History of Hiroshima: 1945-1995 (Part 7, Article 2)

Aug. 1, 2012

Atomic Bomb Hospitals

by Tetsuya Okahata, Staff Writer

Note: This article was originally published in 1995.

This article will start with a personal experience of the writer: Several years ago, my son developed a high fever and purple spots broke out on his abdomen. The doctor’s suspicion was leukemia. As my wife and I are both second-generation A-bomb survivors, the words “atomic bomb” flashed through my mind. A few days later, a blood test confirmed that leukemia was not the culprit after all. But the cause of the purple spots has remained a mystery.

“To this point, genetic effects involving exposure to radiation have not been observed.” So goes the general thinking of the medical community. However, when a health concern arises, A-bomb survivors and their descendants suspect a link between the atomic bombing and their condition. The bottomless horror of the bombing has been seared too deeply in the A-bombed city of Hiroshima to scoff at this mindset as merely a sentimental argument.

The Chugoku Shimbun will peer into the shadows of radiation fears that have fallen on the hearts of A-bomb survivors and their kin, turning our attention to a boy, a second-generation A-bomb survivor who died of leukemia, and doctors involved in the treatment of A-bomb survivors at the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Hospital.

Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Hospital provides care through survivors’ eyes

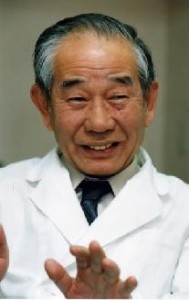

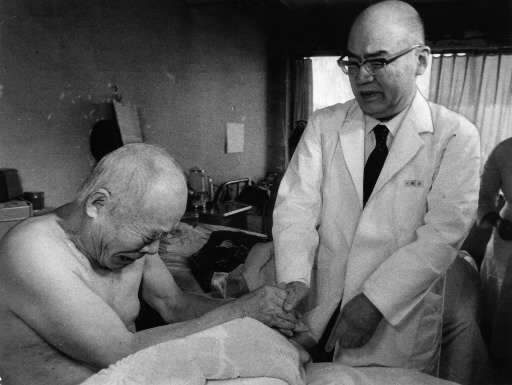

At a nurses’ station inside the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Hospital, Dr. Sadamu Ishida, leafing through medical records, glanced up to find a young woman with a troubled look on her face.

“What disease does he have?” she asked simply. The woman was referring to a 24-year-old man who was now hospitalized after being diagnosed with leukemia, the disease discovered in a round of health checkups for A-bomb survivors. “Are you his sister?” Dr. Ishida replied. The woman shook her head. In line with hospital policy, Dr. Ishida could only share the patient’s diagnosis with the members of his family. Dr. Ishida watched the woman leave, walking away with slumped shoulders. “She’s probably his girlfriend,” he thought. “Poor girl.”

Three months later, at the end of the year, the young man died. A week after his death, the woman attempted suicide by taking sleeping pills. The couple had planned to marry in the spring. “I was shocked,” Dr. Ishida said. “But even if I had told her the name of his disease, it wouldn’t have changed their fate...” The incident occurred 30 years ago, but Dr. Ishida still recalls the experience with regret. The couple’s ill-fated love was later enacted in the film “Ai to Shi no Kiroku,” or “A Record of Love and Death,” which starred Sayuri Yoshinaga and Tetsuya Watari.

These human dramas have been a regular occurrence at the Atomic Bomb Hospital. There was the young mother who let her child wear a kindergarten uniform a day before the child passed away and together they sang “Yuyake Koyake,” a child’s song about the sunset and its afterglow. Over a span of 25 years as a physician treating A-bomb survivors, Dr. Ishida witnessed many such scenes, which honed his mind as a doctor for A-bomb survivors. In all, he has examined and treated survivors on more than 300,000 occasions.

Dr. Ishida came to Hiroshima in 1954, leaving the faculty of medicine at Kyushu University and joining the staff of Hiroshima City Hospital. But in the early days of treating A-bomb survivors, Dr. Ishida disliked the work intensely. He was puzzled by the survivors, who complained of a range of symptoms, including dizziness and paralysis in their hands and legs, as well as symptoms of diagnosed illnesses. When injections were given to them, or incisions were made in their skin, the marks became keloid scars. Once a patient advanced upon him, saying, “Look what you did to my body.”

“It was the irony of fate that brought a man like me to the Atomic Bomb Hospital,” he said. “I guess fate was telling me to learn more about the survivors.” In 1957, Dr. Ishida took up a post at the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Hospital, which had opened the previous year. The director at the time was Fumio Shigeto, who experienced the atomic bombing while serving as deputy director of the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital. Though suffering injuries himself in the blast, Dr. Shigeto did all he could to treat the survivors. As Dr. Shigeto was the authority on medical care for A-bomb survivors, Dr. Ishida’s encounter with him helped shape the rest of his career as a physician.

“He was a great man,” Dr. Ishida said, reflecting on those days. During the director’s hospital rounds, Dr. Ishida noticed something different in the eyes of patients when they saw Dr. Shigeto. Some would even bow their heads and put their hands together in prayer. Dr. Ishida wondered why. Dr. Shigeto was undoubtedly the authority when it came to A-bomb diseases. But was that the only reason? Dr. Ishida would ponder this question as he accompanied Dr. Shigeto on his brisk rounds through the wards.

“Stand on the side of the A-bomb survivors,” Dr. Shigeto always said, Dr. Ishida recalled. He would spare the time to meet with visitors from Japan and overseas, and he spoke out about the plight of the survivors, saying such things as “It’s like A-bomb survivors were pitched inside a nuclear reactor.” Dr. Shigeto’s English was far from perfect, but watching him persistently speak out about the survivors’ plight in his broken words, Dr. Ishida was struck by Dr. Shigeto’s anger. Dr. Ishida came to understand why the eyes of the director’s patients looked at him differently.

Dr. Ishida began his examinations by speaking in depth with his patients. Many A-bomb survivors were suffering from trauma as a result of their horrific experiences of the bombing and their grave fear of developing A-bomb diseases. Dr. Ishida believed that easing their anxieties was the first step in their medical care. The health checkups he performed on a visit to Hokkaido in 1964 reinforced this way of thinking.

During his examinations, Dr. Ishida would first ask the circumstances of a patient’s exposure to the atomic bomb. It was vital to understand these individual circumstances for each A-bomb survivor who was exposed to the massive amount of radiation emitted by the bomb. In Hokkaido, one survivor said to him, “Oh, the Hiroshima dialect. I miss hearing it.” Now living far from Hiroshima, many of these patients in Hokkaido were unable to tell others that they were A-bomb survivors. At the end of their checkups, they would leave with a look of relief on their faces. The thought that he had served as a kind of “tranquilizer” made Dr. Ishida smile.

The following year, 1965, Dr. Ishida returned to Hokkaido to continue offering checkups as a visiting physician. The eyes of these A-bomb survivors, who clasped his hands and asked him to come again, had the same quality as the eyes of the patients he had seen during Dr. Shigeto’s rounds. Dr. Ishida was happy that he could take this step toward the example set by Dr. Shigeto.

Inspired by his experience in Hokkaido, Dr. Ishida began conducting health checkups for A-bomb survivors in eight prefectures, including Aichi and Toyama. He also visited Okinawa before the island chain was returned to Japan. Starting in 1971, he paid visits to South Korea as well.

However, each time he traveled to perform these health checkups, a concern rose in his mind. On every occasion, local government officials would use his visit as an excuse to hide their own lack of support for A-bomb survivors. “We have brought in a medical specialist from Hiroshima,” they would say. But A-bomb survivors in Japan should be able to access adequate treatment no matter where they live. “I’m afraid that my efforts have let governments off the hook and enable them to hide their poor administrative practices involving A-bomb survivors,” Dr. Ishida thought. Following the tenth year of his travels to conduct such examinations, he declined all further requests for checkups, except for survivors in South Korea.

At the end of 1980, Dr. Ishida studied the written opinion issued by the “Conference for Fundamental Problems of Measures for the Victims of the Atomic Bombs,” and thought: “The Japanese government has walked away from the A-bomb survivors.” This written statement stressed the importance of maintaining a balance between A-bomb survivors and other victims of the war when it came to support measures.

And yet... Is the tragedy of a man who dies of leukemia 20 years after the atomic bombing and his girlfriend who attempts to follow him in death the same as that of other war victims? Did another woman who left a heartbreaking diary, in which she begged that her white blood cells not increase in number, end up dying an unavoidable death? Dr. Ishida simmered with rage at the injustice.

Over the next year, Dr. Ishida felt his passion flagging in his role as physician for A-bomb survivors. In the spring of 1982, at the age of 56 and nearly ten years before his retirement, he resigned from the Atomic Bomb Hospital. “Are you fleeing, too, doctor?” a patient asked him, the words painful to hear.

Dr. Ishida took up the post of director at the Ondo National Health Insurance Hospital in the town of Ondo, near his hometown of Kure. At this hospital, too, he was asked to conduct health checkups for A-bomb survivors. He thought: “As long as there are survivors who are suffering, I can’t just sit idly by...” Though he would no longer work with A-bomb survivors as directly and intensely as during his time at the Atomic Bomb Hospital, he was unable to walk away from their care.

Dr. Ishida will turn 70 this year. Four years ago, in the spring, he began working at a clinic in Minami Ward, Hiroshima, where his wife practiced medicine. Once in a while, he visits the Hiroshima Prefectural Health and Welfare Center, among other institutions, to perform health checkups for A-bomb survivors. Even today, the way he examines his patients, beginning with dialogue, remains unchanged. “But for the health checkups at the public health center and at other places, I have to see more than 100 people in a single day. I don’t have the time to listen to their circumstances at the time of the atomic bombing...” Dr. Ishida wore a somber look.

Dr. Ishida plans to visit South Korea this year. Last year, in Hiroshima, he ran into an A-bomb survivor that he had treated in South Korea while working at the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Hospital. The survivor told him, “Doctor, everyone is waiting for you in Korea.” The words were another reminder to Dr. Ishida that the battle of a physician treating A-bomb survivors will continue as long as A-bomb survivors are alive.

[Brief History] Tug-of-war over hospital construction between the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Casualty Council and the Japanese Red Cross Society

In 1954, a Japanese tuna fishing boat, the Daigo Fukuryu Maru, or Lucky Dragon No. 5, was exposed to radiation released by a U.S. hydrogen bomb test conducted at Bikini Atoll. The incident sparked a surge of calls for relief measures to be implemented for A-bomb survivors in Japan. In response to appeals made by survivors seeking a hospital that would specialize in A-bomb diseases, the Japanese Red Cross Society announced a plan the following year to construct Atomic Bomb Hospitals in Hiroshima and Nagasaki with proceeds from the sale of lottery postcards for the New Year’s.

In Hiroshima, the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Casualty Council, a body organized by local governments and medical experts, also envisioned the founding of a treatment facility for A-bomb survivors. A tug-of-war thus ensued between the Japanese Red Cross Society and the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Casualty Council over their competing plans. Hiroo Ohara, the mild-mannered Hiroshima governor, once reportedly banged his fist on a desk and yelled: “Will we build a hospital or not?”

In the end, through the mediation of the Ministry of Health and Welfare, the two sides agreed, among other things, to: 1) construct a hospital on the grounds of the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital as an independent facility, and 2) establish a local steering committee. In September of the following year, 1956, the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Hospital opened its doors with 120 beds. In part because most of the doctors were working for both the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital and the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Hospital, the new hospital was the brunt of such criticism as “Only 18 patients have been hospitalized in the two months since the hospital opened.” In 1967, an annex was added to the hospital and the number of beds increased to 170.

Only two hospitals in the world have “atomic bomb” in their name. Due to their nature, these hospitals have a mission to do all they can in providing medical care for A-bomb survivors and leaving their medical data to posterity. With regard to autopsies, they have performed this procedure at a rate among the highest of hospitals in Japan. However, the hospitals came to suffer financial difficulties as they pursued this mission.

Compounding the problem, as the A-bomb survivors grew older, the rate of turnover for the hospital beds was low. In 1972, the accumulated deficit exceeded 100 million yen. It was not until 1974 that the central government and the governments of Hiroshima Prefecture and the City of Hiroshima began to provide the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Hospital with subsidies earmarked for the purchase of medical equipment, among other needs.

For all these reasons, the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Hospital merged with the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital in 1988. The name of the hospital was changed to the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital & Atomic Bomb Survivors Hospital, and the finances of the two institutions were consolidated as well.

(Originally published on March 5, 1995)