Sueko Noboritate, 84, Nishi Ward, Hiroshima

Jan. 23, 2014

Father’s tears, and final words, echo in memory

Suffered painful damage to her knee

Sueko Noboritate (nee Shirakawa), 84, who experienced the atomic bombing at the age of 15 and suffered serious injuries, is unable to forget the tears her father shed before he died. Although he suffered no heavy wounds at the time of the bombing, purple spots later broke out on his body and he passed away 16 days later. His final words were: “Take care of Sueko.”

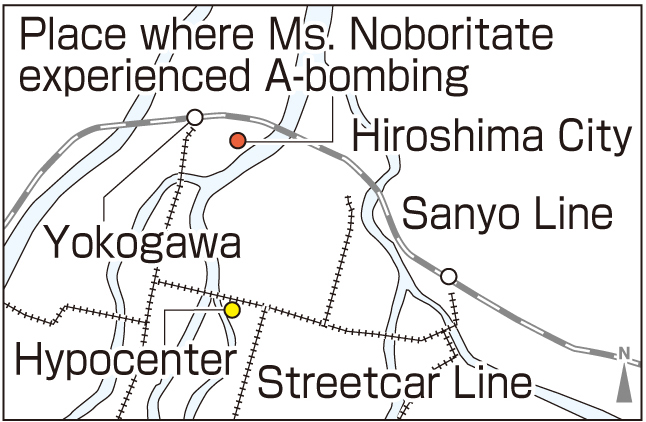

Back then, Ms. Noboritate was a fourth-year student at Hiroshima First Municipal Girl’s School (now, Funairi High School). On the morning of August 6, 1945, she had a day off from the factory where she was mobilized to work for the war effort so she remained at home in Kusunokimachi (part of present-day Nishi Ward), about 1.5 kilometers from the hypocenter.

A neighbor had dropped by and she was at the door with her mother. Suddenly, she saw a flash, “like a spark,” and was blown off her feet by the blast. The next thing she noticed, her face was bleeding.

She tried to move, but wasn’t able to stand. Near her right knee was a gash, 5 centimeters deep, full of splinters of glass. Frantic, she crawled out from the wreckage of their house and looked about. Her mother was pinned under a beam and calling for help. An acquaintance passing by came to her mother’s aid and helped bring them to the nearby Misasa Bridge, where they sought refuge underneath.

There they reunited with Ms. Noboritate’s father, who was working to deliver lumber to the military. He experienced the bombing in the Sakaimachi district (part of present-day Naka Ward), about 700 meters from the hypocenter, but because he was in the shadow of a building, he managed to survive the blast.

That evening, Ms. Noboritate boarded a boat with her parents and fled to a river bank at Oshibacho (part of present-day Nishi Ward). A few days later, her father’s cousin came looking for them, and they traveled by truck to the village of Tusuga (today’s Akiota Town in Hiroshima Prefecture) where her father’s parents lived. Shortly after, her father’s hair began to fall out and his gums started to bleed. While worrying about his daughter, who had suffered serious injuries, he passed away on August 22.

Ms. Noboritate herself suffered from a high fever for some time. By November, she had recovered enough to walk with a cane, and she returned to the city of Hiroshima with her mother, relying on her mother’s relatives for support.

In the spring of 1946, she graduated from high school. On a teacher’s recommendation, she went on to Hiroshima Jogakuin Vocational School (today’s Hiroshima Jogakuin University). At the age of 22, she got married and then had a son. When she was 37, she was asked by people in her community to serve as a volunteer social worker, and she worked to turn around troubled youth for the next 40 years.

Due to the damage suffered to her right knee, for a while she was unable sit in traditional seiza style, with the legs bent behind. She also endured a period when she could not walk in a natural fashion, and she heard some unkind words from others. As she grew older, her knee became so painful that she had trouble sleeping at night. After undergoing surgery in the fall of 2011 to replace the joint with an artificial implant, she can finally walk without pain.

“The wounds left by the atomic bombing have lingered our whole lives,” Ms. Noboritate said, stressing her words. “If a war is about to break out, I would do anything to prevent innocent children from suffering the same misfortunes.” (Sakiko Masuda, Staff Writer)

Hiroshima First Municipal Girl’s School: Words “atomic bomb” not permitted for monument

Hiroshima First Municipal Girl’s School (today’s Funairi High School in Naka Ward) is known as the school which suffered a greater death toll in the atomic bombing than any other school in the city.

On August 6, 1945, all of the 541 first- and second-year students (ages 12 or 13) and seven teachers who were helping to dismantle buildings to create a fire lane in the Kobikicho district (part of present-day Nakajimacho in Naka Ward) perished in the blast. Including the older students and other teachers who died elsewhere in the city, the school lost a total of 676 members of its community.

In 1948 a memorial was erected on the school grounds. The figures of three girls have been engraved on this monument, and the girl in the center is holding a box with the equation “E=mc2”--the formula for the theory of relativity. When the monument was constructed, Japan was still occupied by Allied Forces and so the words “atomic bomb” could not be used at the time. Because people were unable to speak freely about the damage caused by the bombing, the theory of relativity, which led to the creation of the atomic bombs, was engraved on the monument instead.

In 1957, the monument was moved to its present location at the west end of Peace Bridge, in the green belt along Peace Boulevard, near Peace Memorial Park. This was roughly the area where the students from Hiroshima First Municipal Girl’s School were carrying out their work assignment that morning, helping to create a fire lane, and were killed.

Hiroshima First Municipal Girl’s School closed in 1948, then was reborn as Funairi High School.

Teenagers’ Impressions

I won’t discriminate against anyone

Sometimes people said unkind things about Ms. Noboritate, whose leg was badly damaged in the bombing. Each time she thought, “I wish I had my old leg back.” She must have felt such distress, she couldn’t help making this wish. It’s important that we don’t discriminate against other people. I intend to treat everyone the same, and make more friends. (Ishin Nakahara, 15)

Make compromises and forgive one another

“It’s important to make compromises and forgive one another.” These were the words of Ms. Noboritate, who worked for a long time as a volunteer social worker. If everyone behaved with this thought in mind, we could solve most of the conflicts occurring in the world today, and new conflicts wouldn’t break out. In my case, I’ll try not to be too assertive, and I’ll try to maintain good relationships with the people around me. (Yuka Iguchi, 18)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

While attending a vocational school, Ms. Noboritate underwent surgery to repair the damage to her right knee, injured in the atomic bombing. But the operation didn’t go well. Later, she visited an osteopath to massage the leg, and it took a year for her to be able to sit seiza style again. She made her mother’s dream come true, though, when she wore a formal, long-sleeved kimono and could take part in a tea ceremony. Still, the injury didn’t heal completely. As a result of the damage she suffered to her knee, her right leg became two centimeters shorter than her left leg, and she can’t walk for extended periods of time. She was forced to give up her dream of climbing Mt. Fuji.

Because she didn’t want others staring at the prominent scar on her left shoulder, she wouldn’t wear sleeveless blouses and swimsuits. She experienced no discrimination when it came to marriage, but when she had her first child, she made sure that the baby had five digits on each hand and foot. During our interview, she murmured, “What if I hadn’t experienced the atomic bombing, what kind of life would I have had?” Ms. Noboritate lost her father and her good health in the atomic bombing. War, and the atomic bomb, stole these things from an innocent person. (Sakiko Masuda)

(Originally published on January 13, 2014)

Suffered painful damage to her knee

Sueko Noboritate (nee Shirakawa), 84, who experienced the atomic bombing at the age of 15 and suffered serious injuries, is unable to forget the tears her father shed before he died. Although he suffered no heavy wounds at the time of the bombing, purple spots later broke out on his body and he passed away 16 days later. His final words were: “Take care of Sueko.”

Back then, Ms. Noboritate was a fourth-year student at Hiroshima First Municipal Girl’s School (now, Funairi High School). On the morning of August 6, 1945, she had a day off from the factory where she was mobilized to work for the war effort so she remained at home in Kusunokimachi (part of present-day Nishi Ward), about 1.5 kilometers from the hypocenter.

A neighbor had dropped by and she was at the door with her mother. Suddenly, she saw a flash, “like a spark,” and was blown off her feet by the blast. The next thing she noticed, her face was bleeding.

She tried to move, but wasn’t able to stand. Near her right knee was a gash, 5 centimeters deep, full of splinters of glass. Frantic, she crawled out from the wreckage of their house and looked about. Her mother was pinned under a beam and calling for help. An acquaintance passing by came to her mother’s aid and helped bring them to the nearby Misasa Bridge, where they sought refuge underneath.

There they reunited with Ms. Noboritate’s father, who was working to deliver lumber to the military. He experienced the bombing in the Sakaimachi district (part of present-day Naka Ward), about 700 meters from the hypocenter, but because he was in the shadow of a building, he managed to survive the blast.

That evening, Ms. Noboritate boarded a boat with her parents and fled to a river bank at Oshibacho (part of present-day Nishi Ward). A few days later, her father’s cousin came looking for them, and they traveled by truck to the village of Tusuga (today’s Akiota Town in Hiroshima Prefecture) where her father’s parents lived. Shortly after, her father’s hair began to fall out and his gums started to bleed. While worrying about his daughter, who had suffered serious injuries, he passed away on August 22.

Ms. Noboritate herself suffered from a high fever for some time. By November, she had recovered enough to walk with a cane, and she returned to the city of Hiroshima with her mother, relying on her mother’s relatives for support.

In the spring of 1946, she graduated from high school. On a teacher’s recommendation, she went on to Hiroshima Jogakuin Vocational School (today’s Hiroshima Jogakuin University). At the age of 22, she got married and then had a son. When she was 37, she was asked by people in her community to serve as a volunteer social worker, and she worked to turn around troubled youth for the next 40 years.

Due to the damage suffered to her right knee, for a while she was unable sit in traditional seiza style, with the legs bent behind. She also endured a period when she could not walk in a natural fashion, and she heard some unkind words from others. As she grew older, her knee became so painful that she had trouble sleeping at night. After undergoing surgery in the fall of 2011 to replace the joint with an artificial implant, she can finally walk without pain.

“The wounds left by the atomic bombing have lingered our whole lives,” Ms. Noboritate said, stressing her words. “If a war is about to break out, I would do anything to prevent innocent children from suffering the same misfortunes.” (Sakiko Masuda, Staff Writer)

Hiroshima Insight

Hiroshima First Municipal Girl’s School: Words “atomic bomb” not permitted for monument

Hiroshima First Municipal Girl’s School (today’s Funairi High School in Naka Ward) is known as the school which suffered a greater death toll in the atomic bombing than any other school in the city.

On August 6, 1945, all of the 541 first- and second-year students (ages 12 or 13) and seven teachers who were helping to dismantle buildings to create a fire lane in the Kobikicho district (part of present-day Nakajimacho in Naka Ward) perished in the blast. Including the older students and other teachers who died elsewhere in the city, the school lost a total of 676 members of its community.

In 1948 a memorial was erected on the school grounds. The figures of three girls have been engraved on this monument, and the girl in the center is holding a box with the equation “E=mc2”--the formula for the theory of relativity. When the monument was constructed, Japan was still occupied by Allied Forces and so the words “atomic bomb” could not be used at the time. Because people were unable to speak freely about the damage caused by the bombing, the theory of relativity, which led to the creation of the atomic bombs, was engraved on the monument instead.

In 1957, the monument was moved to its present location at the west end of Peace Bridge, in the green belt along Peace Boulevard, near Peace Memorial Park. This was roughly the area where the students from Hiroshima First Municipal Girl’s School were carrying out their work assignment that morning, helping to create a fire lane, and were killed.

Hiroshima First Municipal Girl’s School closed in 1948, then was reborn as Funairi High School.

Teenagers’ Impressions

I won’t discriminate against anyone

Sometimes people said unkind things about Ms. Noboritate, whose leg was badly damaged in the bombing. Each time she thought, “I wish I had my old leg back.” She must have felt such distress, she couldn’t help making this wish. It’s important that we don’t discriminate against other people. I intend to treat everyone the same, and make more friends. (Ishin Nakahara, 15)

Make compromises and forgive one another

“It’s important to make compromises and forgive one another.” These were the words of Ms. Noboritate, who worked for a long time as a volunteer social worker. If everyone behaved with this thought in mind, we could solve most of the conflicts occurring in the world today, and new conflicts wouldn’t break out. In my case, I’ll try not to be too assertive, and I’ll try to maintain good relationships with the people around me. (Yuka Iguchi, 18)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

While attending a vocational school, Ms. Noboritate underwent surgery to repair the damage to her right knee, injured in the atomic bombing. But the operation didn’t go well. Later, she visited an osteopath to massage the leg, and it took a year for her to be able to sit seiza style again. She made her mother’s dream come true, though, when she wore a formal, long-sleeved kimono and could take part in a tea ceremony. Still, the injury didn’t heal completely. As a result of the damage she suffered to her knee, her right leg became two centimeters shorter than her left leg, and she can’t walk for extended periods of time. She was forced to give up her dream of climbing Mt. Fuji.

Because she didn’t want others staring at the prominent scar on her left shoulder, she wouldn’t wear sleeveless blouses and swimsuits. She experienced no discrimination when it came to marriage, but when she had her first child, she made sure that the baby had five digits on each hand and foot. During our interview, she murmured, “What if I hadn’t experienced the atomic bombing, what kind of life would I have had?” Ms. Noboritate lost her father and her good health in the atomic bombing. War, and the atomic bomb, stole these things from an innocent person. (Sakiko Masuda)

(Originally published on January 13, 2014)