History of Hiroshima: 1945-1995 (Part 2, Article 2)

Aug. 1, 2012

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Ceremony

by Masami Nishimoto, Staff Writer

Note: This article was originally published in 1995.

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park stretches across the center of a delta in Hiroshima, a city of rivers, with Peace Boulevard running alongside the park. When standing on the 100-meter-wide boulevard, facing Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims and the Atomic Bomb Dome can be seen standing along a straight axis to the north. From that spot, when silence prevails, the cry of the A-bombed city of Hiroshima can be heard.

This is where the hypocenter lies, where a single atomic bomb annihilated everything. From utter ruin, the site was transformed into the park, with an area of some 122,000 square meters, and its memorial facilities, becoming a place for the vow of seeking a lasting peace.

Two young artists, Kenzo Tange and Isamu Noguchi--Japanese and American, respectively--devoted all their skill and passion to realizing this grand project. However, the effort to construct the park was buffeted by public opinion and the passions of the day. Meanwhile, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Ceremony was marked by pressure exerted by the occupying forces. In this article, the Chugoku Shimbun will explore part of the untold history involving the rebirth of Hiroshima as the A-bombed city, including the appeals that lay behind this rebirth.

Pressure from occupying forces results in cancellation of peace ceremony in 1950

The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Ceremony is held in the city of Hiroshima each year on August 6, the day of the atomic bombing. The current ceremony dates back to the first Hiroshima Peace Festival held in 1947. The ceremony, which has continued to appeal for a world without nuclear weapons and war, was suspended just once. In 1950, when Japan was under Allied occupation, the ceremony was canceled. Why wasn't the peace ceremony held that year? The Chugoku Shimbun will examine the background behind this gap in the history of the Peace Memorial Ceremony.

The cancellation came abruptly. On August 2, just prior to the fifth anniversary of the bombing, a meeting of the standing committee of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Service Committee was held at Hiroshima City Hall, which still bore scars from the blast. The 24 people in attendance that day quickly agreed to cancel the Hiroshima Peace Festival.

The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Service Committee was comprised of several entities, including the City of Hiroshima, the Hiroshima Chamber of Commerce and Industry, a neighborhood association, and a cultural organization. The mayor of Hiroshima served as president. If the Peace Memorial Ceremony were to be canceled today, it would cause quite a stir. However, the next day the newspaper printed only a perfunctory comment on the cancellation, which was made by the deputy mayor of Hiroshima, Tatsuro Okuda, on behalf of the mayor, who was on a business trip.

“For certain reasons, the committee has decided to cancel the ceremony on August 6,” the comment read. “We hope that all citizens of Hiroshima will spend August 6 in a reverent day of reflection and prayer.” But what are those “certain reasons” vaguely phrased in the statement?

According to documents preserved by city hall, the committee that day heard a “report on the developments of negotiations at the civil affairs bureau” and “canceled the peace ceremony to address these new circumstances.” The civil affairs bureau, located in the city of Kure in Hiroshima Prefecture, was the authority of its kind for the whole of the Chugoku region. The bureau, which was directly connected to the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ), watched over the orders made by the occupying forces and reported to the GHQ how those orders were being carried out by Japan.

Chimata Fujimoto, 76, a resident of Hiroshima who attended the committee meeting as chief-of-staff of the mayor's office, explained the significance behind the phrase “certain reasons.” “We couldn't openly say that the occupying forces made a complaint about the ceremony, you know,” Mr. Fujimoto said. “When they told us to cancel the ceremony, we had no choice but to do so.”

As far as Mr. Fujimoto recalls, there was no detailed explanation at the meeting from Mr. Okuda, who had conducted the negotiations with the civil affairs bureau. No one questioned Mr. Okuda about the matter, either. The fact that there were “new circumstances,” which actually involved Allied objectives related to the Korean War, was enough for those in attendance. “The mindset before the war, where people just followed along with what their leaders said, still lingered,” Mr. Fujimoto said.

On June 25, war had broken out on the Korean Peninsula. Two days later, U.S. forces stationed in Japan were dispatched. At that point, demonstrations and gatherings had already been banned. In July, Douglas MacArthur, then Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, assumed the post of Commander-in-Chief of the United Nations Command. As the war spread, there was talk by the United States and the Soviet Union about using the atomic bomb and Cold War tension between East and West rose sharply.

Amidst these circumstances, Hiroshima Mayor Shinso Hamai, president of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Service Committee, was away in Switzerland. He had been there since June 14 to take part in the global meeting of the Moral Re-Armament Movement (MRA), an international peace movement seeking to restore moral behavior, which was proposed by the Reverend Frank Buchman, an American pastor. Among the 48 Japanese participants was the young Yasuhiro Nakasone, a member of the House of Representatives.

Shinso Hamai, the “A-bomb Mayor” of Hiroshima, was asked about his view on the atomic bombing wherever he went. On July 16, he was interviewed by Le Monde, a leading newspaper in France, and said: “I will speak out loudly against the use of an atomic bomb in Korea.”

Mr. Hamai's remark also appeared in newspapers in Japan, where censorship was imposed by the GHQ. However, on July 24, the Red Purge of those whom the GHQ considered a threat extended to the media as well. Perhaps due to this development, the tone of the Chugoku Shimbun, compared to the preceding year and years past, changed dramatically when it came to the cancellation of the peace ceremony. An article from the August 6, 1950 edition of the Chugoku Shimbun contained the following comment: “Even if we don't hold a boisterous event this year, the feelings of the citizens of Hiroshima are well understood.”

After departing Europe, Mr. Hamai traveled across the United States and received news of the cancellation of the peace ceremony while in Los Angeles. On August 6, an event dubbed “Hiroshima Evening,” which was organized by MRA, was attended by the mayor of Los Angeles and others. Mr. Hamai was invited to this dinner party as a guest speaker.

In his address, Mr. Hamai said, “We, the citizens of Hiroshima, hold no grudge against anyone now. I would like to say that we hope people everywhere will learn what happened in Hiroshima and will make efforts so that such a thing will not happen again anywhere else.”

Mr. Hamai spoke for over 20 minutes and his speech was broadcast live across the United States by CBS radio. Sen Nishiyama, 83, a resident of Tokyo who would later be known for his simultaneous interpretation of the moon landing by the U.S. spacecraft Apollo, among other interpreting work, served as interpreter on this occasion. He had taken a leave of absence from his duties at the GHQ's Civil Communication Section to accompany the mayor and his delegation on their trip. “Mayor Hamai's speech, though carefully worded, was filled with the feeling that an atomic bomb must never be used again,” Mr. Nishiyama said. “The speech touched the hearts of the audience, who responded with applause.”

It was an appeal against the atomic bomb in the nation that had celebrated the victory of democracy in World War II, believing that “the atomic bombing had led to the early end of the war.” Mr. Nishiyama has a vivid memory of the mayor racking his brains so that his statement about the bombing would not take on a tone of criticism against the United States. The interpreter, who was born in the U.S. state of Utah and completed graduate school there, also took special care in his handling of the mayor's address. Prior to the event, he read a copy of the speech and made a full translation of the text, which he read out.

This is how carefully Japan was forced to tread in 1950, five years after the nation's defeat in World War II.

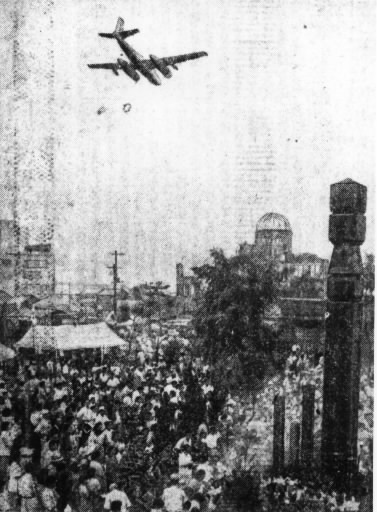

After that summer without a formal ceremony, Hiroshima's peace ceremony resumed the following year. On the morning of August 6, 1951, a U.S. military aircraft flew over the hypocenter and dropped a wreath of flowers on the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound. Twenty-four pilots who would make sorties in the Korean War attended the ceremony, invited by Hiroshima Prefecture and other entities. Today, it is impossible to even imagine such a thing occurring at the ceremony. It seems there was a request from the U.S. Marine Corps Air Station in Iwakuni, Yamaguchi Prefecture, to extend an invitation to these pilots.

The current form of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Ceremony, as well as the appeal made by the A-bombed city of Hiroshima, were shaped through the twists and turns of this deeply-troubled past.

Harushi Ishijima, chief of NHK Hiroshima Central Broadcasting Station, proposes holding a peace ceremony in Hiroshima

In 1955, Mayor Hamai revealed in his book entitled “Hiroshima Shisei Hiwa” (“The Untold Story Behind the City’s Administration”) that it was Harushi Ishijima, the chief of the NHK Hiroshima Central Broadcasting Station, who proposed that a peace ceremony be held in Hiroshima.

At a meeting of the Tourism Association of the City of Hiroshima, which was reestablished in 1947, Mr. Ishijima, one of the members of the association, said, “I believe that holding a large-scale peace festival, focused on August 6, will enable us to make a strong appeal for peace to the public, including people around the world.” In June of that year, the Hiroshima Peace Festival Association, the forerunner of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Service Committee, was born and Mr. Ishijima assumed the post of vice president.

The first peace ceremony was broadcast live in Hiroshima Prefecture by radio. It started at 8 a.m. and lasted 30 minutes. According to the “NHK Hiroshima Hosokyoku 60 Nen Shi” (“Sixty-Year-History of the NHK Station in Hiroshima”), the ceremony began to be broadcast live nationwide from the following year. Until June 1950, when he left Hiroshima due to a company transfer, Mr. Ishijima played a leading part in spreading the facts of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima throughout Japan.

“Ever since he was young, my father had an idealistic streak,” said Haruo, 68, Mr. Ishijima's oldest son and a resident of Tokyo. Mr. Ishijima was born in Kagoshima Prefecture and formed a friendship with Yoshio Shiga, among others, when he was a sociology student at the University of Tokyo. He was also involved in the Settlement Movement, which sought to help the poor.

Haruo, then a student at the Hiroshima School of Secondary Education (now, Hiroshima University), said that he and his father discussed his father's idea of holding a peace festival. When Haruo expressed some concern, saying, “An event like that may rub the feelings of the A-bomb survivors the wrong way,” his father shared this sentiment: “We must not let the atomic bombing fade from memory.” Haruo continued, “My father was also enthusiastic about broadcasting the ceremony, describing it as part of 'the mission of a broadcaster.'”

During his life, Mr. Ishijima never failed to offer a silent prayer on August 6. He died a peaceful death in 1992 at the age of 93.

Tsunenori Mano, a resident of Hiroshima Prefecture, dedicates 100,000 paper cranes from the sky

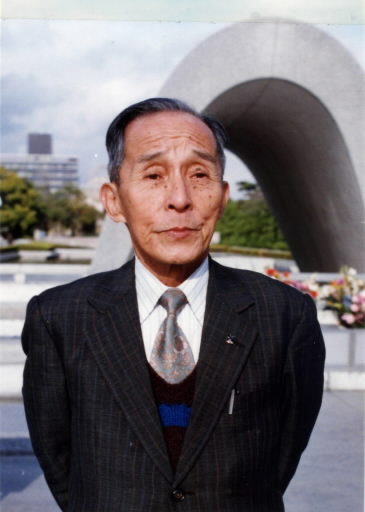

“Yes, that was definitely me,” said Tsunenori Mano, 73. A newspaper article that relates the peace ceremony in Hiroshima in 1962 reads: “Paper cranes in flight over Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park.” The article reports that someone dedicated as many as 100,000 paper cranes, all folded himself, to the venue of the peace ceremony by releasing them from a Cessna plane.

Mr. Mano's wife Kimie lost five out of seven family members in the atomic bombing, including her parents and brothers. Mr. Mano, who married Kimie after he was discharged from the military in Guangzhou, China, also lost relatives, including an uncle. “War must not be waged again,” he said. “It was that feeling that inspired the project.” He bought a paper cutter to make suitable squares of paper for folding. He folded the paper cranes during his days off from work and while commuting to and from his office on the train, about 50 minutes one-way from his home in the town of Kake in Hiroshima Prefecture, where he still resides. It took him three years to finish folding 100,000 paper cranes.

August 6, 1962 was a fine, clear day. It was the first time he had ever boarded a Cessna plane, and he had spent a sum equivalent to one month's salary to hire the aircraft. At 8:30 a.m., right after the ceremony ended, the plane began circling above Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. The plane circled once, twice, and the paper cranes that he had imbued with his wish for peace took wing over the heads of the 30,000 people attending the ceremony.

“I went back to Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park with my wife, who was waiting for me at the airfield,” said Mr. Mano. “Strangely enough, we didn’t find even a single paper crane. The people picked them up. I was really moved.”

Kimie died of cancer in 1975 at the age of 49. Mr. Mano has become concerned that the ceremony now lacks the sort of substance it once had. “The peace ceremony these days has become a hollow form of what it once was. The fact that people fret over whether or not the prime minister will attend the ceremony is worrying to me.” Mr. Mano simply watches the peace ceremony on television now.

[References]

“Isamu Noguchi: Essays and Conversations,” published by Harry Abrams Inc.

“Noguchi,” written by Bruce Altshuler

“Amerasia Journal,” published by UCLA.

(Originally published on January 29, 1995)