History of Hiroshima: 1945-1995 (Part 15, Article 2)

Aug. 1, 2012

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

by Tetsuya Okahata, Staff Writer

Note: This article was originally published in 1995.

Five years before Olof Palme, the former Swedish prime minister, was assassinated in 1986, he paid a visit to the city of Hiroshima and saw the “Human Shadow Etched in Stone,” one of the exhibits on the atomic bombing found in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. Sharing his impression, Mr. Palme said that if a nuclear war were to take place, there would be nothing left but human shadows--then changed his mind and declared that even our shadows would vanish from the earth.

Even 50 years after the bombing, A-bomb artifacts, conveyors of the horror of that day, possess the power to deeply shake those who gaze upon them. A lunch box charred black. A singed and tattered school uniform. About 1.4 million people visit Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum each year and listen to the silent cries of these artifacts, searing the horror of nuclear war into their minds and moving them to share the grief of the atomic bombing with the citizens of Hiroshima and other visitors.

The people of Hiroshima have long been gathering and displaying A-bomb artifacts, as far back as the aftermath of the bombing. In order for humankind to survive, they see it as their duty, as those who experienced the horror of the world’s first nuclear attack, to leave behind channels to convey the reality of this catastrophe. However, as the scuffle over an exhibition on the atomic bombing at the Smithsonian Institute makes clear, a large number of people still contend that displays of this kind exaggerate the damage wrought by the bomb.

With personal memories of the A-bomb experience fading, the A-bomb artifacts have assumed an even weightier significance. The Chugoku Shimbun explores the emotions tied to such artifacts of the blast, centering on the stories of Kyoto University students who held the first full-scale A-bomb exhibition, despite the ongoing U.S. occupation, and a woman who donated her hair--hair which fell out due to the aftereffects of the bombing--to Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, now marking the 40-year anniversary of its opening.

Hair, lost to bomb’s radiation, is donated to museum

You asked me to show you a wedding photo.

Yes, the time has come to tell you the story.

Back then, your mother was young,

eighteen years old and proud of her long, braided hair.

It was a quiet morning, as I recall.

Then time seemed to stop at 8:15 a.m.

[...]

When I first met your father, I was completely bald.

The radiation from the atomic bomb had invaded my body,

and every strand of my black hair, the symbol of a young girl’s life,

fell out, leaving no trace at all.

I cried alone, continuously,

but your father loved me just the same.

He said he didn’t care that I was bald.

Now you know why we have no wedding photos.

But even though I have no photos, I don’t feel sad at all.

Because now I have your father, and I have you.

Hiroko Yamashita, 68, a resident of Higashi Ward, Hiroshima, crafted this poem 22 years ago. The poem, called “Mother’s Wedding Photo,” was written in response to her son, who once wondered why, unlike other families, there were no wedding photos of the parents in their house.

“When he was in kindergarten, it seems he saw a wedding photo at a friend’s house,” explained Ms. Yamashita. “The incident lingered in my mind for a long time. Years later, when a TV station was seeking poems on the theme of a wedding dress, this is the poem I wrote.” She gazed at a photo of her eldest son, dressed in a swallow-tailed coat, that was displayed on a shelf.

At the moment she was exposed to the flash of the atomic bomb, she was overwhelmed by a sudden feeling of dread, as if sinking into a deep pit of darkness. That day Ms. Yamashita was at home in the Otemachi district, about 800 meters from the hypocenter. She experienced an enormous blast and became trapped under the wreckage of the house. Unable to move, she thought she would die, and she hoped to die a humble death as “a girl with a military spirit.” Placing her hands together in prayer, her mind flashed on the faces of her parents and siblings. Suddenly she remembered that her younger brother, a first grader, was at home, too.

“I have to save my brother,” she thought. She struggled desperately to free herself from the wreckage and finally managed to squirm out. She could see the hazy light of the sun shrouded behind a pitch-dark sky. Looking around, she spotted her brother crawling on the ground. With flames approaching, Ms. Yamashita put her younger brother on her back and fled with all her might.

The moment she arrived at an airfield in Yoshijima, she collapsed to the ground. Her body had been riddled with 37 different wounds. There were countless numbers of injured people around them. One mother held fast to her dead baby. Ms. Yamashita was up the whole night, staring at the reddened sky as it reflected the fire from the ground.

A week later she was reunited with her parents and the family took refuge in the house of a relative in the former village of Kakogawa, located in Hiroshima Prefecture. But Ms. Yamashita was unable to sit up. Her younger brother, who had escaped with only mild injuries, abruptly came down with a high fever on August 21. When Ms. Yamashita looked at her brother, sleeping next to her, she discovered several short lengths of hair by his pillow, as if a cat was shedding. When her mother touched the boy’s head, all his hair fell out.

Word had swirled that hair loss was a sign of impending death. Ms. Yamashita summoned the courage to ask her mother to comb her own hair. When her mother ran a comb across her scalp, her hair came out in a clump. Her brother had a continuous nosebleed for the next two days and nights, then died clutching his mother’s breast and uttering a goodbye. Steeling herself for her own demise, Ms. Yamashita caressed her brother’s face, which was starting to grow stiff.

Ms. Yamashita managed to escape death, but troubled by A-bomb illness, she moved into her older sister’s house in the Kusatsu area so she could undergo treatment at a hospital nearby. Her hair had not grown back yet, and she wore a scarf around her head. The stares of other people pained her, while sadness welled in her heart when they looked away.

While facing this difficult time, Ms. Yamashita received a proposal of marriage from a man named Hirozo Yamashita. Now 68, Mr. Yamashita was a bank employee who was lodging at her sister’s house. Ms. Yamashita, though, was at a loss, unsure when she would be struck again by illness. Around that time, she heard that a shelter for A-bomb orphans had opened in the nearby city of Itsukaichi. As if fleeing from Hirozo and his proposal, she took up a live-in position at the shelter and began working there. But it was demanding, round-the-clock labor, not the sort of job that someone with fragile health could endure.

Two years after the atomic bombing, Ms. Yamashita accepted Hirozo’s proposal. Later, Hirozo revealed to his wife: “I was hoping you would live for at least five years.” This was because Ms. Yamashita had become so frail. The idea of bearing a child seemed merely a dream.

Still, in the 15th year of their marriage, Hiroko conceived the baby she had long dreamed of having. Hirozo and her parents, however, were opposed to her carrying the baby to term. Her mother even told her, “If you die soon after the baby is born, what will become of Hirozo and the baby?” But Ms. Yamashita, who wanted to repay her husband for the love he had given her, did not waver in her will to bear the child. Overcoming a difficult delivery, she gave birth to a baby boy. Though the infant was premature, weighing just 1,400 grams, his remarkable growth surprised their doctor.

Today, her son is a young, promising conductor and active on the world stage. At times, her son and her lost brother commingle in her mind. Her younger brother enjoyed music, too, and the pure-hearted boy would shed tears when he heard a sad-sounding piece.

Ms. Yamashita, who was encouraged by her husband’s love and raised a healthy child, has nevertheless been unable to pull away from the fate of her exposure to the atomic bomb. While her hair gradually grew back, her life has been a revolving door of hospital visits and she has undergone three operations for thyroid cancer. Each time she has a parting with her son, she holds his hands firmly as she thinks, “This may be the last moment I see him.”

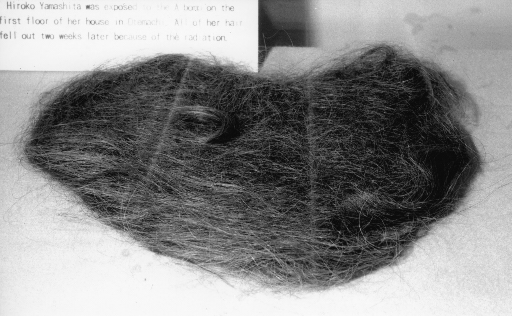

The hair she lost has been put on display in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. With the possibility that she might have died at any moment, her mother kept the hair in a drawer of the Buddhist altar at their home. The hair was donated to the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Hospital in 1957, and some of it was then given to the museum the following year.

The black hair, still crusted with dust that flew in the city on that day, and turning a brownish color in its acrylic case, continues to convey a “poem” of the A-bombed city to museum visitors.

First director of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum devoted his life to collecting A-bomb artifacts

It was the passion of a geologist that helped bring Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum into being. Shogo Nagaoka was the first director of the museum and he devoted his life to gathering artifacts of the atomic bombing under a philosophy of “faithfully conveying to future generations the scars made on human history by the devil.”

Mr. Nagaoka was a part-time staff member of the Department of Geology and Mineralogy at the Hiroshima University of Literature and Science (now, Hiroshima University). The day after the atomic bombing, he entered Hiroshima to find out whether the university and his relatives were safe. He managed to reach Gokoku Shrine and sat down on a stone lantern. But he quickly jumped to his feet after feeling a needle-like pain.

The surface of the stone was shiny, with numerous sharp projections, and these spines were angled in a certain direction. Mr. Nagaoka assumed these projections rose up from the stone when the surface was melted by the blast of intense, instantaneous heat from the atomic bomb. “Something unusual has happened,” his intuition told him. “This must be the effect of the bomb I heard about at the university.”

From that day, he began wandering through the burnt ruins of the city with a backpack on his shoulders. He examined the different directions and angles of the heat rays from the “shadows” left on granite gravestones and gateposts and calculated their calorific value by taking into account the distance and direction from charred roof tiles and stones. He would sell books on geology at the black market, fill his empty bag with A-bombed roof tiles and stones, then return home.

“One of the rooms in our house was taken over with his junk,” said Mr. Nagaoka’s eldest son Seiichi, 71, a resident of Otake City, Hiroshima Prefecture. “It was like the storage room of a museum.” Meanwhile, the horror of the bomb’s residual radiation was spreading among the public. For a week in early September, Mr. Nagaoka developed a high fever and diarrhea. His wife Harue insisted that they take the A-bomb artifacts outside, asking, “Which is more important, your life or these things?” Mr. Nagaoka replied: “The roof tiles, of course.”

Later, too, Mr. Nagaoka revealed his honest emotion: “Out of the 20 photos I took in the aftermath of the atomic bombing, 16 of them were exposed to radiation. It made me feel a bit uneasy.”

A-bomb artifacts that were gathered in this way played a large part in identifying the location of the hypocenter.

As the reconstruction of the city went on, the Hiroshima city government realized the significance of the A-bomb artifacts. In 1949, the city established a room to exhibit such artifacts at the Chuo Community Hall in the Motomachi district. Government officials asked Mr. Nagaoka to contribute about 6,700 artifacts, and issued a letter appointing him to serve as part-time administrator of the room. When Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum was completed in 1955, Mr. Nagaoka became its first director.

The director of the museum is a high-profile face of the A-bombed city of Hiroshima. During Mr. Nagaoka’s tenure as director, he spoke to well-known international figures about the horrific consequences of the bombing, including Jawaharlal Nehru, the Indian prime minister, and Eleanor Roosevelt, the former first lady. Mr. Nehru reportedly shook Mr. Nagaoka’s hand and said that, thanks to him, the A-bombed city of Hiroshima would always be in his thoughts.

Even after retiring from the post of director in 1962, Mr. Nagaoka continued to collect and analyze A-bomb artifacts. He opposed putting wax figures in the museum to show the misery of the A-bomb survivors, an issue which stoked controversy, saying, “No matter how realistic they appear, they’ll still be fake.” The wax figures appeared six months after Mr. Nagaoka died in 1973 at the age of 71.

“My father led the life of a student throughout his lifetime,” Seiichi said. “He felt that only the real artifacts would have the power to appeal for peace. The more the memory of the A-bombed city faded from people’s minds, the more strongly he felt that way. As a result, his thinking was at odds with the city’s policy.” Mr. Nagaoka was always a part-time employee of the city, right up to his retirement.

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum is imbued with the tenacity of the late geologist. However, his name does not appear in the museum brochure nor in its exhibitions rooms, which fill each year with a stream of more than one million visitors.

Article in the Chugoku Shimbun on August 18, 1960

Hiroshima mayor’s vision: Transform peace museum into art museum

In August of 1960, Hiroshima Mayor Shinso Hamai spoke at a news conference and announced a plan to transform Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum into an art museum. His reasoning was that the museum was a source of pain to A-bomb survivors and the bereaved families of A-bomb victims.

According to the Chugoku Shimbun of August 18, 1960, Mr. Hamai stated: “The original purpose of a park is to serve as a place of relaxation for the public. But we regularly hear voices, and receive messages, which say that the A-bomb artifacts found in the museum are reminders of family members who died in misery and this pains the hearts of survivors and makes them unable to go near the park. In a vacant area south of the Atomic Bomb Dome, we would like to build a new museum to remember the atomic bombing while converting the current museum into an art museum, as many have wished.”

The article went on to say that author Robert Jungk, while on a visit to Hiroshima, personally expressed his objection to the mayor’s vision, arguing that art museums existed all over the world but Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum could only be found in the A-bombed city of Hiroshima, and that the tragedy of that day must not be upstaged by other concerns.

(Originally published on April 30, 1995)