Isao Miura, 86, Naka Ward, Hiroshima

May 30, 2013

Shocked at sight of the flattened city

Radiation exposure leads to deaths of younger brother and relatives

On August 10, 1945, four days after the atomic bombing, Isao Miura, 86, returned to Hiroshima from the city of Amagasaki, in Hyogo Prefecture, where he had been mobilized to work for the war effort alongside other students. The Hiroshima he found was “totally flattened.” The ruins of the city, he said, looked completely different from the burnt fields he had seen in Nagoya and Osaka as a result of incendiary bombing in those cities.

Mr. Miura graduated from Shudo Junior High School in March of 1944. He was 17 at the time. In junior high school, he had belonged to the mountaineering club. During the war, mountaineering wasn’t freely permitted, but as “training” for the war, members of the club, wearing their school uniforms, were able to climb various mountains in Hiroshima Prefecture.

During school hours, students took part in “military drills,” learning how to shoot guns or setting out on hikes of more than 40 kilometers with guns in their hands and heavy stone-filled packs on their backs. This was a time when people were unable to speak out freely.

After graduating from junior high school, Mr. Miura entered Nagoya Pharmaceutical College (now Nagoya City University). When he became a second-year student in the spring of 1945, he was mobilized to work at a factory in Amagasaki, run by a pharmaceutical company that was headquartered in Osaka. At the factory he was involved in producing the ingredients for making mustard gas, a chemical weapon.

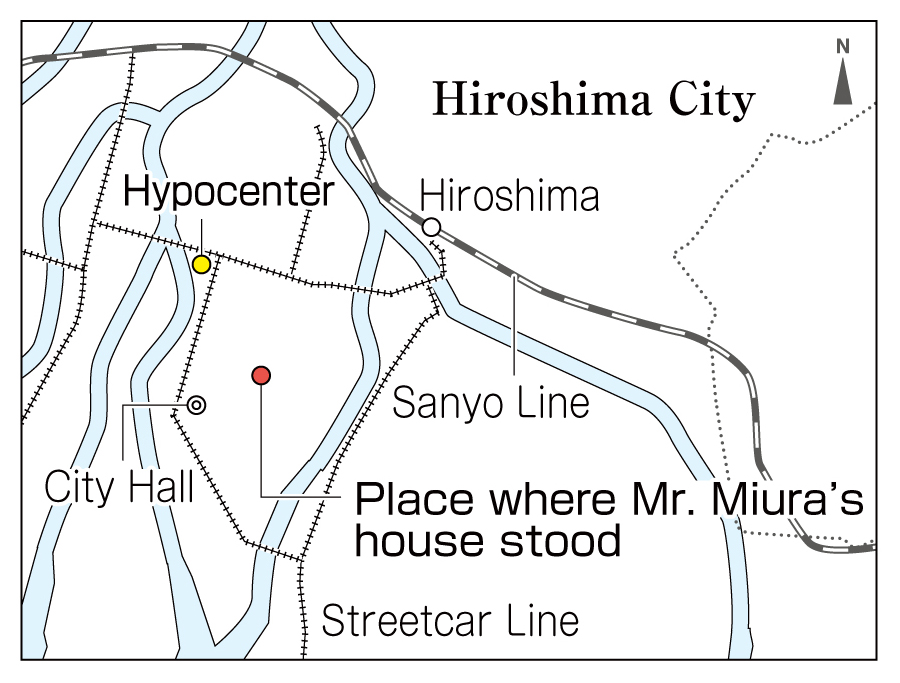

Also in the spring of 1945, his family evacuated from their home in Fujimicho (part of today’s Naka Ward, about 900 meters from the hypocenter), where Mr. Miura had lived since he was a small child, to Nakano Village (part of present-day Aki Ward). Thanks to this decision, they were able to escape the direct impact of the atomic bomb. However, in their place, his father’s hiking buddy, Yutaka Ito, along with three members of his family who were staying at the house in Fujimicho, were killed by the blast.

After the atomic bombing, Mr. Miura returned to Hiroshima and stood before the ruins of his family’s home. The site was flattened, without even charred remains from the structure, like beams, that were left behind in typical air raids. He recalls how the stench of death was even more terrible than the burnt smell. Yutaka Ito was able to flee to a relatives’ house in the village of Inokuchi (part of today’s Nishi Ward), and passed away there, but at the house in Fujimicho, Mr. Miura and his mother, Katsuko, collected the remains of Mr. Ito’s wife and one child. The remains of another child were never found.

Two days after the atomic bomb was dropped, Mr. Miura’s brother, Atsushi, who was five years younger, went to check on their house in Fujimicho. Fifteen years later, in June of 1960, he died of leukemia. Subsequently, Mr. Miura’s relatives, who had also entered the city center and were exposed to the bomb’s residual radiation, passed away one after the other. Mr. Miura was shocked by this series of deaths, considering 15 years had already passed since the A-bomb attack.

He knows that his own radiation exposure has damaged his body, and he watches his health closely each day. He chooses what he eats with care, and avoids snacks between meals.

Mr. Miura hopes that the younger generation will learn about the time before the war and the war itself. Though the current Japanese government is pursuing an economic recovery by raising prices, they are also considering changes to the constitution and strengthening the nation’s military might. “These conditions are similar to Japan before the war,” he said. Then he added, stressing his words, “War brings hardship to everyone. I want you to understand how pointless it is.” (Rie Nii, Staff Writer)

Incendiary bomb: Wooden buildings burned in air raids

Because Hiroshima was considered a possible target for the atomic bomb, the city was spared the heavy air raids suffered by other places during the war. Not only large cities like Tokyo and Osaka, but also Hiroshima-area cities like Fukuyama, Kure, and Tokuyama bore the brunt of indiscriminate attacks, which produced great numbers of civilian deaths.

In air raids, the M-69 Incendiary Cluster Bomb was often used. This bomb was designed to burn down Japan’s wooden buildings.

The hexagonal-shaped bomb was about 50 centimeters long, about 7 centimeters in diameter, and weighed 2.8 kilograms. Lurking inside was a type of petroleum jelly called napalm. At one end of the bomb was an explosive charge, and when the bomb struck the roof of a building, or the ground, the napalm ignited and fire quickly spread.

The velocity of the bomb’s drop was carefully controlled, with the detonator on the bottom and four strips of cloth, each about 1 meter long, fluttering at the other end.

Bundles of 38 of these bombs were dropped onto Japanese cities from American B-29 bombers.

The city of Nagaoka in Niigata Prefecture was attacked with incendiary bombs on the night of August 1, 1945, and even today, the bombs used in this air raid are discovered beneath the ground.

Teenagers’ Impressions

I want to convey the accounts of war

Because food supplies dwindled during the war, almost everything was rationed and people suffered from a lack of food. Today we’re not engaged in a war, and we have an abundance of food and goods, but Mr. Miura told us that the policy of the current Japanese government reminds him of what the government was doing prior to World War II.At the site where his house once stood, Mr. Miura looks back on the atomic bombing.

To engage the interest of people who don’t have peace issues on their minds, I want to share with them the experiences of war that I’ve heard from the atomic bomb survivors and convey the horror of war. (Takeshi Iwata, 14)

War is exhausting for minds and bodies

Mr. Miura experienced a number of air raids and heard the sound of the air raid siren at all hours of the day and night. Once, the burning oil from an incendiary bomb splattered onto his face, and when he tried to wipe it away, the fire spread. He even saw a classmate burn to death in such conditions. War is exhausting for the minds and bodies of human beings. I want to tell others about the horror and terror of war so that war will not be fought again. (Saya Teranishi, 16)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

Mr. Miura submitted his application for the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate in December 2011, and received it in June 2012. One reason he didn’t apply prior to December 2011 was because he hadn’t yet suffered any serious illness, but even more than that, he felt guilty because he hadn’t taken part in the A-bomb survivors’ movement. Receiving the certificate, when he made no contribution to the movement, stirred feelings of shame. Apart from his family, this interview was the first time he had ever shared his A-bomb experience.

After suffering a stroke in January 2012, he has lingering disabilities, including difficulty walking. Still, because of the sense of danger he feels from current conditions in Japan, which he likens to the situation in the days before the war, he wanted to share his experience and his thoughts with the junior writers. We should pay careful heed to Mr. Miura’s words. (Rie Nii)

(Originally published on April 8, 2013)

Radiation exposure leads to deaths of younger brother and relatives

On August 10, 1945, four days after the atomic bombing, Isao Miura, 86, returned to Hiroshima from the city of Amagasaki, in Hyogo Prefecture, where he had been mobilized to work for the war effort alongside other students. The Hiroshima he found was “totally flattened.” The ruins of the city, he said, looked completely different from the burnt fields he had seen in Nagoya and Osaka as a result of incendiary bombing in those cities.

Mr. Miura graduated from Shudo Junior High School in March of 1944. He was 17 at the time. In junior high school, he had belonged to the mountaineering club. During the war, mountaineering wasn’t freely permitted, but as “training” for the war, members of the club, wearing their school uniforms, were able to climb various mountains in Hiroshima Prefecture.

During school hours, students took part in “military drills,” learning how to shoot guns or setting out on hikes of more than 40 kilometers with guns in their hands and heavy stone-filled packs on their backs. This was a time when people were unable to speak out freely.

After graduating from junior high school, Mr. Miura entered Nagoya Pharmaceutical College (now Nagoya City University). When he became a second-year student in the spring of 1945, he was mobilized to work at a factory in Amagasaki, run by a pharmaceutical company that was headquartered in Osaka. At the factory he was involved in producing the ingredients for making mustard gas, a chemical weapon.

Also in the spring of 1945, his family evacuated from their home in Fujimicho (part of today’s Naka Ward, about 900 meters from the hypocenter), where Mr. Miura had lived since he was a small child, to Nakano Village (part of present-day Aki Ward). Thanks to this decision, they were able to escape the direct impact of the atomic bomb. However, in their place, his father’s hiking buddy, Yutaka Ito, along with three members of his family who were staying at the house in Fujimicho, were killed by the blast.

After the atomic bombing, Mr. Miura returned to Hiroshima and stood before the ruins of his family’s home. The site was flattened, without even charred remains from the structure, like beams, that were left behind in typical air raids. He recalls how the stench of death was even more terrible than the burnt smell. Yutaka Ito was able to flee to a relatives’ house in the village of Inokuchi (part of today’s Nishi Ward), and passed away there, but at the house in Fujimicho, Mr. Miura and his mother, Katsuko, collected the remains of Mr. Ito’s wife and one child. The remains of another child were never found.

Two days after the atomic bomb was dropped, Mr. Miura’s brother, Atsushi, who was five years younger, went to check on their house in Fujimicho. Fifteen years later, in June of 1960, he died of leukemia. Subsequently, Mr. Miura’s relatives, who had also entered the city center and were exposed to the bomb’s residual radiation, passed away one after the other. Mr. Miura was shocked by this series of deaths, considering 15 years had already passed since the A-bomb attack.

He knows that his own radiation exposure has damaged his body, and he watches his health closely each day. He chooses what he eats with care, and avoids snacks between meals.

Mr. Miura hopes that the younger generation will learn about the time before the war and the war itself. Though the current Japanese government is pursuing an economic recovery by raising prices, they are also considering changes to the constitution and strengthening the nation’s military might. “These conditions are similar to Japan before the war,” he said. Then he added, stressing his words, “War brings hardship to everyone. I want you to understand how pointless it is.” (Rie Nii, Staff Writer)

Hiroshima Insight

Incendiary bomb: Wooden buildings burned in air raids

Because Hiroshima was considered a possible target for the atomic bomb, the city was spared the heavy air raids suffered by other places during the war. Not only large cities like Tokyo and Osaka, but also Hiroshima-area cities like Fukuyama, Kure, and Tokuyama bore the brunt of indiscriminate attacks, which produced great numbers of civilian deaths.

In air raids, the M-69 Incendiary Cluster Bomb was often used. This bomb was designed to burn down Japan’s wooden buildings.

The hexagonal-shaped bomb was about 50 centimeters long, about 7 centimeters in diameter, and weighed 2.8 kilograms. Lurking inside was a type of petroleum jelly called napalm. At one end of the bomb was an explosive charge, and when the bomb struck the roof of a building, or the ground, the napalm ignited and fire quickly spread.

The velocity of the bomb’s drop was carefully controlled, with the detonator on the bottom and four strips of cloth, each about 1 meter long, fluttering at the other end.

Bundles of 38 of these bombs were dropped onto Japanese cities from American B-29 bombers.

The city of Nagaoka in Niigata Prefecture was attacked with incendiary bombs on the night of August 1, 1945, and even today, the bombs used in this air raid are discovered beneath the ground.

Teenagers’ Impressions

I want to convey the accounts of war

Because food supplies dwindled during the war, almost everything was rationed and people suffered from a lack of food. Today we’re not engaged in a war, and we have an abundance of food and goods, but Mr. Miura told us that the policy of the current Japanese government reminds him of what the government was doing prior to World War II.At the site where his house once stood, Mr. Miura looks back on the atomic bombing.

To engage the interest of people who don’t have peace issues on their minds, I want to share with them the experiences of war that I’ve heard from the atomic bomb survivors and convey the horror of war. (Takeshi Iwata, 14)

War is exhausting for minds and bodies

Mr. Miura experienced a number of air raids and heard the sound of the air raid siren at all hours of the day and night. Once, the burning oil from an incendiary bomb splattered onto his face, and when he tried to wipe it away, the fire spread. He even saw a classmate burn to death in such conditions. War is exhausting for the minds and bodies of human beings. I want to tell others about the horror and terror of war so that war will not be fought again. (Saya Teranishi, 16)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

Mr. Miura submitted his application for the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate in December 2011, and received it in June 2012. One reason he didn’t apply prior to December 2011 was because he hadn’t yet suffered any serious illness, but even more than that, he felt guilty because he hadn’t taken part in the A-bomb survivors’ movement. Receiving the certificate, when he made no contribution to the movement, stirred feelings of shame. Apart from his family, this interview was the first time he had ever shared his A-bomb experience.

After suffering a stroke in January 2012, he has lingering disabilities, including difficulty walking. Still, because of the sense of danger he feels from current conditions in Japan, which he likens to the situation in the days before the war, he wanted to share his experience and his thoughts with the junior writers. We should pay careful heed to Mr. Miura’s words. (Rie Nii)

(Originally published on April 8, 2013)