Yoshika Sunamoto, 82, Fuchu Town, Hiroshima

Jul. 3, 2013

Day after day he fought the disease but never lost his passion for life

After the bomb, his body was weak, but he swallowed his tears and devoted himself to work

Suddenly, a strong flash hit him from in front and to the left. He lost consciousness. When he came to, he noticed he was in the ruins of the factory next door. He had been blown there by the blast. Working desperately, he dug himself out of the debris, then pulled out three friends. One friend said, “You’re really hurt.” That was when he found he was covered with blood.

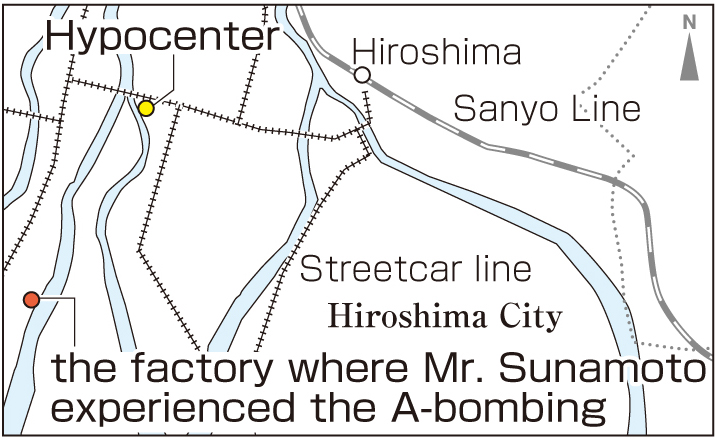

Yoshika Sunamoto, 82, was at 14 at the time of the atomic bombing. He was a third-year student at First Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High School (now Kokutaiji High School, located in Naka Ward). On August 6, 1945, he was mobilized to work in a military factory in Funairi Kawaguchi-cho (now in Naka Ward), about 2km from the hypocenter. He was working without a shirt.

The flash burned the left side of his body. His left arm suffered a gash 8cm long; he still carries the scar.

He went with some friends to Hiroshima First Municipal Girl’s School (now, Funairi High School), which served as the local evacuation center. Later, he sought treatment at an army hospital in Eba (now, Naka Ward).

However, the army hospital was full of seriously injured patients. He gave up on treatment, deciding to return to his home in Midori-machi (now, Minami Ward). His way was frequently blocked by fallen houses and fire, but getting a ride across one river in a boat and walking across another at low tide, he finally made it home.

A military doctor who was his father’s friend examined his injuries and said they would take six months to heal. That prognosis shocked him so badly he cried all night. He was afraid he would not be well in time to take the entrance examination for the Naval Academy and its Navy officer training.

The war ended, and after treatment and recuperation for a half-year, he returned to junior high school. Then, he entered Hiroshima Technical School (now the Faculty of Engineering at Hiroshima University). Anticipating progress in motorization, he joined the Auto Engineering Department. After graduation, he found a job as an engineer at an automobile retailer.

However, that summer, while training for his new job at an automobile factory in Saitama Prefecture, he was attacked by a high fever of unknown origin. A persistent temperature higher than 39 degrees forced him to return to Hiroshima.

He was unable to work for a year. “Why do I have such a weak body?” Blaming himself for not living up to his own expectations, he cried again and again in frustration.

When he did return to work, he had to battle prostate cancer and hypertensive heart disease, both certified as atomic bomb diseases. He served as president of an automobile retail company in Yamaguchi City, working there as advisor until 1998, he retired at age 67. Today he lives with his wife in Fuchu Town, Hiroshima.

His advice to youth: “Even if you fail, don’t give up. Keep working to accomplish what you set out to do.” (Sakiko Masuda, Staff Writer)

A-bomb disease Certification: The discrepancy between the judiciary and the bureaucracy

One remedy provided by the Atomic Bomb Victims’ Relief Law is a system to certify “atomic bomb diseases”. The government provides a special medical allowance (approximately 136,000 yen per month) to certified atomic bomb survivors whose diseases (cancer, leukemia, etc.) or injuries were caused by the atomic bombing and require ongoing treatment. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare certifies these atomic bomb diseases.

However, for many years the vast majority of applications were rejected. In fact, less than 1% of atomic bomb survivors were certified.

In 2003, a group of atomic bomb survivors whose applications were rejected brought a class action suit against the government in several district courts around Japan, including Hiroshima, demanding certification.

The government lost these cases one after another, so the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare revised its criteria for certification in April 2008. Since that time, the number of certifications has increased greatly.

However, a significant gap remains between the judiciary and the government agencies involved. For example, even when a court admits an atomic bomb disease, applications for certification are often rejected. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare established an expert review committee in December 2010, and the review is still underway.

Criteria for certification of atomic bomb disease

* Based on Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare documents

① Experienced atomic bombing within 3.5km of the hypocenter

② Entered within 2km of the hypocenter within 100 hours of the atomic bombing

③ Stayed for at least one week within 2km of the hypocenter within two weeks of the atomic bombing

Persons shall be certified who meet one of the three conditions above and develop one of seven diseases, including solid cancers (e.g., gastric, colorectal, breast and esophageal cancer), leukemia, hyperthyroidism and radiation cataract.

In other cases, decisions shall be made after examining a comprehensive set of factors, including level of radiation exposure.

Teenagers’ Impressions

I want to set a goal and go for it

“Go for it. Set your goal and accomplish what you set out to do,” Mr. Sunamoto told us.

Unlike during the war, we can freely speak our opinions and take actions based on our own will. I appreciate that I was born in such an age, and I am looking for something I can become absorbed in. (Nanase Shode, 14)

Recognize again the importance of peace

This was my first time listening to an account of the atomic bombing. I was surprised at Mr. Sunamoto’s action. Although he was injured himself, he helped his classmates. When I saw his scar, I strongly felt the terror of the atomic bomb.

Mr. Sunamono said, “Peace makes it possible for us to take for granted that we can do whatever we want.” Those words made me think I should always remember the importance of ordinary daily life. (Moe Nakano, 15)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

After graduating from Hiroshima Technical School (now, Faculty of Engineering, Hiroshima University), Mr. Sunamoto started working at what was then a Nissan Diesel retailer. He was transferred to various branches, including Okayama and Tokuyama. Despite fighting his atomic bomb disease, he became president of the retail company in Yamaguchi.

He looked very lively while talking about automobiles and his job. He told us that when he went to technical school, he studied wood-powered cars, which use firewood as fuel. He exchanged about 96,000 business cards in his career.

On entering the company, he stayed in Saitama Prefecture for training. During breaks, he talked about his A-bomb experience. Sitting in a circle, his co-workers listened to his story; he was quite popular at recess. He was surprised that people around him were so interested in his experience. He felt no prejudice from them against atomic bomb survivors.

During the trainee period, he contracted a high fever, which seemed to be caused by the atomic bombing. He had to take a temporary leave from work. Later, he experienced other atomic bomb diseases, including cancer and heart trouble. Nevertheless, he refused to succumb to difficulties, maintaining a passion for his job. I think I learned from him the importance of never giving up. (Sakiko Masuda)

(Originally published on June 11, 2013)

After the bomb, his body was weak, but he swallowed his tears and devoted himself to work

Suddenly, a strong flash hit him from in front and to the left. He lost consciousness. When he came to, he noticed he was in the ruins of the factory next door. He had been blown there by the blast. Working desperately, he dug himself out of the debris, then pulled out three friends. One friend said, “You’re really hurt.” That was when he found he was covered with blood.

Yoshika Sunamoto, 82, was at 14 at the time of the atomic bombing. He was a third-year student at First Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High School (now Kokutaiji High School, located in Naka Ward). On August 6, 1945, he was mobilized to work in a military factory in Funairi Kawaguchi-cho (now in Naka Ward), about 2km from the hypocenter. He was working without a shirt.

The flash burned the left side of his body. His left arm suffered a gash 8cm long; he still carries the scar.

He went with some friends to Hiroshima First Municipal Girl’s School (now, Funairi High School), which served as the local evacuation center. Later, he sought treatment at an army hospital in Eba (now, Naka Ward).

However, the army hospital was full of seriously injured patients. He gave up on treatment, deciding to return to his home in Midori-machi (now, Minami Ward). His way was frequently blocked by fallen houses and fire, but getting a ride across one river in a boat and walking across another at low tide, he finally made it home.

A military doctor who was his father’s friend examined his injuries and said they would take six months to heal. That prognosis shocked him so badly he cried all night. He was afraid he would not be well in time to take the entrance examination for the Naval Academy and its Navy officer training.

The war ended, and after treatment and recuperation for a half-year, he returned to junior high school. Then, he entered Hiroshima Technical School (now the Faculty of Engineering at Hiroshima University). Anticipating progress in motorization, he joined the Auto Engineering Department. After graduation, he found a job as an engineer at an automobile retailer.

However, that summer, while training for his new job at an automobile factory in Saitama Prefecture, he was attacked by a high fever of unknown origin. A persistent temperature higher than 39 degrees forced him to return to Hiroshima.

He was unable to work for a year. “Why do I have such a weak body?” Blaming himself for not living up to his own expectations, he cried again and again in frustration.

When he did return to work, he had to battle prostate cancer and hypertensive heart disease, both certified as atomic bomb diseases. He served as president of an automobile retail company in Yamaguchi City, working there as advisor until 1998, he retired at age 67. Today he lives with his wife in Fuchu Town, Hiroshima.

His advice to youth: “Even if you fail, don’t give up. Keep working to accomplish what you set out to do.” (Sakiko Masuda, Staff Writer)

Hiroshima Insight

A-bomb disease Certification: The discrepancy between the judiciary and the bureaucracy

One remedy provided by the Atomic Bomb Victims’ Relief Law is a system to certify “atomic bomb diseases”. The government provides a special medical allowance (approximately 136,000 yen per month) to certified atomic bomb survivors whose diseases (cancer, leukemia, etc.) or injuries were caused by the atomic bombing and require ongoing treatment. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare certifies these atomic bomb diseases.

However, for many years the vast majority of applications were rejected. In fact, less than 1% of atomic bomb survivors were certified.

In 2003, a group of atomic bomb survivors whose applications were rejected brought a class action suit against the government in several district courts around Japan, including Hiroshima, demanding certification.

The government lost these cases one after another, so the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare revised its criteria for certification in April 2008. Since that time, the number of certifications has increased greatly.

However, a significant gap remains between the judiciary and the government agencies involved. For example, even when a court admits an atomic bomb disease, applications for certification are often rejected. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare established an expert review committee in December 2010, and the review is still underway.

Criteria for certification of atomic bomb disease

* Based on Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare documents

① Experienced atomic bombing within 3.5km of the hypocenter

② Entered within 2km of the hypocenter within 100 hours of the atomic bombing

③ Stayed for at least one week within 2km of the hypocenter within two weeks of the atomic bombing

Persons shall be certified who meet one of the three conditions above and develop one of seven diseases, including solid cancers (e.g., gastric, colorectal, breast and esophageal cancer), leukemia, hyperthyroidism and radiation cataract.

In other cases, decisions shall be made after examining a comprehensive set of factors, including level of radiation exposure.

Teenagers’ Impressions

I want to set a goal and go for it

“Go for it. Set your goal and accomplish what you set out to do,” Mr. Sunamoto told us.

Unlike during the war, we can freely speak our opinions and take actions based on our own will. I appreciate that I was born in such an age, and I am looking for something I can become absorbed in. (Nanase Shode, 14)

Recognize again the importance of peace

This was my first time listening to an account of the atomic bombing. I was surprised at Mr. Sunamoto’s action. Although he was injured himself, he helped his classmates. When I saw his scar, I strongly felt the terror of the atomic bomb.

Mr. Sunamono said, “Peace makes it possible for us to take for granted that we can do whatever we want.” Those words made me think I should always remember the importance of ordinary daily life. (Moe Nakano, 15)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

After graduating from Hiroshima Technical School (now, Faculty of Engineering, Hiroshima University), Mr. Sunamoto started working at what was then a Nissan Diesel retailer. He was transferred to various branches, including Okayama and Tokuyama. Despite fighting his atomic bomb disease, he became president of the retail company in Yamaguchi.

He looked very lively while talking about automobiles and his job. He told us that when he went to technical school, he studied wood-powered cars, which use firewood as fuel. He exchanged about 96,000 business cards in his career.

On entering the company, he stayed in Saitama Prefecture for training. During breaks, he talked about his A-bomb experience. Sitting in a circle, his co-workers listened to his story; he was quite popular at recess. He was surprised that people around him were so interested in his experience. He felt no prejudice from them against atomic bomb survivors.

During the trainee period, he contracted a high fever, which seemed to be caused by the atomic bombing. He had to take a temporary leave from work. Later, he experienced other atomic bomb diseases, including cancer and heart trouble. Nevertheless, he refused to succumb to difficulties, maintaining a passion for his job. I think I learned from him the importance of never giving up. (Sakiko Masuda)

(Originally published on June 11, 2013)