Kaneko Harada, 86, Asakita Ward, Hiroshima

Nov. 7, 2013

Unable to help her coworker: Fell unconscious, into “the bottom of a pitch-black sea”

Kaneko Harada (nee Sakota), 86, experienced the atomic bombing in Higashi Ebisucho (part of present-day Naka Ward, about 1 kilometer from the hypocenter). As she was fleeing the area, and passed by the Enkobashi Bridge (in today’s Minami Ward), in front of Hiroshima Station, someone called her name. The person’s face was burned black, with gleaming eyes. Ms. Harada recognized her as a woman she worked with and took her hand, set to escape together. But the skin on the woman’s hand peeled right off. “It couldn’t be helped,” she said, the memory of that scene still haunting her.

At the time of the atomic bombing, Ms. Harada was 18 years old and working in a clothing factory in Higashi Ebisucho, making military clothes. The morning of August 6 was hot, and because the air raid warning had been lifted, she removed her monpe (traditional Japanese work pants) and was about to start working at her sewing machine. But then there was a flash, the ceiling and its glass window collapsed, and everything went dark. She remembers smelling a foul, earthy odor from the walls.

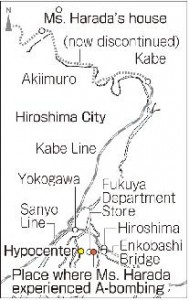

She doesn’t know how much time passed after that. When it became lighter, she was able to slip out from the back of the building, where the air raid shelter was located. Her body, though, was now bloodied by broken glass. Piles of rubble stood everywhere, and she wasn’t sure where the roads were, but she tried heading toward Fukuya Department Store (in today’s Naka Ward). When she found the store on fire, she ran in the opposite direction, toward Hiroshima Station.

It was then that she met her coworker at Enkobashi Bridge. However, because the woman was heading to Yokogawa to find her mother, they parted there. Later, Ms. Harada heard that she passed away in Kaita (now, the town of Kaita in Hiroshima Prefecture).

To get home to Imuro (in today’s Asakita Ward), Ms. Harada walked on in her bare feet. From around Fukuda (in Higashi Ward), she was given a ride on a truck and reached Kabe Station (in Asakita Ward). From there, she rode a freight train on the Kabe Line (which was later discontinued), finally arriving home shortly after 9 o’clock that night.

Through August, she cooked for her family while drinking a home remedy of “dokudami” tea each day. Gradually, however, purple spots appeared on her body and whenever she brushed her hair, clumps would come out. On September 1, she finally felt so weak that she was unable to move. She was carried to a hospital in a two-wheeled cart, and given injections in her arms and legs. After returning home, she suffered a high fever of 42 degrees Celsius and fell unconscious.

For about a month she slipped in and out of consciousness, her eyes opening at times during the night. Over and over, she felt as if she was “falling to the bottom of a pitch-black sea.” Looking back at that time, she said, “It was hell.” One day, she coughed up a large amount of something that seemed like black blood. Ms. Harada believes this enabled her to expel the poison from her system. One and a half years later, she was finally able to return to work.

“It was such a hard time. We have to make sure there’s never another war.” This is Ms. Harada’s strong hope. (Rie Nii, Staff Writer)

Enkobashi Bridge: Bridge ornaments used as scrap metal during the war

Enkobashi Bridge, which spans Enkogawa River, is located in Minami Ward, on the southeast side of Ekimae-Ohashi Bridge in front of Hiroshima Station. It was completed in 1926.

At that time, there were ornaments on the newel posts at the ends of the bridge railings: bronze figures of eagles with their wings spread and lamps were perched on globes.

The railings were also adorned with the metal ornaments of two monkeys grasping a peach. The beautiful ornaments led to the bridge being called “Hiroshima’s finest bridge.”

During the war, however, because of a shortage of metal, an order to collect available metal was issued in 1941. In line with this order, the bronze figures of eagles and the monkeys with their peach had to be given to the government as scrap. New ornaments on the newel posts and bridge rails were then crafted from stone.

Though the bridge was located about 1.8 kilometers from the hypocenter, the atomic bomb destroyed only a portion of the railing. As a result, many of the wounded traveled over this bridge to flee the hypocenter area.

Today, Enkobashi Bridge is the oldest among all 2,900 bridges under the city’s management. In the future, the old metal ornament on the newel post on the south end of the bridge will be restored as a memorial to the past.

It has been nearly 90 years since Enkobashi Bridge was constructed in Minami Ward. In the aftermath of the atomic bombing, many people crossed over this bridge to flee the area.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Abolish nuclear weapons

Ms. Harada described the city, just after the atomic bombing, as “completely black and the roads were ruined.” At first, I didn’t understand what she meant. But the more I heard her speak, the more I was able to imagine what it was like in Hiroshima back then, like a burnt plain, with everything destroyed. She told us, “War is hell. There shouldn’t be any more wars.” I want to help end war and abolish nuclear weapons. (Moe Nakano, 14)

Seeing the horror of death

When Ms. Harada fell unconscious, and was hovering between life and death, she felt like she was “falling to the bottom of a pitch-black sea.” Until that moment, I hadn’t pondered death very deeply, and her words made me think about the horror of dying.

I think war and atomic bombs, which have caused such horror for so many people, must be abolished. (Ishin Nakahara, 15)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

When Ms. Harada fell unconscious, neighbors gathered and kept vigil over her. When she awoke at night, the people around her were very surprised.

Her mother and her brother’s wife took Ms. Harada, who was then semiconscious, to a hospital, traveling over bumpy roads on a two-wheel cart. And on days the family didn’t have enough to eat, her mother would venture into the mountains to ask a farmer for some apples to give to her.

Ms. Harada’s coworkers at the time of the atomic bombing passed away, one after another. Although Ms. Harada herself suffered from the acute symptoms of radiation sickness, she managed to survive. “That would have been my fate, too,” she said. “I hope to live to the age of 90.” (Rie Nii)

(Originally published on October 14, 2013)

Kaneko Harada (nee Sakota), 86, experienced the atomic bombing in Higashi Ebisucho (part of present-day Naka Ward, about 1 kilometer from the hypocenter). As she was fleeing the area, and passed by the Enkobashi Bridge (in today’s Minami Ward), in front of Hiroshima Station, someone called her name. The person’s face was burned black, with gleaming eyes. Ms. Harada recognized her as a woman she worked with and took her hand, set to escape together. But the skin on the woman’s hand peeled right off. “It couldn’t be helped,” she said, the memory of that scene still haunting her.

At the time of the atomic bombing, Ms. Harada was 18 years old and working in a clothing factory in Higashi Ebisucho, making military clothes. The morning of August 6 was hot, and because the air raid warning had been lifted, she removed her monpe (traditional Japanese work pants) and was about to start working at her sewing machine. But then there was a flash, the ceiling and its glass window collapsed, and everything went dark. She remembers smelling a foul, earthy odor from the walls.

She doesn’t know how much time passed after that. When it became lighter, she was able to slip out from the back of the building, where the air raid shelter was located. Her body, though, was now bloodied by broken glass. Piles of rubble stood everywhere, and she wasn’t sure where the roads were, but she tried heading toward Fukuya Department Store (in today’s Naka Ward). When she found the store on fire, she ran in the opposite direction, toward Hiroshima Station.

It was then that she met her coworker at Enkobashi Bridge. However, because the woman was heading to Yokogawa to find her mother, they parted there. Later, Ms. Harada heard that she passed away in Kaita (now, the town of Kaita in Hiroshima Prefecture).

To get home to Imuro (in today’s Asakita Ward), Ms. Harada walked on in her bare feet. From around Fukuda (in Higashi Ward), she was given a ride on a truck and reached Kabe Station (in Asakita Ward). From there, she rode a freight train on the Kabe Line (which was later discontinued), finally arriving home shortly after 9 o’clock that night.

Through August, she cooked for her family while drinking a home remedy of “dokudami” tea each day. Gradually, however, purple spots appeared on her body and whenever she brushed her hair, clumps would come out. On September 1, she finally felt so weak that she was unable to move. She was carried to a hospital in a two-wheeled cart, and given injections in her arms and legs. After returning home, she suffered a high fever of 42 degrees Celsius and fell unconscious.

For about a month she slipped in and out of consciousness, her eyes opening at times during the night. Over and over, she felt as if she was “falling to the bottom of a pitch-black sea.” Looking back at that time, she said, “It was hell.” One day, she coughed up a large amount of something that seemed like black blood. Ms. Harada believes this enabled her to expel the poison from her system. One and a half years later, she was finally able to return to work.

“It was such a hard time. We have to make sure there’s never another war.” This is Ms. Harada’s strong hope. (Rie Nii, Staff Writer)

Hiroshima Insight

Enkobashi Bridge: Bridge ornaments used as scrap metal during the war

Enkobashi Bridge, which spans Enkogawa River, is located in Minami Ward, on the southeast side of Ekimae-Ohashi Bridge in front of Hiroshima Station. It was completed in 1926.

At that time, there were ornaments on the newel posts at the ends of the bridge railings: bronze figures of eagles with their wings spread and lamps were perched on globes.

The railings were also adorned with the metal ornaments of two monkeys grasping a peach. The beautiful ornaments led to the bridge being called “Hiroshima’s finest bridge.”

During the war, however, because of a shortage of metal, an order to collect available metal was issued in 1941. In line with this order, the bronze figures of eagles and the monkeys with their peach had to be given to the government as scrap. New ornaments on the newel posts and bridge rails were then crafted from stone.

Though the bridge was located about 1.8 kilometers from the hypocenter, the atomic bomb destroyed only a portion of the railing. As a result, many of the wounded traveled over this bridge to flee the hypocenter area.

Today, Enkobashi Bridge is the oldest among all 2,900 bridges under the city’s management. In the future, the old metal ornament on the newel post on the south end of the bridge will be restored as a memorial to the past.

It has been nearly 90 years since Enkobashi Bridge was constructed in Minami Ward. In the aftermath of the atomic bombing, many people crossed over this bridge to flee the area.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Abolish nuclear weapons

Ms. Harada described the city, just after the atomic bombing, as “completely black and the roads were ruined.” At first, I didn’t understand what she meant. But the more I heard her speak, the more I was able to imagine what it was like in Hiroshima back then, like a burnt plain, with everything destroyed. She told us, “War is hell. There shouldn’t be any more wars.” I want to help end war and abolish nuclear weapons. (Moe Nakano, 14)

Seeing the horror of death

When Ms. Harada fell unconscious, and was hovering between life and death, she felt like she was “falling to the bottom of a pitch-black sea.” Until that moment, I hadn’t pondered death very deeply, and her words made me think about the horror of dying.

I think war and atomic bombs, which have caused such horror for so many people, must be abolished. (Ishin Nakahara, 15)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

When Ms. Harada fell unconscious, neighbors gathered and kept vigil over her. When she awoke at night, the people around her were very surprised.

Her mother and her brother’s wife took Ms. Harada, who was then semiconscious, to a hospital, traveling over bumpy roads on a two-wheel cart. And on days the family didn’t have enough to eat, her mother would venture into the mountains to ask a farmer for some apples to give to her.

Ms. Harada’s coworkers at the time of the atomic bombing passed away, one after another. Although Ms. Harada herself suffered from the acute symptoms of radiation sickness, she managed to survive. “That would have been my fate, too,” she said. “I hope to live to the age of 90.” (Rie Nii)

(Originally published on October 14, 2013)