomachi (now part of Naka Ward), located about 900 meters from the hypocenter.

When he heard the news that a factory at the Iwakuni Army Fuel Depot (in Yamaguchi Prefecture), where he would be mobilized to work while in college, had been hit by an air raid, he became worried, thinking he might die there. Wanting to say goodbye to relatives and close friends, in case he didn’t survive, on the evening of August 5 he visited his uncle, who was the mayor of Furuichi Town (part of present-day Asaminami Ward).

The next morning, August 6, he left his uncle’s house and rode his bike north to meet a friend. Suddenly, he heard a loud boom. When he looked back, he saw a mushroom-shaped cloud rising in the sky. He then hurried back to his uncle’s house.

To search for his uncle’s second son, Mr. Fujii headed to central Hiroshima. But he wasn’t able to reach the downtown area because of the roaring fire. The next day, August 7, he returned and went to Kakomachi. His aunt’s house had burned to the ground. And the Motoyasu River, which flows nearby, was choked with bodies. He looked for his cousin, his aunt’s eldest daughter, who had gone to the prefectural office on the morning of August 6 to help dismantle buildings to create a fire lane. But he was unable to locate her.

Mr. Fujii found his uncle’s son, however, at the former Hiroshima Municipal First Girls’ High School (now Funairi High School), where he had been working. Mr. Fujii brought him back to his uncle’s house on a bicycle-drawn cart.

After August 8, Mr. Fujii continued to search for his missing cousin. He looked for her among the bodies laying on the ground, and visited evacuation centers and hospitals to gain some kind of clue. But in the end, he was unable to find even a stitch of her clothing.

He now believes that she lies in Peace Memorial Park, beneath the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound, where the ashes of unidentified victims have been placed.

After the war, Mr. Fujii was employed at a bank and pursued other lines of work. He hopes to live until the age of 100, when his great-grandchild turns 20. “The mission of my life is appealing for the abolition of nuclear weapons,” he said. He belongs to a group which creates picture-story shows and gives performances for children. He urges others to “Start with what you’re capable of to help make the world a more peaceful place, such as taking part in a campaign to collect signatures in support of the abolition of nuclear weapons.” (Sakiko Masuda, Staff Writer)

Hiroshima Insight

Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound holds remains of 70,000 victims

Beneath the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park are the remains of approximately 70,000 victims of the atomic bombing. The identities of most of the victims are unknown, but the remains of 816 people have been identified, yet have not been claimed.

The Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound was first created in 1946, the year after the bombing, at nearly the same location as the current mound, which was built in 1955. During the process of reconstructing the city, the remains of many victims were unearthed at the construction sites of roads and buildings, and these remains were taken, one after another, to the mound. Recently, in 2005, remains discovered on Ninoshima Island, where many of the wounded were ferried in the aftermath of the bombing, were placed in the mound, too.

When it comes to the remains that have been identified, the City of Hiroshima disseminates a list of names to the public in order to seek family members of the victims. Every few months, the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Department in City Hall apparently receives a couple of inquiries from people who are searching for clues as to the whereabouts of a family member.

Kaoru Osugi, a section head at the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Department, said, “We hope to swiftly return the remains of victims currently at rest in the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound to their families. Please contact us if you are looking for a loved one.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

The atomic bombing damaged hearts, too

Mr. Fujii told us that he came across the bodies of a friend and a former teacher, but he was unable to do anything for them at the time. Since then, he has blamed himself for this, and even today, more than 60 years later, he suffers nightmares because of this experience.

I realized clearly that the atomic bombing not only damaged people’s bodies, it damaged their hearts deeply, too. (Nene Takahashi, 17)

Resolve problems through dialogue

“Radiation is dreadful,” Mr. Fujii told us. “I hope you will do something to help abolish nuclear weapons.” Having experienced radiation-related illness himself, which increases the number of white blood cells, Mr. Fujii has strong feelings about nuclear arms.

As he said, in daily life we have to keep in mind that problems should be resolved through dialogue, not force, and go on making efforts to realize the abolition of nuclear weapons. (Yuji Iguchi, 15)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

A monument to newspaper workers who were victims of the A-bomb stands along the Honkawa River in the Kakomachi area of Naka Ward. Along with the words “renouncing war,” the names of victims are inscribed on the plate. At the top of the list is the name “Aiko Aikawa”--she was a cousin of Mr. Fujii.

At the time, Ms. Aikawa was six years older than Mr. Fujii and she was employed at the Chugoku Shimbun. During dinner on August 5, the evening before the bombing, she told him that she would be mobilized to work the next morning at the Hiroshima Prefectural building, helping to create a fire lane in the event of air raids. Mr. Fujii said to her, “It’ll probably be hot working under the sun. Don’t overdo it.” These were the last words they shared.

Mr. Fujii searched for Ms. Aikawa for about a month in the aftermath of the A-bomb attack. As a consequence of walking around the city center, he suffered damaging radiation exposure.

A total of 114 employees of the Chugoku Shimbun died as a result of the atomic bombing. Despite this devastation, the surviving staff made tremendous efforts to resume publishing, and only three days after the blast, they succeeded, with the actual printing of the newspapers carried out by the Asahi Shimbun and Mainichi Shimbun newspaper companies. (Sakiko Masuda)

(Originally published on March 25, 2013)