History of Hiroshima: 1945-1995 (Part 6, Article 1)

Aug. 1, 2012

A-bomb Orphan

by Masami Nishimoto, Staff Writer

Note: This article was originally published in 1995.

The atomic bombing not only stole away the lives of so many in an instant, it also forced the survivors to endure difficult lives from that point forward. After the war, orphans and young women, in particular, were plagued with days of hardship. Even after many citizens of Hiroshima were able to find peaceful lives, the atomic bombing weighed heavily on such survivors. As the years passed, most of the orphans and young women, who were beset by severe mental and physical scars and adversities, became tight-lipped in the face of the thoughtless stares of the public.

“What difference will it make if I talk about it now, after all these years?” “I’m fed up with the atomic bombing and the media.” When I came into contact with those who were once called “A-bombed orphans” and “A-bomb Maidens,” a striking number of them refused my request for an interview. Even 50 years after the atomic bombing, the lingering wounds in their hearts have not healed. Under these circumstances, the Chugoku Shimbun took up the task of tracking the life of an orphan who twice survived the ravages of war, in Japan and South Korea, and the “Hiroshima Girls,” who traveled to the United States to receive medical treatment for their keloid scars. This report was motivated by our abhorrence of war and the atomic bombing, which have brought misery to the most vulnerable.

Norihiro Tomoda, A-bomb orphan, survives struggles of youth

I found the man I had been seeking in Joto Ward in the city of Osaka. His thin face appeared much younger than the 60 years he would turn this December.

The atomic bombing of Hiroshima left him an orphan and led to a move to South Korea. Fifteen years later, he returned to Japan. Norihiro Tomoda, now 59, sat down to tell me the whole story of his life to date, as he did not buckle under to the numerous hardships and struggles of his youth.

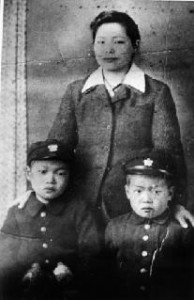

“When I returned to Japan and saw the Buddhist altar at which my grandmother used to pray, I found this photo,” he said with a laugh. In the enlarged black-and-white photo, Mr. Tomoda is with his mother Tatsuyo, who was 30 years old when she perished in the bombing, and his younger brother Sachio, who was eight at the time. It was a portrait of family members whose remains were never found.

The hypocenter of the blast is an area that figured in a score of childhood memories. His parents’ home was located in the Otemachi district. Though his father Taichi died of illness when Mr. Tomoda was small, his mother was a hardworking woman. Tatsuyo, who took over the family’s tailoring business, still took the time to go boating with her son on the Motoyasu River near their home. In summer, Mr. Tomoda would go swimming in the river, the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall (now, the Atomic Bomb Dome) looming above him on the bank. And he attended Fukuromachi Elementary School, less than a ten-minute walk from his house.

He experienced the A-bomb blast while at school. “I was in the fourth grade,” he said. “That day I was late for the morning assembly. When I was hurrying down to the basement, where the shoe cubbies were located...” Before he knew it, he was dashing between flames and dragging along his right leg, pelted by glass fragments from an exploding skylight. He made to flee with classmates who had also been in the basement when the blast hit. Those who were in the school yard at the time, including his younger brother, were burned black.

For days, Mr. Tomoda wandered through the city, now reeking of death, in search of his mother. He also dug through the rubble where his house had once stood. At a loss, he looked for a man named Saburo Kanayama, who had been renting a room on the second floor of their house. To the eyes of a child, Mr. Kanayama appeared to be about 40 years old. He was at work when the bomb exploded, but he survived the blast, too.

Together with Mr. Kanayama, Mr. Tomoda fashioned a shack on the bank of a river and began living there. But on September 17 Hiroshima was hit hard by the Makurazaki Typhoon, which left more than 2,000 people dead or missing, and their shack was washed away in the storm.

“He must have felt it would be cruel to leave me to fend for myself,” Mr. Tomoda said. “I guess that’s why he took me with him. I had no choice but to go, in order to survive.”

As it turned out, Kanayama wasn’t the man’s real name. His real name was Kim and Mr. Kim had come from the Korean Peninsula, which was under colonial rule by Japan. Mr. Tomoda had no idea that Mr. Kim’s homeland lay beyond the sea.

The two boarded a ship from the city of Moji in Fukuoka Prefecture. Docking in Pusan, they then took a train from Pusan to Seoul. At checkpoints along the route, Mr. Tomoda would repeat the single word that Mr. Kim had told him to say: “Aboji,” or “Father” in Korean. Though only a child at the time, Mr. Tomoda could imagine the ramifications if it was learned that he was actually Japanese.

His new name became Kim Hyeongjin.

Mr. Tomoda and “Aboji” went to live with the family of his elder brother, but the Japanese child’s presence provoked quarrels in the household. At school, too, he was bullied as soon as people discovered that he was Japanese.

With the boy in tow, “Aboji” left his brother’s home. He began making shoes with skills he had gained while in Hiroshima, and he married.

“His wife treated me kindly at first,” Mr. Tomoda explained, “but after she gave birth to her own child...” Feeling uncomfortable in the setting, he ran away. It was winter, and now, at the age of 13, he had no difficulty conversing in Korean.

He ended up on Yoi Island, which floats in the Han River as it flows through Seoul. Yoi Island, now home to the National Assembly Building and other large buildings, was then an airfield for U.S. forces in Korea. Mr. Tomoda polished the shoes of American soldiers there and wrapped himself in a woven-straw bag under a bridge at night. Word of mouth eventually brought him the news that “Aboji” had gone to North Korea.

In Korea Mr. Tomoda found comrades of a different nationality who had lost their own parents due to Japan’s invasion. He earned meals by running errands for a food stall at a marketplace. However, the apparent peace of his daily life was shattered all too soon by the Korean War, which broke out in June of 1950 and went on for more than three years.

Aided by Chinese troops, forces from North Korea pushed into Seoul on two occasions. Mr. Tomoda fled south to Daegu and staved off hunger by eating potatoes he dug from fields. The death toll from the war, involving noncombatants alone, exceeded one million.

In 1958, the fact that Mr. Tomoda was alive and living in Korea was conveyed to Japan. Letters that included Japanese katakana characters were received by the City of Hiroshima and Fukuromachi Elementary School. The letters arrived at a time no longer considered “the postwar period” by the people of Japan.

When I handed Mr. Tomoda an article with the headline “Longing for Home from South Korea,” which was printed in the evening edition of the Chugoku Shimbun on November 7, 1958, a wry smile appeared on his face. “The truth is, I had someone write those letters for me,” he said. Enduring those days alone in a foreign country, he had thoroughly forgotten his native Japanese.

After the “upheaval,” as Koreans dubbed the Korean War, Mr. Tomoda resettled in Seoul. The owner of a bakery to whom he had been delivering newspapers thought highly of his work ethic and offered him a job, and lodging, before he turned 20. On days off from the bakery, he paid visits to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in South Korea and asked them to let him return to Japan. However, he had no proof that he was Japanese. Though he held no documentation of Korean citizenship, either, he was nevertheless drafted into that nation’s military service for a time.

A part of him had already given up the idea of returning to Japan when he encountered the aid of a girl and her mother who worked at a market. “The girl’s name was Kin Chaesun,” Mr. Tomoda said. “She was three years younger than me.”

When they learned about his background, the aging mother took up a pen to write a letter in Japanese. Mr. Tomoda’s appeal, which would involve more than 30 letters, eventually pried open the doors of the Japanese and Korean governments, which did not have diplomatic relations at the time. Partly due to the earnest efforts of the mayors of Hiroshima and Seoul, Mr. Tomoda finally arrived home in Japan in June of 1960.

Though he was now back in Hiroshima, Mr. Tomoda had no remaining relatives apart from his maternal grandmother, who was 83 at the time. The City of Hiroshima helped him land a job at a local company that made bars of sweet bean jam and he sought to establish his independence. However, within a year he quit, but not because he was unhappy at work. “When I was in Hiroshima, I couldn’t help thinking of the days when my mother and younger brother were alive,” he explained. To shake that feeling, he moved to Osaka.

In 1965, Mr. Tomoda married Kayoko, now 55. A neighbor served as matchmaker. “After our first child was born,” Kayoko said, “he finally told me that he had experienced the atomic bombing and then lived in South Korea...”

“I was already 30 years old and I was afraid I wouldn’t be able to marry,” Mr. Tomoda said. “I felt rushed.”

As they recalled those days, the couple’s faces showed no signs of distress. The city of Osaka, known for the largest population of Korean residents in Japan, turned out to be a good fit for Mr. Tomoda.

All the more because there are gaps in his employment history, he neither drank nor smoked, and he worked himself to the bone. With his wife, four sons, and a daughter serving as inspiration, he also overcame the misfortune of a bankruptcy at the factory where he worked.

Mr. Tomoda has now climbed to a managerial role at Sankoh Kitchen Instruments, a factory that processes stainless steel kitchen components for restaurants and hospitals. He and his wife live in a two-room apartment in a municipal apartment building with one son, 26. “My only accomplishment was raising my five children,” he said, arriving at an age where he has come to feel the loneliness of an empty nest.

Still, said Mr. Tomoda, “Thanks to that family who wrote the letters for me, I was able to come back to Japan. I asked my younger brother to look out for them back in Korea.” His “younger brother” is a man he worked with at the bakery in Seoul. Since paying a return visit to South Korea 11 years ago, he has been traveling there often. He remains in touch with his “brother,” and the two consider one another siblings.

“My brother said that my pronunciation of Korean is even better than Koreans,” Mr. Tomoda said. “If I have the chance, I’d like to appear on TV in South Korea.”

This wish is partly because he has lost touch with Kim Chaesun and her mother, who enabled him to return to Japan. He would like to know what happened to them. At the same time, other long-lost friends in Korea might spot him on TV as well, leading to a reunion.

“The cruelty of war and the pain that orphans suffer are the same in any nation,” Mr. Tomoda said. “This sort of cruelty and pain has not only been caused by the atomic bombing. Those who haven’t actually lived through such an experience can’t really understand it, can they? Mr. Arashi faced the same struggles I did.”

His words touched me. Sadao Arashi was a classmate at Fukuromachi Elementary School. In the wake of the atomic blast, Mr. Tomoda fled with his friend from the basement of the school. Mr. Arashi, too, lost his entire family in the bombing. He went on to operate a sushi shop in the town of Tamayu in Shimane Prefecture. He passed away recently.

“I had no idea he died. I met him in Hiroshima about 25 years ago and he told me to come see him in Shimane...” Mr. Tomoda stood up, dabbed at his eyes, and left the room. I heard water splashing in the kitchen.

Former residents of orphans home gather to observe 50th anniversary of atomic bombing

The Hiroshima War Orphans Foster Home was a facility that took in orphans from the atomic bombing. The “moral adoption” campaign, by which U.S. citizens extended a helping hand to these children from overseas, both materially and emotionally, started here.

The Hiroshima War Orphans Foster Home opened in Saeki Ward four months after the bombing. After his discharge from military service, Gishin Yamashita, a missionary of the Honganji School of Shin Buddhism, used personal funds and created the home with his wife Teiko. Until January 1953, when the City of Hiroshima took over its administration, 171 children found shelter there. Growing up in the home, the children called the couple “Grandpa” and “Grandma.”

Those who lived at the Hiroshima War Orphans Foster Home all recall the love they felt from Mr. and Mrs. Yamashita and the other caregivers, along with the strict discipline expected of them. Children in the home would get up at the sound of the bell of Doshinji Temple, located at the same site. Each morning they chanted sutras then went off to school. As they rebuilt their lives as members of society, starting from scratch, they found emotional succor and formed their own homes in line with the moral principles they learned from the “Group of Doshin.”

Last August 6, about 50 people who had once lived in the home, now scattered across Japan, assembled after a long interval. At Hoonji Temple in downtown Hiroshima, they observed the 50th anniversary of the deaths of their parents, and held a Buddhist memorial service for their “Grandpa” and “Grandma.”

The head priest, Gojo Kubota, 80, and his wife Kimiko, 68, were both former staff members of the Hiroshima War Orphans Foster Home. Kimiko was a teacher at the Otemachi National School and joined the home with children who had evacuated from Hiroshima and had no one to take them in. “I didn’t imagine so many of them would gather,” she said. “They chanted sutras together in a fine chorus and held a nice memorial service.” Kimiko is also a survivor of the atomic bombing, losing seven members of her family, including her parents, in the Takara area in downtown Hiroshima.

[Reference] “Human Options” by Norman Cousins

(Originally published on February 26, 1995)