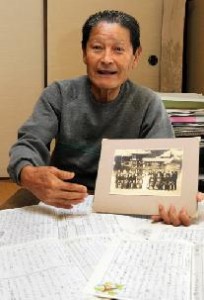

Kenji Takashina, 74, Asaminami Ward, Hiroshima

Jun. 21, 2011

Mother and friend pass away in front of his eyes

Time passes, comes to tell A-bomb account: Letters from children are "treasures"

At the beginning of our interview, Kenji Takashina, 74, shared letters he had received from elementary school students in Osaka and called them his "treasures." These students had listened to Mr. Takashina's story and then wrote such impressions as "I would be so sad if a close friend died in war" and "I'm against war." After experiencing the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Mr. Takashina lived in Osaka for about 50 years, where he was active in relating his account of the bombing.

Mr. Takashina was 8 years old when the atomic bomb was dropped. He was playing with a boy from his neighborhood near his house in the Deshio district (now, part of Minami Ward), about 2.5 kilometers from the hypocenter. He was squatting down when there was a great flash and blast. Flying fragments of glass pierced the right side of his face, from his temple to his chin.

His mother, Ayako, was at home at the time, and she was pinned under a beam and suffered multiple fractures to the bones in her upper torso. The boy Mr. Takashina had been playing with was severely injured, too, with wounds to his face and chest. With his mother and his friend, Mr. Takashina fled to his mother's cousin's house in the Kaita district. As they walked along, Mr. Takashina would help support his friend. He also gave his friend some water, which his friend gladly drank, but then the boy died in Mr. Takashina's arms.

A few days later, Mr. Takashina's mother's gums began to bleed. No treatment was available to her, though, and she died on August 13 at the age of 32. His father, Hidemaru, had already died in 1939, in a battle between Japanese soldiers and soldiers from the former Soviet Union. Mr. Takashina, now on his own and carrying an urn containing his mother’s ashes, went to his paternal grandparents’ home in the village of Toyama (now, part of Asaminami Ward), where his uncle was living.

Toyama is located 13 kilometers from the hypocenter and took in many people seeking refuge after the blast. The radioactive "black rain" which fell in the aftermath of the bombing also fell in this location. In Toyama, Mr. Takashina graduated from junior high school and began to work. While working, he sought to enter a vocational school to learn communications technology, but was unable to pass the school's health examination. At this checkup he learned for the first time that his eardrum had torn as a result of the A-bomb blast.

He passed the entrance exam for high school, but had to abandon the idea of enrolling when he wasn't able to scrape together enough money for the school expenses. He was feeling a bitterness toward life, but his mother's last words kept him going through that trying time. She had told him: "Live your life as best you can and don't cause difficulty for others."

After he turned 20, an uncle on his mother's side advised him to go to Osaka to apprentice himself in a barbershop. At the age of 26, he opened his own shop and worked there until he moved back to Hiroshima in September 2010.

About 20 years ago, prompted by his second son, an elementary school teacher, Mr. Takashina began to speak about his painful A-bomb experience. When talking in schools, he would sometimes share a letter his father had written to him. Part of it reads: "I'm going off to war. After I die, I want you to listen to your mother and grow up to be a good man. I'll always be watching over you, son."

"Our life today has been created through the sacrifices people made for their families and their nation," Mr. Takashina said. "Live as fully as you can and forge your own path for your life." (Sakiko Masuda, Staff Writer)

Brack rain: Radioactive materials fell with the rain

After the atomic bomb exploded, a huge mushroom cloud formed in the sky above the city of Hiroshima. Twenty to thirty minutes later, "black rain" began to fall. This dark-colored rain contained dust stirred up by the blast, soot from the roaring fires produced by the bomb’s heat rays, and radioactive materials emitted by the bomb.

In 1976, prompted by research conducted in the years since the bombing, the Japanese government designated the area of heavy black rainfall as the "heavy rain area." Those who were exposed to the black rain in this area are able to receive free health checkups. And in the event they develop certain diseases, such as cancer, they are eligible to obtain the Atomic Bomb Survivor's Certificate. The area of "light rain," however, is excluded from these support measures.

A survey that has been carried out by the Hiroshima city government and Hiroshima prefectural government, since 2008, has revealed that the black rain actually fell in an area about six times larger than the current "heavy rain area," and that those who were exposed to the black rain are worried about their health. The local Hiroshima governments have called on the central government to designate the entire area, including the "light rain area," as an area eligible for special support measures. The central government is now conducting its own scientific assessment of this claim.

Teenagers’ Impressions

A-bomb experience should be conveyed in other parts of Japan

I was touched by Mr. Takashina's smile when he talked about his "treasures," the letters from students he had visited. One of them wrote: "It was the first time I heard the word "pikadon," which refers to the atomic bombing." In Hiroshima, everyone knows about the atomic bombing, so I think there should be more effort made to convey information about the bombing outside of Hiroshima. (Miyu Sakata, 16)

Persevere in the face of difficulty

I was especially impressed by his words "Live as fully as you can." Even when Mr. Takashina drinks a glass of juice on a hot day, he thinks of the victims of the atomic bombing, who died before they could find a drink of water. I'm grateful that he shared his experience with us, though it's painful for him to recall, and I intend to do my best in the future when I run into difficulties of my own. (Yuni Sakata, 11)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

Mr. Takashina's father died in the Nomonhan Incident, a battle that took place in northeastern China in August 1939 between Japanese soldiers and soldiers from the former Soviet Union. Mr. Takashina was only two years old at the time. He was living in China with his family.

He has a dim memory of his father. After being wounded on the battlefield, his father was brought to a field hospital. He sat up in bed and beckoned to his son. "I think he hugged me," Mr. Takashina said. It's a happy memory that he holds onto to this day. But then his father said that he had to return to fight with the younger soldiers, ultimately dying at the age of 35.

Six years later, the atomic bomb stole away his mother, too. He had now lost both parents, but fought to go on in the years after the war ended. "You have to make your own life," he told himself, and then later to troubled boys in Osaka when he was living in that city. One reason he began sharing his A-bomb experience was due to his concern over children committing suicide.

Mr. Takashina's main message involves becoming aware of the history of the war and the importance of life. With awareness of the war fading among the public, the teenage junior writers remarked following our interview with Mr. Takashina: "I want to clearly convey the cruelty of the atomic bombing" and "If I see someone in trouble, I'll do what I can to help." Such comments were encouraging to hear. (Sakiko Masuda, Staff Writer)

(Originally published on December 13, 2011)

Time passes, comes to tell A-bomb account: Letters from children are "treasures"

At the beginning of our interview, Kenji Takashina, 74, shared letters he had received from elementary school students in Osaka and called them his "treasures." These students had listened to Mr. Takashina's story and then wrote such impressions as "I would be so sad if a close friend died in war" and "I'm against war." After experiencing the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Mr. Takashina lived in Osaka for about 50 years, where he was active in relating his account of the bombing.

Mr. Takashina was 8 years old when the atomic bomb was dropped. He was playing with a boy from his neighborhood near his house in the Deshio district (now, part of Minami Ward), about 2.5 kilometers from the hypocenter. He was squatting down when there was a great flash and blast. Flying fragments of glass pierced the right side of his face, from his temple to his chin.

His mother, Ayako, was at home at the time, and she was pinned under a beam and suffered multiple fractures to the bones in her upper torso. The boy Mr. Takashina had been playing with was severely injured, too, with wounds to his face and chest. With his mother and his friend, Mr. Takashina fled to his mother's cousin's house in the Kaita district. As they walked along, Mr. Takashina would help support his friend. He also gave his friend some water, which his friend gladly drank, but then the boy died in Mr. Takashina's arms.

A few days later, Mr. Takashina's mother's gums began to bleed. No treatment was available to her, though, and she died on August 13 at the age of 32. His father, Hidemaru, had already died in 1939, in a battle between Japanese soldiers and soldiers from the former Soviet Union. Mr. Takashina, now on his own and carrying an urn containing his mother’s ashes, went to his paternal grandparents’ home in the village of Toyama (now, part of Asaminami Ward), where his uncle was living.

Toyama is located 13 kilometers from the hypocenter and took in many people seeking refuge after the blast. The radioactive "black rain" which fell in the aftermath of the bombing also fell in this location. In Toyama, Mr. Takashina graduated from junior high school and began to work. While working, he sought to enter a vocational school to learn communications technology, but was unable to pass the school's health examination. At this checkup he learned for the first time that his eardrum had torn as a result of the A-bomb blast.

He passed the entrance exam for high school, but had to abandon the idea of enrolling when he wasn't able to scrape together enough money for the school expenses. He was feeling a bitterness toward life, but his mother's last words kept him going through that trying time. She had told him: "Live your life as best you can and don't cause difficulty for others."

After he turned 20, an uncle on his mother's side advised him to go to Osaka to apprentice himself in a barbershop. At the age of 26, he opened his own shop and worked there until he moved back to Hiroshima in September 2010.

About 20 years ago, prompted by his second son, an elementary school teacher, Mr. Takashina began to speak about his painful A-bomb experience. When talking in schools, he would sometimes share a letter his father had written to him. Part of it reads: "I'm going off to war. After I die, I want you to listen to your mother and grow up to be a good man. I'll always be watching over you, son."

"Our life today has been created through the sacrifices people made for their families and their nation," Mr. Takashina said. "Live as fully as you can and forge your own path for your life." (Sakiko Masuda, Staff Writer)

Hiroshima Insight

Brack rain: Radioactive materials fell with the rain

After the atomic bomb exploded, a huge mushroom cloud formed in the sky above the city of Hiroshima. Twenty to thirty minutes later, "black rain" began to fall. This dark-colored rain contained dust stirred up by the blast, soot from the roaring fires produced by the bomb’s heat rays, and radioactive materials emitted by the bomb.

In 1976, prompted by research conducted in the years since the bombing, the Japanese government designated the area of heavy black rainfall as the "heavy rain area." Those who were exposed to the black rain in this area are able to receive free health checkups. And in the event they develop certain diseases, such as cancer, they are eligible to obtain the Atomic Bomb Survivor's Certificate. The area of "light rain," however, is excluded from these support measures.

A survey that has been carried out by the Hiroshima city government and Hiroshima prefectural government, since 2008, has revealed that the black rain actually fell in an area about six times larger than the current "heavy rain area," and that those who were exposed to the black rain are worried about their health. The local Hiroshima governments have called on the central government to designate the entire area, including the "light rain area," as an area eligible for special support measures. The central government is now conducting its own scientific assessment of this claim.

Teenagers’ Impressions

A-bomb experience should be conveyed in other parts of Japan

I was touched by Mr. Takashina's smile when he talked about his "treasures," the letters from students he had visited. One of them wrote: "It was the first time I heard the word "pikadon," which refers to the atomic bombing." In Hiroshima, everyone knows about the atomic bombing, so I think there should be more effort made to convey information about the bombing outside of Hiroshima. (Miyu Sakata, 16)

Persevere in the face of difficulty

I was especially impressed by his words "Live as fully as you can." Even when Mr. Takashina drinks a glass of juice on a hot day, he thinks of the victims of the atomic bombing, who died before they could find a drink of water. I'm grateful that he shared his experience with us, though it's painful for him to recall, and I intend to do my best in the future when I run into difficulties of my own. (Yuni Sakata, 11)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

Mr. Takashina's father died in the Nomonhan Incident, a battle that took place in northeastern China in August 1939 between Japanese soldiers and soldiers from the former Soviet Union. Mr. Takashina was only two years old at the time. He was living in China with his family.

He has a dim memory of his father. After being wounded on the battlefield, his father was brought to a field hospital. He sat up in bed and beckoned to his son. "I think he hugged me," Mr. Takashina said. It's a happy memory that he holds onto to this day. But then his father said that he had to return to fight with the younger soldiers, ultimately dying at the age of 35.

Six years later, the atomic bomb stole away his mother, too. He had now lost both parents, but fought to go on in the years after the war ended. "You have to make your own life," he told himself, and then later to troubled boys in Osaka when he was living in that city. One reason he began sharing his A-bomb experience was due to his concern over children committing suicide.

Mr. Takashina's main message involves becoming aware of the history of the war and the importance of life. With awareness of the war fading among the public, the teenage junior writers remarked following our interview with Mr. Takashina: "I want to clearly convey the cruelty of the atomic bombing" and "If I see someone in trouble, I'll do what I can to help." Such comments were encouraging to hear. (Sakiko Masuda, Staff Writer)

(Originally published on December 13, 2011)