History of Hiroshima: 1945-1995 (Part 4, Article 2)

Aug. 1, 2012

Medical Care in the Early Aftermath of the Bombing II

by Tetsuya Okahata, Staff Writer

Note: This article was originally published in 1995.

“I will follow that system of regimen which, according to my ability and judgment, I consider for the benefit of my patients.” Hippocrates, the legendary doctor of ancient Greece, made this oath to himself. I don’t believe I’m the only one who is deeply moved, linking this oath, which has been handed down from generation to generation as the finest of medical ethics, to the doctors and nurses who have dedicated themselves to relief efforts in the aftermath of the Great Hanshin Earthquake.

The same thing also occurred in Hiroshima 50 years ago. Despite their own suffering, a large number of doctors stayed true to this oath through the aftermath of the atomic bombing, a calamity confronting human beings for the first time in history, and would later fall ill themselves, sometimes fatally. Even the taboo involving A-bomb-related issues during the period of occupation did not deprive doctors of the passion with which they sought to learn the truth of unknown A-bomb diseases.

The Chugoku Shimbun now looks at the “oath” of the A-bomb doctors, concentrating on the “Tsuzuki Group of the Department of Surgery at the University of Tokyo,” which played a leading role in A-bomb-related medicine early on, and “doctors in the A-bombed city of Hiroshima,” who have strived to treat the aftereffects of the atomic bombing under circumstances that could be called a vacuum of medical care.

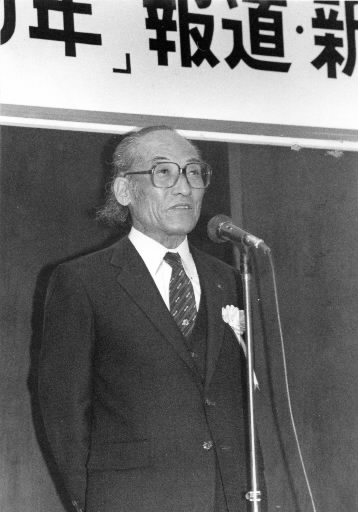

With sense of mission, surgeon confronts aftereffects of the atomic bombing

On a winter night, four years after the atomic bombing, Dr. Tomin Harada, now 82, gasped at the face of the boy, lit by candlelight. It was on that night, the night of a blackout, that the fate of doctors in the A-bombed city of Hiroshima clearly struck Dr. Harada, a surgeon of Naka Ward, Hiroshima.

The boy, Kenji, who had been carried to Dr. Harada on his father’s back, was wasting away. Though he was five years old, he looked barely more than a year and a half. His head, though, was unusually large. A closer look revealed a lump on his head and oozing pus. Dr. Harada made an incision on the boy’s ear to perform a blood test, but no blood would come. When Dr. Harada moved the candle closer to the incision, he saw a pale yellow secretion flowing instead.

The boy was exposed to the atomic bombing while in his baby carriage in the Enoki area, about 800 meters from the hypocenter. After the blast, he developed a persistently high fever and his hair fell out. Since that time, the boy never regained his health. The father said that the lump on his son’s head was the result of a fall down the stairs suffered by the boy six months earlier. When the electricity was restored after the blackout, Dr. Harada peered through a microscope and found that Kenji’s white blood cells had grown to an alarming size. The word “leukemia” flitted across his mind.

Surgeons are rarely involved in cases of leukemia. Dr. Harada remembered that less than ten minutes was given to the subject of leukemia during the lectures he attended at medical school. With a microscope slide in hand, which held the boy’s blood, he visited the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC) in Ujina, the southern district of the city. A young pathologist from the United States confirmed that Kenji had leukemia. Dr. Harada was then taken aback by what the pathologist said next. He said that he had been waiting for this disease to develop.

Radiation from an atomic bomb, and particularly the neutrons, destroys bone marrow and leads to leukemia. The pathologist said that he had been dispatched to Hiroshima due to the possibility that the number of leukemia patients would rise. And as the pathologist had predicted, there were nearly 300 people suffering from leukemia, with the number of patients reaching its peak in 1950. Dr. Harada felt a chill run down his spine.

Soon after, the boy and his father left Hiroshima. Dr. Harada heard that Kenji’s father took him to his grandmother’s house in another town, as he wanted a decent home in which his son could die. A few days later, Kenji passed away. Only four people attended the funeral. On his death certificate, the cause of death was listed as “pneumonia.”

“I felt miserable,” Dr. Harada recalled. “It was then that I decided to devote my whole being to combating A-bomb diseases.” Over the next three years, he detected seven more cases of leukemia.

In the spring of 1946, the year after the bombing, Dr. Harada, who had served as a military doctor, returned to Hiroshima. In November, he built a shack in the ruins of the fire that had razed the Hirose area and began to practice medicine there. Around that time, military doctors who were discharged from their military service and other medical practitioners gradually began establishing small clinics across the city. The acute symptoms of the bombing, suffered by A-bomb survivors in the aftermath of the blast, tentatively subsided, but the aftereffects of the bombing were quietly building.

One of these aftereffects is called a keloid. Keloids form on burned skin as raised and hardened scars. Even when the keloid is removed and other skin is grafted to that spot, the keloid scar soon reappears. “Isn’t this a kind of A-bomb disease?” Dr. Harada wondered, with an ominous feeling, as he sought to develop methods of treatment through trial and error.

This was a time when the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ) exerted strict control over information in order to maintain secrecy in connection with the atomic bombs. The medical field was no exception. Valuable research data that had been gathered in the wake of the bombing was also confiscated by U.S. forces. The doctors of the A-bombed city were forced to face A-bomb diseases with little knowledge or data to guide them.

In the second autumn after Dr. Harada opened his clinic, he heard from an older doctor, a gynecologist, that an anencephalic baby had been born. “What sorts of tragedies are buried in this A-bomb desert?” thought Dr. Harada. That weekend, eight doctors with different specialties gathered to meet. The “Doyokai” (“The Saturday Club”) was launched.

“One patient unexpectedly died due to an operation for appendicitis,” a doctor said. “What is this unusual fatigue some patients are experiencing?” another wondered. The membership fee for the group was 100 yen [then about 27 U.S. cents]. Until late at night at a member’s house, the doctors would eagerly listen to reports outside the realm of their specialties and engage in discussions based on what little data they had.

These discussions of the Doyokai led Dr. Gensaku Oho in the Midori district to research the development of cancer in A-bomb survivors two years earlier than ABCC, and Dr. Hiromi Nakayama in the Danbara area to devise a health book for A-bomb survivors and start to care for the health of A-bomb survivors in his neighborhood.

Dr. Harada recalled: “ABCC said that the idea of linking cancer with the atomic bombing was laughable. After Dr. Oho made a presentation on the subject in Nagasaki, ABCC hurriedly began its own investigation. I found that gratifying.”

In 1952, it was decided that a group of young women who were A-bomb survivors would receive medical treatment at the University of Tokyo and Osaka University. Dr. Harada was asked by a reporter for his comments on this development. When the reporter spoke in a tone that Dr. Harada took for an accusation, questioning why the women could not be treated in Hiroshima, he became incensed. Afterwards, he shared this conversation with Kaoru Shima, who happened to be riding in the same car and was the director of Shima Hospital, where the hypocenter of the bomb was located. “As surgeons of Hiroshima, we couldn’t put up with that sort of mindset,” Dr. Harada said.

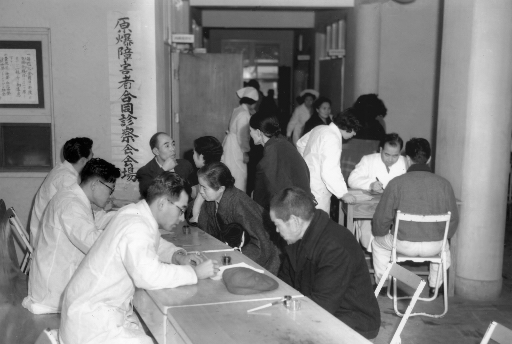

This was right after the peace treaty with the United States took effect and the press code was lifted. Doctors in Hiroshima united under the slogan: “No one else but us will treat A-bomb survivors.” Based on a study of the damage to A-bomb survivors’ health that was conducted by the City of Hiroshima in 1952, the doctors carried out medical examinations free of charge. The following year, the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Casualty Council, which would serve as a body to promote the medical care of A-bomb survivors, was established.

“Doctors in the A-bombed city of Hiroshima have never been more passionate than they were at that time,” Dr. Harada said. “Now that I think of it, it was because of our strong will and pride when it came to the United States. We were determined to treat A-bomb diseases ourselves.” The doctors’ unity eventually proved a significant factor in paving the way for the enactment of the Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law in 1957.

The medical care of A-bomb survivors, which began from scratch, came to a culmination with the establishment of the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Casualty Council. However, this turned out to be simply the prelude to a long, hard struggle for doctors in the A-bombed city.

[Brief History] Doctors engage in relief efforts in Hiroshima without sleep or rest

As many as 225 physicians died in the performance of their duties as a result of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. Three-fourths of the doctors who were in Hiroshima at the time fell prey to the bombing. The medical infrastructure of the city broke down instantaneously.

Doctors and nurses, among others, narrowly escaping death themselves, plunged into relief activities before thinking of their own injuries. As if in response to these dedicated efforts, medical teams entered the city one after another from other parts of Hiroshima Prefecture as well as from other prefectures. On August 7, a medical team from Okayama Prefecture arrived in Hiroshima, and doctors from Shimane, Yamaguchi, Tottori, Hyogo, and Osaka prefectures, among other regions, continued to provide aid without sleep or rest.

From the unprecedented damage in the city, Japanese military authorities intuitively felt that the cause was an atomic bomb, and sent teams to investigate soon after the blast. A team from the Kure Naval District arrived in Hiroshima on August 6, while teams from the Navy, the Technology Agency, the Imperial Japanese Army, and the Army Ministry arrived on August 8 and those from Kyoto University and Osaka University arrived on August 10.

On August 10, the joint study group from these teams of investigators, including Dr. Yoshio Nishina from the Institute of Physical and Chemical Research, concluded from an X-ray image that was exposed to radiation that the city had been attacked with an atomic bomb. On that day, Kiyoshi Yamashina, a lead surgeon on the team from the Army Ministry, conducted an autopsy on an A-bomb survivor, the first such autopsy performed. The initial investigation was primarily intended to confirm whether or not an atomic bomb had been used and to consider interim defensive measures.

The full-blown investigation with an eye to providing medical treatment for A-bomb diseases began with the August 30 arrival of a team from the University of Tokyo, led by Professor Masao Tsuzuki. Though Kyoto University also sent a team to conduct a probe on September 5, that team was nearly killed by a landslide triggered by a typhoon that had struck on August 17. Around that time, the chaos which followed the bombing ebbed and the medical treatment of A-bomb survivors began full swing. On October 5, the number of first-aid stations was reduced from 53 to 11, while hospitals run by the Japanese Medical Team opened in six locations.

Four months after the bombing, most of those who suffered severe injuries in the blast had passed away, while the survivors who bypassed death appeared to be improving. Instead of the acute symptoms which characterized the immediate aftermath, the bombing’s aftereffects now began to appear. Typical among these aftereffects were leukemia, keloid scars, and A-bomb cataracts.

Though their activities were restricted by the press code put in place by the Allied forces, Japanese doctors worked steadily on medical treatment and research. After the peace treaty went into effect in 1952, the results of their efforts brought a succession of achievements into the light of day, including the revelation made by Dr. Takuso Yamawaki, of Naka Ward, Hiroshima, involving the link between the atomic bombing and leukemia. Since that time, doctors have been facing the occurrence of various cancers in the survivors.

Article in the Chugoku Shimbun on September 8, 1945

“Miraculous effects” of moxibustion “proved” through experiments on patients

With no perfect cure available for A-bomb diseases, a range of folk remedies became popular in the aftermath of the atomic bombing. For A-bomb survivors who were desperate for any help at all and clung on to hope, “moxibustion” was one of these typical remedies. On September 8, 1945, an article appeared in the Chugoku Shimbun with the headline: “Burn moxa on your skin now: Miraculous effect on A-bomb diseases.” This article read as follows:

Masato Tsutsumi, deputy chair of the Acupuncture & Moxibustion Association in Saeki District, Hiroshima Prefecture has treated sufferers of the atomic bombing and his experiments on a large number of patients have proven that moxibustion has a miraculous effect on A-bomb symptoms.

Among the dozens of patients Dr. Tsutumi has treated, three have already been cured completely. Four others are considered, with certainty, to be heading toward a complete recovery. And the remaining patients are all improving, including four or five suffering from such severe symptoms as a high fever of more than 40 degrees Celsius, spots that appeared all over the body, and hair loss. As Professor Tsuzuki has demonstrated, moxa treatment has the effect of preventing damage to white blood cells and red blood cells and aiding in the process of these cells increasing in number.

[Reference] “Warrior without Weapons” by Marcel Junod

(Originally published on February 12, 1995)