Kingo Kawahara, 87, Mukaiharacho, Akitakata City

Sep. 4, 2013

Ran freight train carrying wounded out of the A-bombed city

Overcame ill health and discrimination to work as teacher

At the time of the atomic bombing, Kingo Kawahara was a train conductor for Japan’s National Railway. In the aftermath of the blast, he helped carry the wounded on a freight train running on the Geibi Line, bound for Bingotokaichi Station (present-day Miyoshi Station in Miyoshi City). Although he suffered burns to the back of his head and his back, he kept up the spirits of the injured while running the train with the locomotive driver.

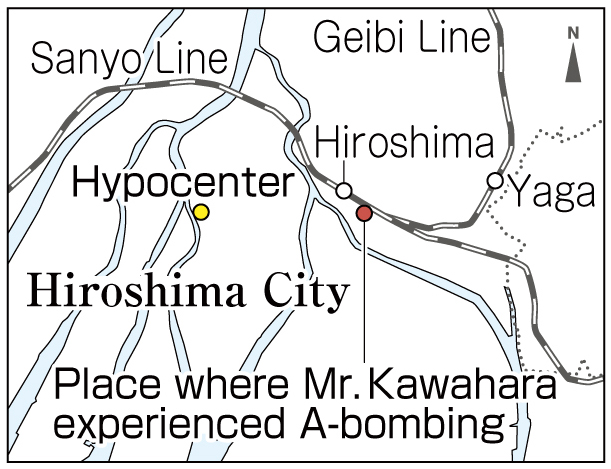

On August 6, 1945, Mr. Kawahara, who was 19 then, was walking to the switchyard, located on the east side of Hiroshima Station (in today’s Minami Ward) to take his shift as a crew member. Suddenly, from behind, there was a huge white flash and he was blown into the air. After a while, when he raised his head, he found that he was surrounded by darkness and dust. He was about 2.1 kilometers from the hypocenter.

Still, he hurried to the switchyard. After finding other crew members who had survived the blast, including a locomotive driver, the pair decided to use the freight train. Mr. Kawahara then went on foot to the next station on the Geibi Line, Yaga Station (in today’s Higashi Ward), to check if the railroad tracks were clear.

When the train arrived at Yaga Station, he went to Yaga National School (now Yaga Elementary School in Higashi Ward), near the station, to seek treatment for his burns. But he saw that many of the victims had suffered more serious burns, with even their skin peeling off. “I can’t ask for ointment for my minor burns,” he thought, and decided to leave without treatment.

Mr. Kawahara and the driver of the freight train stopped five or six times along their route north, picking up the injured alongside the tracks. He doesn’t remember the exact number of passengers they carried, but believes it was around 100. At each station, many people crowded around the train, anxiously seeking information about the safety of family members and friends.

Mr. Kawahara reached Bingotokaichi, then returned to his house in Mukaihara, part of today’s Akitakata City. He suffered from hair loss, one of the acute symptoms of radiation exposure. The scars from his burns lingered for more than 10 years.

He was also the victim of discrimination. At a meeting for an arranged marriage, he was rebuffed with the words, “Radiation is contagious.” He often wished he could flee from his life as an A-bomb survivor and tried not to think about the bombing.

After the war, he quit his job as a conductor and became an elementary school teacher, a longtime dream. He retired in 1987, as the principal of Odahigashi Elementary School in Koda Town, part of today’s Akitakata City. After that, he served as a member of the Mukaihara town assembly, and as the principal of a kindergarten in Asakita Ward until March of this year.

Today, he lives with his wife and they have seven grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. “I don’t want children to suffer the experiences I did,” he said. “I want them to understand how pointless the war was, and convey that message to the generations to come.” (Sakiko Masuda, Staff Writer)

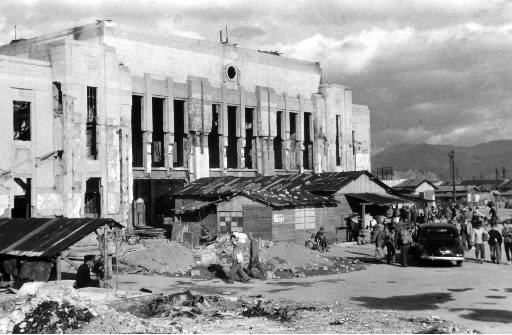

Hiroshima Station: Concrete station building was gutted by fire

Hiroshima Station is located in Minami Ward, about 2 kilometers from the hypocenter, and was severely damaged in the atomic bombing. It was Japan’s first concrete station building, but the ceiling collapsed and the building was gutted by fire. With the number of visitors to the station increasing, an additional waiting room had been built, but that wooden structure burned down, too. Seventy-eight bodies were reportedly found at the site.

The day after the blast, service on the Ujina Line (now discontinued), which was being used as a railway for the military, was restored. Operations on other lines were gradually resumed, too. Trains played an important role in relief efforts after the bombing by carrying the wounded to safer locations.

In fact, in the aftermath of the blast, trains shuttled back and forth between the city and stations located in areas that had escaped damage. For instance, a record made on August 6 by a worker of the National Railway indicates that, on the Geibi Line, apart from the freight train which carried the injured from Hiroshima to Bingotokaichi Station (present-day Miyoshi Station in the city of Miyoshi), a relief train departed from Bingotokaichi Station and went to Yaga Station (in today’s Higashi Ward), one stop before Hiroshima Station, then returned carrying survivors of the bombing.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Think about other people’s feelings

At the school being used as a relief station, where Mr. Kawahara went for treatment, he saw some badly wounded people and he thought, “My burns aren’t as serious as theirs, so I shouldn’t ask for anything.” Like Mr. Kawahara, acting with compassion for others would help bring peace. If we try to have compassion and think about other people’s feelings in our daily lives, we would be able to build a world free from bullying and war. (Shino Taniguchi, 14)

Hold the tragedy of the atomic bombing in mind

“War deprives people of conscience,” Mr. Kawahara told us. After the atomic bombing, when he saw a lot of bodies being cremated or floating on the river, he said that he didn’t feel anything at all. War makes death ordinary, and it shouldn’t be fought. I will never forget Mr. Kawahara’s wish that war and the atomic bombing must never be repeated. (Saaya Teranishi, 17)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

Mr. Kawahara was absent from his job as a train conductor only on August 7, the day after the atomic bombing, and returned to work on August 8. In the days that followed, when he had time off from work, he would walk through the city of Hiroshima in search of missing family members and friends. The city, he recalled, looked like hell itself.

He saw such sights as bodies floating on the river, a person who had died after thrusting his head into a water cistern used for fire fighting, and people pleading for water. He heard calls for help from beneath the wreckage of buildings, but could do nothing but put his hands together in prayer and cry.

He carried many wounded passengers on his train. He still recalls a man with severe burns who died before they arrived at the man’s destination. Mr. Kawahara tried to encourage the man by saying, “Hold on, the train will reach the station soon,” but he passed away soon after.

When he thinks back on those days, he feels great pain, as well as gratitude that he survived. (Sakiko Masuda)

(Originally published on August 26, 2013)

Overcame ill health and discrimination to work as teacher

At the time of the atomic bombing, Kingo Kawahara was a train conductor for Japan’s National Railway. In the aftermath of the blast, he helped carry the wounded on a freight train running on the Geibi Line, bound for Bingotokaichi Station (present-day Miyoshi Station in Miyoshi City). Although he suffered burns to the back of his head and his back, he kept up the spirits of the injured while running the train with the locomotive driver.

On August 6, 1945, Mr. Kawahara, who was 19 then, was walking to the switchyard, located on the east side of Hiroshima Station (in today’s Minami Ward) to take his shift as a crew member. Suddenly, from behind, there was a huge white flash and he was blown into the air. After a while, when he raised his head, he found that he was surrounded by darkness and dust. He was about 2.1 kilometers from the hypocenter.

Still, he hurried to the switchyard. After finding other crew members who had survived the blast, including a locomotive driver, the pair decided to use the freight train. Mr. Kawahara then went on foot to the next station on the Geibi Line, Yaga Station (in today’s Higashi Ward), to check if the railroad tracks were clear.

When the train arrived at Yaga Station, he went to Yaga National School (now Yaga Elementary School in Higashi Ward), near the station, to seek treatment for his burns. But he saw that many of the victims had suffered more serious burns, with even their skin peeling off. “I can’t ask for ointment for my minor burns,” he thought, and decided to leave without treatment.

Mr. Kawahara and the driver of the freight train stopped five or six times along their route north, picking up the injured alongside the tracks. He doesn’t remember the exact number of passengers they carried, but believes it was around 100. At each station, many people crowded around the train, anxiously seeking information about the safety of family members and friends.

Mr. Kawahara reached Bingotokaichi, then returned to his house in Mukaihara, part of today’s Akitakata City. He suffered from hair loss, one of the acute symptoms of radiation exposure. The scars from his burns lingered for more than 10 years.

He was also the victim of discrimination. At a meeting for an arranged marriage, he was rebuffed with the words, “Radiation is contagious.” He often wished he could flee from his life as an A-bomb survivor and tried not to think about the bombing.

After the war, he quit his job as a conductor and became an elementary school teacher, a longtime dream. He retired in 1987, as the principal of Odahigashi Elementary School in Koda Town, part of today’s Akitakata City. After that, he served as a member of the Mukaihara town assembly, and as the principal of a kindergarten in Asakita Ward until March of this year.

Today, he lives with his wife and they have seven grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. “I don’t want children to suffer the experiences I did,” he said. “I want them to understand how pointless the war was, and convey that message to the generations to come.” (Sakiko Masuda, Staff Writer)

Hiroshima Insight

Hiroshima Station: Concrete station building was gutted by fire

Hiroshima Station is located in Minami Ward, about 2 kilometers from the hypocenter, and was severely damaged in the atomic bombing. It was Japan’s first concrete station building, but the ceiling collapsed and the building was gutted by fire. With the number of visitors to the station increasing, an additional waiting room had been built, but that wooden structure burned down, too. Seventy-eight bodies were reportedly found at the site.

The day after the blast, service on the Ujina Line (now discontinued), which was being used as a railway for the military, was restored. Operations on other lines were gradually resumed, too. Trains played an important role in relief efforts after the bombing by carrying the wounded to safer locations.

In fact, in the aftermath of the blast, trains shuttled back and forth between the city and stations located in areas that had escaped damage. For instance, a record made on August 6 by a worker of the National Railway indicates that, on the Geibi Line, apart from the freight train which carried the injured from Hiroshima to Bingotokaichi Station (present-day Miyoshi Station in the city of Miyoshi), a relief train departed from Bingotokaichi Station and went to Yaga Station (in today’s Higashi Ward), one stop before Hiroshima Station, then returned carrying survivors of the bombing.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Think about other people’s feelings

At the school being used as a relief station, where Mr. Kawahara went for treatment, he saw some badly wounded people and he thought, “My burns aren’t as serious as theirs, so I shouldn’t ask for anything.” Like Mr. Kawahara, acting with compassion for others would help bring peace. If we try to have compassion and think about other people’s feelings in our daily lives, we would be able to build a world free from bullying and war. (Shino Taniguchi, 14)

Hold the tragedy of the atomic bombing in mind

“War deprives people of conscience,” Mr. Kawahara told us. After the atomic bombing, when he saw a lot of bodies being cremated or floating on the river, he said that he didn’t feel anything at all. War makes death ordinary, and it shouldn’t be fought. I will never forget Mr. Kawahara’s wish that war and the atomic bombing must never be repeated. (Saaya Teranishi, 17)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

Mr. Kawahara was absent from his job as a train conductor only on August 7, the day after the atomic bombing, and returned to work on August 8. In the days that followed, when he had time off from work, he would walk through the city of Hiroshima in search of missing family members and friends. The city, he recalled, looked like hell itself.

He saw such sights as bodies floating on the river, a person who had died after thrusting his head into a water cistern used for fire fighting, and people pleading for water. He heard calls for help from beneath the wreckage of buildings, but could do nothing but put his hands together in prayer and cry.

He carried many wounded passengers on his train. He still recalls a man with severe burns who died before they arrived at the man’s destination. Mr. Kawahara tried to encourage the man by saying, “Hold on, the train will reach the station soon,” but he passed away soon after.

When he thinks back on those days, he feels great pain, as well as gratitude that he survived. (Sakiko Masuda)

(Originally published on August 26, 2013)