History of Hiroshima: 1945-1995 (My Life, Part 7)

Aug. 1, 2012

My Life, Part 7: Tadao Hamada, 66

by Yoshifumi Fukushima, Staff Writer

A-bomb doctor

Thirteen hours after his father’s pulse had stopped, the body was, at dawn, placed on an autopsy table at the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital & Atomic Bomb Survivors Hospital. Tadao Hamada, serving as his father’s doctor, held a scalpel. With one stroke, Dr. Hamada made an incision of about 70 centimeters downward from under his father's chin. Blood that had not yet clotted oozed from the cold body. A staff member wrote in the autopsy record: “Tonso Hamada, 73.” The father, who was an A-bomb survivor, had told his son before his death: “Use my body for your research.”

Dr. Hamada performed pathological autopsies on about 2,000 bodies, including A-bomb victims, at the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital & Atomic Bomb Survivors Hospital, where he worked for 20 years from 1965. He conducted an autopsy every three days, in addition to providing medical treatment as a physician. “I wanted to leave as many records of autopsy cases of A-bomb victims as possible,” said the aging doctor, no longer at the forefront, as he spoke of his persistence in pursuing research involving A-bomb-related medicine.

Dr. Hamada's brutal experience of the atomic bombing set him on the path to study medicine. He was a first-year student at the former Hiroshima High School at the time, and he was exposed to the bomb while riding in a streetcar at a spot 750 meters from the hypocenter. In the aftermath of the bombing, his hair fell out and he suffered a high fever which precipitated days of faint consciousness. His white blood cell count fell and his gums were rotting. Two years later, he had an operation on his left eye for a cataract induced by the bombing. Still, he had no reservations about choosing a career in medicine. During the ten years he spent at the Faculty of Medicine at Kyushu University, he did research on leukemia, prompted by his anger over the atomic bombing.

The field of pathological autopsies does not garner much attention. However, cures for disease cannot be sought without the knowledge obtained through pathological autopsies. The Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital & Atomic Bomb Survivors Hospital did not accrue many records of pathological autopsies in the 20 years following the atomic bombing. For this reason, Dr. Hamada devoted his energy to performing autopsies.

His father's autopsy was part of Dr. Hamada's efforts. His father, who was suffering from arteriosclerosis and an early stage of lung cancer, was undergoing medical treatment at home. He died suddenly, however, when an IV was being administered. The autopsy revealed bleeding in his stomach, but no clear correlation was made between the atomic bombing and his symptoms. Dr. Hamada wrote down his detailed observations of the autopsy as the 443rd “autopsy case” at the hospital. The date was July 9, 1966.

“It's cruel to cut the dead,” Dr. Hamada confided. “Unless you let go of your feelings and focus single-mindedly on investigating the cause of death, you cannot perform an autopsy--particular if the dead person is your father.” The internal organs that were removed from his father's body were sliced and transformed into specimens on glass plates two months later.

A general trend exists with regard to the effects of radiation released by the atomic bomb. Shortly after the bombing, there was a spike in the incidence of leukemia; now, thyroid, lung, and breast cancers are occurring frequently as well. With the number of A-bomb survivors who experienced direct exposure to the bombing on the decline, obtaining pathological data for these people upon their death is vital.

“I haven't done so many autopsies,” Dr. Hamada said. “But if we collected the autopsy records from all the hospitals in Hiroshima, maybe we can say something about the effects of radiation.”

Dr. Hamada is hoping young doctors will emerge who will conduct research on A-bomb-related medicine with the use of these pathological specimens. “But in the field of medical research, too, quick outcomes are now required,” he said. “Researchers jump at novel themes. The work which involves steady efforts to do basic research may not be suited for young people today.”

Dr. Hamada is one of the “second-generation” A-bomb doctors following in the footsteps of doctors and other medical personnel who were engaged in the treatment of patients in the aftermath of the atomic bombing. A sense of duty, borne from the feeling that “I've been given the chance to live to do something constructive,” has continued to provide a push from behind. If the street car that Dr. Hamada was riding in had come 100 meters closer to the hypocenter when the bomb exploded, he would have perished in the blast.

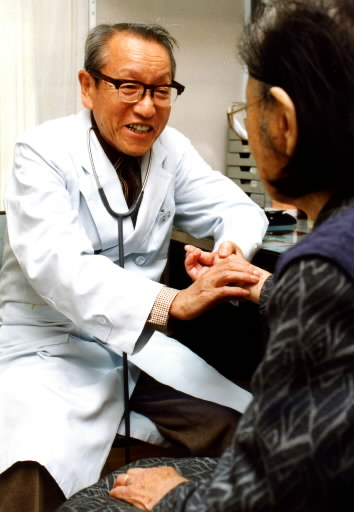

At the end of 1985, Dr. Hamada retired from his position as director of the Clinical Laboratory at the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital & Atomic Bomb Survivors Hospital. He then began to practice general medicine and now examines elderly patients and others. He has not conducted an autopsy since leaving his previous role, but he maintains confidence in his skill. “However,” Dr. Hamada said, “I don't think I would have been able to perform an autopsy on my mother, even if I had been an active doctor at the A-bomb Survivors Hospital.” His mother, also an A-bomb survivor, died five years ago at the age of 92. She was bedridden due to rheumatism and osteoporosis and had wasted away to skin and bones. “I felt so sorry for her...” Dr. Hamada said. The eyes of the A-bomb doctor, now a good-natured old man, quickly turned red with tears.

Memo

As of December 31, 1994, the number of pathological autopsy cases at the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital & Atomic Bomb Survivors Hospital totaled 3,378. The number of autopsies is on a downward trend across Japan, due to a lack of doctors skilled in conducting autopsies and the improvement of testing equipment. However, the autopsy cases of Japanese hospitals are compiled annually by the Japanese Society of Pathology and published as the booklet “Nihon Byori Boken Shuho” (“Pathological Autopsy Cases in Japan”).

(Originally published on January 9, 1995)