Hanako Senkawa, 86, Higashihiroshima City

Jun. 4, 2013

Living a full life for the sake of friends who were never found

The streets of homes and shops that she saw the day before had disappeared. Only smoke rose from the flattened ground at Hiroshima Station (in today’s Minami Ward). For two days, she wandered about, searching for friends and the doctor at the hospital where she had been working. But she was unable to locate anyone.

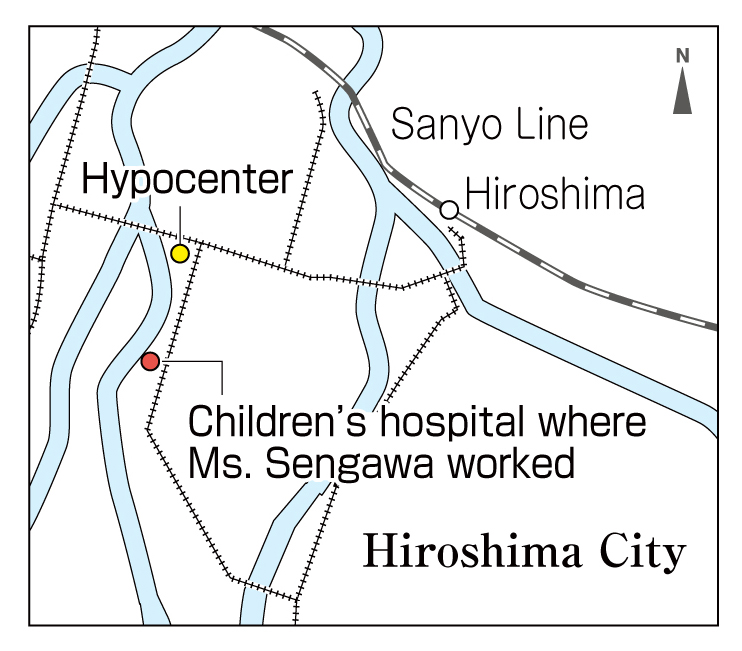

At the time, Hanako Senkawa, now 86, was working as a nurse at a children’s hospital in Otemachi (part of today’s Naka Ward, about 700 meters from the hypocenter) and living at the facility. Starting in September 1945, she was scheduled to undergo training as a military nurse at Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital and she needed a futon [a Japanese-style mattress]. In this regard, she wanted to speak with her mother Hisako, and so she planned to return to her parents’ house in the village of Yoshitomi (in present-day Higashihiroshima City) after work on the evening of August 5.

But she boarded the wrong train, on the Geibi Line, by mistake and had to spend the night on the platform at Mukaibara Station (in present-day Akitakata City). On August 6, she took the first train back to Hiroshima Station and, around 8 a.m., she boarded a train on the Sanyo Line and left Hiroshima Station.

When the train passed Seno Station (in today’s Aki Ward), her ears began to ring. Some passengers were shouting, “A bomb was dropped somewhere!” She looked up at the sky and saw three American B-29 bombers flying toward the city of Kure.

As soon as she arrived at Saijo Station (in today’s Higashihiroshima City), she raced home. Her mother and younger brother Satoshi, 13, were surprised to see her, and welcomed her. They had been working in the fields when, at 8:15 that morning, Satoshi, whose back was toward Hiroshima, suddenly cried out, feeling a wave of heat, and they saw a mushroom cloud rise into the sky. Later, when the fire department announced that Hiroshima had been destroyed, they were going to head to Hiroshima to search for Ms. Senkawa.

The next day, August 7, Ms. Senkawa boarded a train bound for Hiroshima. However, the train stopped at Mukainada Station (in today’s Fuchu Town) and could go no farther. So she got off the train and walked along the railroad tracks to Hiroshima Station.

Her hospital had disappeared without a trace. Only a scorched iron bathtub, that had retained its shape, told her where the building had once stood. She was unable to find her four coworkers and the doctor who she believed had been working at the hospital or were supporting the war effort by helping to dismantle buildings to create fire lanes. She wandered about the city center then went to an evacuation center in Fuchu Town, where the doctor’s parents’ house was located.

That day she returned to Higashihiroshima, then on August 8 she came to Hiroshima again. She checked inside several streetcars, which had come to a halt because of the bombing. There were many skeletons in the trains, but she didn’t come across any of the people she was searching for.

After the war, she worked as a nurse at several hospitals, including the National Hiroshima Sanatorium (currently, the National Hospital Organization Higashihiroshima Medical Center) and Saijo Central Hospital. She retired from nursing this past January. “I could go on living for the sake of my friends and the doctor,” Ms. Sengawa said. “This is why I’ve tried my best to live a full life.” (Rie Nii, Staff Writer)

B-29 Superfortress flew farther and higher

The American planes which departed from Tinian Island, near Saipan in the Pacific Ocean, and dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were B-29 bombers. This type of bomber was used in many attacks on Japanese cities during World War II.

The development of the B-29 by the United States began in 1939. Compared to all the bombers that had come before it, the B-29 had the ability to fly longer distances and at higher altitudes. Thus, it was dubbed the “Superfortress.”

In order to attack the Japanese mainland, the United States deployed B-29s in Chengdu, China. In June 1944, these B-29s attacked northern Kyushu for the first time. Still, though the aircraft was able to fly as far as Kyushu, it couldn’t reach Tokyo or Osaka. As a result, the United States built bases on islands in the Pacific Ocean, including Saipan, Guam, and Tinian.

From these locations, the B-29s could then reach eastern Japan, too, and from November 1944, the United States began attacking factories in the Tokyo, Osaka, and Nagoya areas. More indiscriminate attacks were launched in March 1945, with U.S. incendiary bombs raining down on a score of Japanese cities. In Japan, the term “B-29” become synonymous with “air raid.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

I want to convey her strong will to live

Ms. Senkawa believes it was “fate” that enabled her to escape a direct experience of the atomic bombing. She added, “I want to live for the sake of my friends.” From these words, I felt her strong sense of responsibility for her life and for the lives of others.

These days, some students end up committing suicide because they’re being bullied. I want to convey Ms. Senkawa’s strong will to go on living to more and more people. (Shino Taniguchi, 14)

Cries for water show the cruel reality

Ms. Senkawa told us that people’s cries for water, every time they heard the sound of footsteps, still linger in her ears even to this day. This made me see the cruel reality of the situation in Hiroshima after the atomic bombing.

I thought, we have to build a peaceful world so that nuclear weapons will never be used again. (Yuri Ryokai, 15)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

Ms. Senkawa walked around the city of Hiroshima for two days, on August 7 and 8, 1945, in the immediate aftermath of the atomic bombing. She wonders, with concern, how much radiation from the bomb she was exposed to back then. This now weighs on her mind because of the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant in March 2011. Following the accident, the level of radiation in each area in the vicinity was reported by the media. “I’d like to know what the difference is between those levels and the level of radiation in Hiroshima after the bombing,” she said.

She had shared her account of the bombing with other nurses in the past, but this interview was the first time she talked about it with junior high and high school students. “War and the atomic bombs stole young people’s lives,” she said. “I want the young people of today to understand how dreadful war is and that war should never, ever be waged again.” She hopes the countries of the world will help each other in friendship, instead of thinking only about the growth of their own nation. (Rie Nii, Staff Writer)

(Originally published on May 13, 2013)

The streets of homes and shops that she saw the day before had disappeared. Only smoke rose from the flattened ground at Hiroshima Station (in today’s Minami Ward). For two days, she wandered about, searching for friends and the doctor at the hospital where she had been working. But she was unable to locate anyone.

At the time, Hanako Senkawa, now 86, was working as a nurse at a children’s hospital in Otemachi (part of today’s Naka Ward, about 700 meters from the hypocenter) and living at the facility. Starting in September 1945, she was scheduled to undergo training as a military nurse at Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital and she needed a futon [a Japanese-style mattress]. In this regard, she wanted to speak with her mother Hisako, and so she planned to return to her parents’ house in the village of Yoshitomi (in present-day Higashihiroshima City) after work on the evening of August 5.

But she boarded the wrong train, on the Geibi Line, by mistake and had to spend the night on the platform at Mukaibara Station (in present-day Akitakata City). On August 6, she took the first train back to Hiroshima Station and, around 8 a.m., she boarded a train on the Sanyo Line and left Hiroshima Station.

When the train passed Seno Station (in today’s Aki Ward), her ears began to ring. Some passengers were shouting, “A bomb was dropped somewhere!” She looked up at the sky and saw three American B-29 bombers flying toward the city of Kure.

As soon as she arrived at Saijo Station (in today’s Higashihiroshima City), she raced home. Her mother and younger brother Satoshi, 13, were surprised to see her, and welcomed her. They had been working in the fields when, at 8:15 that morning, Satoshi, whose back was toward Hiroshima, suddenly cried out, feeling a wave of heat, and they saw a mushroom cloud rise into the sky. Later, when the fire department announced that Hiroshima had been destroyed, they were going to head to Hiroshima to search for Ms. Senkawa.

The next day, August 7, Ms. Senkawa boarded a train bound for Hiroshima. However, the train stopped at Mukainada Station (in today’s Fuchu Town) and could go no farther. So she got off the train and walked along the railroad tracks to Hiroshima Station.

Her hospital had disappeared without a trace. Only a scorched iron bathtub, that had retained its shape, told her where the building had once stood. She was unable to find her four coworkers and the doctor who she believed had been working at the hospital or were supporting the war effort by helping to dismantle buildings to create fire lanes. She wandered about the city center then went to an evacuation center in Fuchu Town, where the doctor’s parents’ house was located.

That day she returned to Higashihiroshima, then on August 8 she came to Hiroshima again. She checked inside several streetcars, which had come to a halt because of the bombing. There were many skeletons in the trains, but she didn’t come across any of the people she was searching for.

After the war, she worked as a nurse at several hospitals, including the National Hiroshima Sanatorium (currently, the National Hospital Organization Higashihiroshima Medical Center) and Saijo Central Hospital. She retired from nursing this past January. “I could go on living for the sake of my friends and the doctor,” Ms. Sengawa said. “This is why I’ve tried my best to live a full life.” (Rie Nii, Staff Writer)

Hiroshima Insight

B-29 Superfortress flew farther and higher

The American planes which departed from Tinian Island, near Saipan in the Pacific Ocean, and dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were B-29 bombers. This type of bomber was used in many attacks on Japanese cities during World War II.

The development of the B-29 by the United States began in 1939. Compared to all the bombers that had come before it, the B-29 had the ability to fly longer distances and at higher altitudes. Thus, it was dubbed the “Superfortress.”

In order to attack the Japanese mainland, the United States deployed B-29s in Chengdu, China. In June 1944, these B-29s attacked northern Kyushu for the first time. Still, though the aircraft was able to fly as far as Kyushu, it couldn’t reach Tokyo or Osaka. As a result, the United States built bases on islands in the Pacific Ocean, including Saipan, Guam, and Tinian.

From these locations, the B-29s could then reach eastern Japan, too, and from November 1944, the United States began attacking factories in the Tokyo, Osaka, and Nagoya areas. More indiscriminate attacks were launched in March 1945, with U.S. incendiary bombs raining down on a score of Japanese cities. In Japan, the term “B-29” become synonymous with “air raid.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

I want to convey her strong will to live

Ms. Senkawa believes it was “fate” that enabled her to escape a direct experience of the atomic bombing. She added, “I want to live for the sake of my friends.” From these words, I felt her strong sense of responsibility for her life and for the lives of others.

These days, some students end up committing suicide because they’re being bullied. I want to convey Ms. Senkawa’s strong will to go on living to more and more people. (Shino Taniguchi, 14)

Cries for water show the cruel reality

Ms. Senkawa told us that people’s cries for water, every time they heard the sound of footsteps, still linger in her ears even to this day. This made me see the cruel reality of the situation in Hiroshima after the atomic bombing.

I thought, we have to build a peaceful world so that nuclear weapons will never be used again. (Yuri Ryokai, 15)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

Ms. Senkawa walked around the city of Hiroshima for two days, on August 7 and 8, 1945, in the immediate aftermath of the atomic bombing. She wonders, with concern, how much radiation from the bomb she was exposed to back then. This now weighs on her mind because of the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant in March 2011. Following the accident, the level of radiation in each area in the vicinity was reported by the media. “I’d like to know what the difference is between those levels and the level of radiation in Hiroshima after the bombing,” she said.

She had shared her account of the bombing with other nurses in the past, but this interview was the first time she talked about it with junior high and high school students. “War and the atomic bombs stole young people’s lives,” she said. “I want the young people of today to understand how dreadful war is and that war should never, ever be waged again.” She hopes the countries of the world will help each other in friendship, instead of thinking only about the growth of their own nation. (Rie Nii, Staff Writer)

(Originally published on May 13, 2013)