Harue Mizuta, 88, Asaminami Ward, Hiroshima

Dec. 6, 2013

A-bomb shattered the work she loved

War prevented hopes and desires

When Harue Mizuta, now 88, was in first grade, she admired a female teacher so much that this motivated her to pursue the dream of becoming a teacher herself. But at the age of 20, four years after she began teaching at Kanzaki National School (now, Kanzaki Elementary School in Naka Ward, Hiroshima), her career as a teacher was shattered.

It was summer, the morning of August 6, 1945. Ms. Mizuta was at the school after spending the night there on watch. After eating breakfast, she was washing the dishes of the other teachers and the principal who had been on duty the night before, too. The morning meeting was scheduled for 8:15 in the teachers’ room so she was in a hurry. Then suddenly the ceiling collapsed, shards of glass were flying through the air, and she fell unconscious.

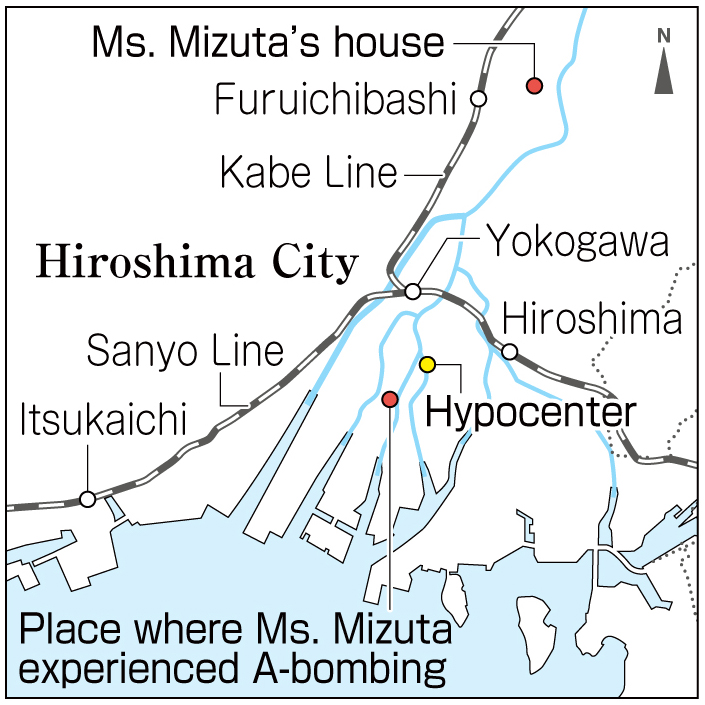

She was pulled from the wreckage of the building by the principal or perhaps a civil defense volunteer at the school, then moved to an air raid shelter. But the principal told her to head to an evacuation site. Along the way, she came across a student who had graduated from Kanzaki National School and was now attending Hiroshima Jissen High School (today’s Suzugamine Junior High and High School), located in Inokuchi Village (part of present-day Nishi Ward). Ms. Mizuta took the girl’s hand and they walked on toward Itsukaichi (now part of Saeki Ward), which was a designated evacuation site.

Before long, black rain fell from the sky. The thick, sticky liquid clung to her face, bloodied by glass fragments and roof tiles, and her white blouse and monpe (traditional Japanese work pants). But they continued walking.

When they finally arrived in Itsukaichi, Ms. Mizuta fainted. How much time passed, Ms. Mizuta doesn’t know, but a woman from a nearby house told her that the whole transportation system had been destroyed. So she spent the next two days crossing a mountain pass, on foot, to her home in Higashino (part of present-day Asaminami Ward).

Her mother, Akio, went searching for her at Kanzaki National School. When she found Ms. Mizuta’s name on a list of the missing, affixed to the school’s rear gate, she thought her daughter had died in the blast. Her mother was overjoyed, then, when Ms. Mizuta appeared at home. “You made it back!” her mother said, patting her shoulders and legs. “You need to rest now.”

A neighbor applied Mercurochrome to the cuts on her face. Later, however, she suffered hair loss and bloody stools. “I thought I was dying,” she recalled.

She often moved to cooler parts of the house to rest, her mother tending to her. A short while later, she married her husband, Hisato, who was demobilized from the military. “I didn’t do any work to help repay my parents,” she said with regret.

“Today you can study and go to college,” she said. “You can take peace studies. You can have hope and do anything that you want to do. But we weren’t able to do any of these things.” She hopes, therefore, that peace will be preserved. (Rie Nii, Staff Writer)

Kanzaki National School: Destroyed by the blast and razed by fire

Kanzaki National School (now, Kanzaki Elementary School), located about 1.2 kilometers southwest of the hypocenter, lost 140 students, as well as eight teachers and staff, to the atomic bombing.

At the time of the bombing, 1,860 students were enrolled in the school. Of these, 1,440 had earlier been evacuated to the countryside. The other 420 students remained at home and continued attending the school or studied at local temples.

The wooden, two-story school building was destroyed in the blast and engulfed in fire. About 25 students had already arrived at school, but apparently died when the building collapsed. The late Keiji Nakazawa, a manga artist widely known for Barefoot Gen, which depicted the bombing, was a first grader at the school. The blast occurred just before he entered the school grounds through the gate on the school’s west side. A concrete wall shielded him from the blast, saving his life.

The children who were evacuated to the countryside were safely out of harm’s way. But some of these children became orphans after family members and relatives were killed.

Because the school building was destroyed, after the war classes resumed at Honkawa National School and Funairi National School. In April 1950, Kanzaki Elementary School was reborn. That September, a new school building was completed at its present location, about 100 meters northeast of where the old building had stood before the war.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Learn languages and communicate with others

“Though talking things out is better, words aren’t used in war,” Ms. Mizuta told us. During war, she said, the intention is to hurt one another.

These days, we can talk together, as individuals, with people from other countries. To maintain peace, we should learn other languages and communicate with the people of the world. (Shino Taniguchi, 15)

Imagining the terrible state of the city

In the aftermath of the atomic bombing, no one realized that the black rain would be harmful to people. Ms. Mizuta was exposed to the black rain while fleeing through a burnt field. As I listened to her story, I could clearly imagine the terrible state of the city, and it frightened me. We have to convey the horror of war and the importance of peace to the world and to the future. (Kyohei Kajimoto, 17)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

Ms. Mizuta was a third grade teacher at the time of the atomic bombing. Prior to the attack, her students were evacuated en masse to a temple in the northern part of Hiroshima Prefecture, and went to a local school there. Ms. Mizuta was able to visit them before the bombing. The children there were lonely, spending their days apart from their parents. When she said goodbye to the children, who were heading off to school in the morning, both Ms. Mizuta and her students couldn’t help shedding tears.

After the war, Ms. Mizuta met one of her former students for the first time in a long while. The student told her, “I don’t have the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate.” Because the student’s family had suffered the bombing, and no one was able to pick her up, she had to remain at the evacuation site and couldn’t return to the city of Hiroshima by August 20. That day became the criteria for applicants to successfully obtain the certificate. “I should have gone to pick her up,” Ms. Mizuta said. “I was at home, being lazy.” In reality, though, she was suffering from the acute symptoms of radiation exposure at the time. “But what’s done is done. It can’t be helped,” she said, sounding as if she was trying to convince herself. Apparently, she has felt remorse continuously over the past 68 years and no remedy seems to exist for easing her heartache. (Rie Nii)

(Originally published on November 25, 2013)

War prevented hopes and desires

When Harue Mizuta, now 88, was in first grade, she admired a female teacher so much that this motivated her to pursue the dream of becoming a teacher herself. But at the age of 20, four years after she began teaching at Kanzaki National School (now, Kanzaki Elementary School in Naka Ward, Hiroshima), her career as a teacher was shattered.

It was summer, the morning of August 6, 1945. Ms. Mizuta was at the school after spending the night there on watch. After eating breakfast, she was washing the dishes of the other teachers and the principal who had been on duty the night before, too. The morning meeting was scheduled for 8:15 in the teachers’ room so she was in a hurry. Then suddenly the ceiling collapsed, shards of glass were flying through the air, and she fell unconscious.

She was pulled from the wreckage of the building by the principal or perhaps a civil defense volunteer at the school, then moved to an air raid shelter. But the principal told her to head to an evacuation site. Along the way, she came across a student who had graduated from Kanzaki National School and was now attending Hiroshima Jissen High School (today’s Suzugamine Junior High and High School), located in Inokuchi Village (part of present-day Nishi Ward). Ms. Mizuta took the girl’s hand and they walked on toward Itsukaichi (now part of Saeki Ward), which was a designated evacuation site.

Before long, black rain fell from the sky. The thick, sticky liquid clung to her face, bloodied by glass fragments and roof tiles, and her white blouse and monpe (traditional Japanese work pants). But they continued walking.

When they finally arrived in Itsukaichi, Ms. Mizuta fainted. How much time passed, Ms. Mizuta doesn’t know, but a woman from a nearby house told her that the whole transportation system had been destroyed. So she spent the next two days crossing a mountain pass, on foot, to her home in Higashino (part of present-day Asaminami Ward).

Her mother, Akio, went searching for her at Kanzaki National School. When she found Ms. Mizuta’s name on a list of the missing, affixed to the school’s rear gate, she thought her daughter had died in the blast. Her mother was overjoyed, then, when Ms. Mizuta appeared at home. “You made it back!” her mother said, patting her shoulders and legs. “You need to rest now.”

A neighbor applied Mercurochrome to the cuts on her face. Later, however, she suffered hair loss and bloody stools. “I thought I was dying,” she recalled.

She often moved to cooler parts of the house to rest, her mother tending to her. A short while later, she married her husband, Hisato, who was demobilized from the military. “I didn’t do any work to help repay my parents,” she said with regret.

“Today you can study and go to college,” she said. “You can take peace studies. You can have hope and do anything that you want to do. But we weren’t able to do any of these things.” She hopes, therefore, that peace will be preserved. (Rie Nii, Staff Writer)

Hiroshima Insight

Kanzaki National School: Destroyed by the blast and razed by fire

Kanzaki National School (now, Kanzaki Elementary School), located about 1.2 kilometers southwest of the hypocenter, lost 140 students, as well as eight teachers and staff, to the atomic bombing.

At the time of the bombing, 1,860 students were enrolled in the school. Of these, 1,440 had earlier been evacuated to the countryside. The other 420 students remained at home and continued attending the school or studied at local temples.

The wooden, two-story school building was destroyed in the blast and engulfed in fire. About 25 students had already arrived at school, but apparently died when the building collapsed. The late Keiji Nakazawa, a manga artist widely known for Barefoot Gen, which depicted the bombing, was a first grader at the school. The blast occurred just before he entered the school grounds through the gate on the school’s west side. A concrete wall shielded him from the blast, saving his life.

The children who were evacuated to the countryside were safely out of harm’s way. But some of these children became orphans after family members and relatives were killed.

Because the school building was destroyed, after the war classes resumed at Honkawa National School and Funairi National School. In April 1950, Kanzaki Elementary School was reborn. That September, a new school building was completed at its present location, about 100 meters northeast of where the old building had stood before the war.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Learn languages and communicate with others

“Though talking things out is better, words aren’t used in war,” Ms. Mizuta told us. During war, she said, the intention is to hurt one another.

These days, we can talk together, as individuals, with people from other countries. To maintain peace, we should learn other languages and communicate with the people of the world. (Shino Taniguchi, 15)

Imagining the terrible state of the city

In the aftermath of the atomic bombing, no one realized that the black rain would be harmful to people. Ms. Mizuta was exposed to the black rain while fleeing through a burnt field. As I listened to her story, I could clearly imagine the terrible state of the city, and it frightened me. We have to convey the horror of war and the importance of peace to the world and to the future. (Kyohei Kajimoto, 17)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

Ms. Mizuta was a third grade teacher at the time of the atomic bombing. Prior to the attack, her students were evacuated en masse to a temple in the northern part of Hiroshima Prefecture, and went to a local school there. Ms. Mizuta was able to visit them before the bombing. The children there were lonely, spending their days apart from their parents. When she said goodbye to the children, who were heading off to school in the morning, both Ms. Mizuta and her students couldn’t help shedding tears.

After the war, Ms. Mizuta met one of her former students for the first time in a long while. The student told her, “I don’t have the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate.” Because the student’s family had suffered the bombing, and no one was able to pick her up, she had to remain at the evacuation site and couldn’t return to the city of Hiroshima by August 20. That day became the criteria for applicants to successfully obtain the certificate. “I should have gone to pick her up,” Ms. Mizuta said. “I was at home, being lazy.” In reality, though, she was suffering from the acute symptoms of radiation exposure at the time. “But what’s done is done. It can’t be helped,” she said, sounding as if she was trying to convince herself. Apparently, she has felt remorse continuously over the past 68 years and no remedy seems to exist for easing her heartache. (Rie Nii)

(Originally published on November 25, 2013)