History of Hiroshima: 1945-1995 (Part 17, Article 1)

Mar. 7, 2013

Dawn of the Peace Movement I

by Yoshifumi Fukushima, Staff Writer

Note: This article was originally published in 1995.

In the decade following the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, memories of the catastrophe were still fresh in people’s minds. For two-thirds of this period, Japan was under U.S.-led occupation. As a result of the oppression engendered by the occupation, with its deft decrees, the peace movement in Japan arose, led mainly by labor organizations. It was a time of bitter struggle, hardly the dawn of a peace movement. Still, even in those early days, voices in the A-bombed city of Hiroshima did more than utter wishes and prayers, they spoke out against the atomic bombing. This history, which served as a prologue for the subsequent campaigns against A- and H-bombs, should not be forgotten.

Meanwhile, since the end of the war, scientists concerned about the fate of the human race following the advent of atomic and hydrogen bombs, borne of science itself, have sustained their own effort to call into question the context of nuclear power and warfare.

In those early days, the peace movement was heavily tinged with contrition and remorse over the war and the misuse of science as well as a sense of human conscience and an uncontrollable fury against atomic bombs.

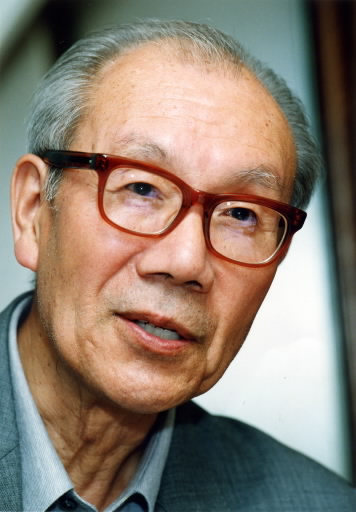

Kiyoshi Matsue, leader of “Hiroshima Rally to Preserve Peace,” appeals for abolition of atomic bombs

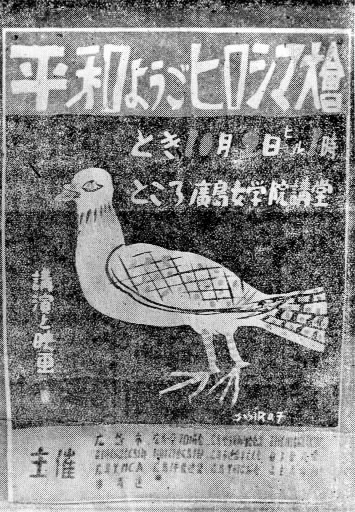

Declarations drafted by gatherings of like-minded people often conclude with a sentence that starts: “We declare that...” However, in the statement issued by the “Hiroshima Rally to Preserve Peace” this sentence is followed by another sentence consisting of 45 Japanese characters.

This additional sentence, when translated, reads: “Hiroshima citizens, as the first victims of atomic bombing in the human history, demand that ‘all atomic bombs be abolished.’”

The declaration by the Hiroshima Rally to Preserve Peace was made in the auditorium of Hiroshima Jogakuin Junior High School on October 2, 1949, at a time Japan was still under the occupation of the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ). The brief, additional sentence is the very first appeal issued from the A-bombed city of Hiroshima for the abolition of nuclear weapons.

Following the rally, the next day’s edition of the Chugoku Shimbun carried an article about the event that ran just 12 lines. The newspaper will now explore that era, only hinted at in the article.

Kiyoshi Matsue, 75, then president of the Hiroshima Prefectural Trade Council and now a resident of Naka Ward, Hiroshima, was intently scanning the venue for the Hiroshima Rally to Preserve Peace from his chair. He was first relieved to see that no occupying forces or police officers were present at the venue, something that had worried him. The rally was the first full-fledged peace and anti-war gathering organized by a private organization.

“During our preparations for the rally, I had been summoned by the GHQ intelligence section in Yoshiura,” recalled Mr. Matsue, who was under indictment in a labor dispute. The rally would form part of the “International Day of Struggles for Peace,” initiated by the World Federation of Trade Unions. The Hiroshima Prefectural Trade Council proposed holding the gathering and made the first move. In those days, the labor movement was seeking to open up the closed era, including in the area of peace and anti-war activities.

At the GHQ office, the man overseeing such public gatherings asked Mr. Matsue what sort of event it would be. “It’s a peace gathering,” Mr. Matsue replied. “It’s a democratic meeting to oppose fascism, like the fascism espoused in Japan before the war.” The man, though, showed an apprehensive look, concerned that the gathering would involve communism or a radical anti-war or A-bomb-related agenda.

The GHQ was particularly sensitive on the subject of the atomic bombs. It sought to justify the legitimacy of the A-bomb attacks, and their catastrophic consequences, by contending that the bombings ended the war and brought about peace. Criticism of the bombings would be troublesome to the occupying forces.

In the year before the Korean War broke out, reconstruction efforts in the A-bombed city of Hiroshima began in earnest, in line with the Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Law, while the Cold War between East and West escalated with the Soviet Union now in possession of its own atomic bomb. In addition, following the founding of the People’s Republic of China, a communist state, Japan’s labor movement faced more severe suppression from the authorities. Communist China was born just a day before the Hiroshima Rally to Preserve Peace was launched.

Against this backdrop, expressions like “anti-war” and “atomic bombing” were intentionally avoided in the slogans used at the venue for the rally. Women’s organizations and people from academia essentially toed the line in expressing sentiments fit for public consumption in their statements, as opposed to their true feelings, including their support of “democratic rights,” in order to prevent an adverse response from the occupying forces. Amid the stilted arguments made at the venue, one woman rose to her feet and broke the mood.

Before she knew it, Kinko Yamada, now 72, a resident of Nishi Ward, Hiroshima, was standing and speaking to the crowd. “If there were no atomic bombs, people wouldn’t be in the position of using them,” she said. “We shouldn’t allow more bombs to be made.” Ms. Yamada, who was attending the event merely at the urging of a union, was enveloped in applause.

Her husband, who was sent to the battlefields of Southeast Asia just a week after they were married, was a casualty of the war. In the aftermath of the atomic bombing, Ms. Yamada entered the city and was exposed to the bomb’s residual radiation. The post-war era found her, along with her mother and two younger sisters, who had experienced the bombing directly, struggling valiantly to survive. Ms. Yamada’s remarks at the rally were kindled by her frustration in the fact that no clear objections to the atomic bombing were being made, though it had seemed they would soon appear.

“I hate atomic bombs and war, which bring suffering to ordinary people,” she said. “I didn’t prepare what I said in advance; it was something I felt from the heart.” At that point, four years had passed since the atomic bombing. People lived in fear of the occupation by foreign troops. However, contrary to the aims of the occupying forces, A-bomb survivors loathed the attacks.

Mr. Matsue, the former Trade Council president, said, “The truth is, I hoped to pass some kind of resolution on the atomic bombing one way or another.” However, the declaration issued at the rally, which had been shown to the GHQ in advance, did not contain language calling for a ban on atomic bombs. If the GHQ had known that the rally’s real intent was to express opposition to these weapons, the event would have been cancelled. Though the declaration was read out loud, with Ms. Yamada’s remarks hastily added, the GHQ did not respond with a reprimand.

Standing in the ruins of the city after the atomic bombing, Mr. Matsue made a vow to oppose war. This was the starting point of his struggle. Earlier, when he was a student at the University of Tokyo, Japan experienced a precipitous rise in militarism. As a sophomore, he was drafted into the military and dispatched to the front lines in Manchuria, the northeastern part of China. He was then brought back to Japan and added to an education corps. Meanwhile, some fellow students of his were killed when the Soviet Union joined the fighting, while others were detained in Siberian labor camps. Mr. Matsue said he finds it hard to assuage his “deep-seated remorse” over quietly following the militaristic thinking of that time.

Then the atomic bomb was dropped. Mr. Matsue saw the burnt ruins of the city around August 20, after he was discharged from the military and returned to Hiroshima. When he went to the Kamiyanagi district, where his parents’ house had stood, he could find no trace of it at all. He learned that his older brother, a doctor, had been killed instantly in the blast, though he was unable to discover where he had died. His mother passed away, too, three years after the bombing. Yet Mr. Matsue resolved to remain in the A-bombed city.

Mr. Matsue later wrote a memoir which included these words: “My participation in the anti-war movement is directly motivated by my bitterness over the war and the atomic bombing, which destroyed my hometown and stole away my mother and my older brother. The bitterness I feel is evidence that I’m still alive yet also a barrier in my mind which prevents me from helping to create a new society.”

As if timed to suppress the passion Mr. Matsue was feeling, a shadow fell over Japan in the year that followed the Hiroshima Rally to Preserve Peace. With the outbreak of the Korean War, oppression by the GHQ reached its peak. In August, the Hiroshima City Police joined the crackdown by banning all peace-related gatherings. Defying this ban, Mr. Matsue and others went ahead and planned illegal gatherings for August 6. These events would now bring together only activists. “Even so, I couldn’t stand the situation, where we couldn’t even speak out against war and atomic bombs,” Mr. Matsue said.

On the day of the gathering, the group of activists avoided the eyes of police officers on alert and scattered leaflets from the roof of the Fukuya Department Store in the Hacchobori district. While passersby were picking up the leaflets and reading them, about 150 activists who had disappeared into the crowd came together quickly and chanted a protest--then dispersed a moment later. An “instant gathering” like this was held in front of the main train station, too. Mr. Matsue, though, remained behind in a hideout and a messenger came to relay news about these actions.

The text of the leaflet demanded “End the Korean War now!” and, in smaller type, “Abolish atomic bombs!”

In his book of poems entitled “Genbaku Shishu” (“Poems of the Atomic Bomb”), poet Sankichi Toge included the poem “1950 Nen no Hachigatsu Muika,” or “August 6, 1950,” which depicted these “guerrilla” gatherings. Mr. Toge was one of the leaders of the Hiroshima Rally to Preserve Peace and he had forged deep ties with Mr. Matsue through the post-war pro-democracy movement. “I don’t think Mr. Toge was actually at the scene that day, so I guess he heard about it secondhand,” Mr. Matsue explained. “He wrote the poem with our efforts that day firmly in mind. It was his way of expressing opposition to war.”

Although “Abolish atomic bombs!” was a secondary demand of the leaflet, these words were imbued with the conviction that the sort of bomb dropped on Hiroshima must not be used again in the Korean War. “That was why the gatherings had to be held, even if they were illegal,” Mr. Matsue said. About three months later, U.S. President Harry S. Truman stated that he was considering the use of an atomic bomb in Korea.

In the summer of 1952, when the peace treaty between Japan and the United States went into force and the occupation came to an end, a mass gathering to promote peace was staged in front of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, which was then under construction, by such entities as the Hiroshima branch of the Japanese Trade Union Confederation, cultural organizations, and peace groups. The declaration issued at the gathering called clearly for a ban on the production and use of atomic weapons. Mr. Matsue, who was involved in this meeting as president of the Hiroshima Prefectural Trade Council, looked back on those days and said, “The gathering was still under police surveillance, but no one complained any longer about our appeal to ban atomic bombs.” It had been two years since Mr. Matsue, then the head of the Chugoku Shimbun’s labor union, was fired due to Japan’s “red purge,” a nationwide sacking of suspected communist “subversives.”

Mr. Matsue served five terms, or a total of 20 years, as a member of the Hiroshima prefectural assembly and was an executive member of the Hiroshima Congress Against A- and H-bombs as well. Afterwards, too, he has continued to be active in the anti-war and anti-nuclear movement. Mr. Matsue has been organizing a gathering of citizens every August for the past ten years. While the energy of the citizens’ movement has waned, he continues to question the issues of war and nuclear weapons, as well as nuclear energy, which he finds inextricably linked.

Forty-six years have passed since the Hiroshima Rally to Preserve Peace issued the first appeal for a ban on atomic bombs. Shinso Hamai, who was mayor of Hiroshima at the time and had been approached by Mr. Matsue for his cooperation in holding the rally, contacted him just prior to the event with this message: “The occupying forces told me that it isn’t a good idea for the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Service Committee to take part in the gathering.” Having attended the same high school and university, Mr. Hamai and Mr. Matsue knew each other well. Yet Mr. Hamai, the A-bomb mayor, refrained from using the expression “a ban on atomic bombs” in the telegram that he sent to the gathering.

Mr. Matsue assessed the era in which his passion burned while enduring hardship: “The A-bomb experience, a sort of national experience, wasn’t simply hidden and suppressed by the occupying forces. That experience was also locked away deep in the hearts of many people. For the experience of the A-bombed city of Hiroshima to be revived, and the public’s outrage over the experience to erupt, we had to wait for the Bikini Incident to occur.” [The Bikini Incident involved a Japanese fishing boat suffering exposure to radioactive fallout from a U.S. hydrogen bomb test in the Pacific Ocean in 1954.]

“Hiroshima group” of the Japan P.E.N. Club vows to make efforts for peace

On April 15, 1950, when Japan was still under the occupation of the Allied Powers, a gathering of writers from the Japan P.E.N. Club’s “Hiroshima group” was convened at a gas company building in the city. At this “Hiroshima Group,” which was one of the epoch-making peace efforts of the post-war era, the writers issued a declaration that was imbued with their determination and passion to seek peace. As men of letters, they vowed to exert their best efforts, without limit, to promote world peace and proclaimed this resolve to those at home and abroad.

Nineteen standard-bearers of the literary world, including Yasunari Kawabata, Tatsuzo Ishikawa, and A-bomb writer Tamiki Hara, had converged in Hiroshima for their first conference in the A-bombed city. They also held lectures from a line-up of writers, taking the podium one after the other, as well as a round-table meeting with A-bomb survivors, hosted by a magazine company. The lectures, which ran two hours longer than scheduled, was a great success.

Yoichi Goto, 81, a professor emeritus at Hiroshima University and a resident of Saeki Ward, was one of the A-bomb survivors who shared his A-bomb experience at the round-table meeting. “I sensed that the literary world had a strong desire to learn about the atomic bombing,” he said. “It was a signficant gathering in that, as writers of the A-bombed nation, they confirmed that the pursuit of ‘absolute peace’ was an inescapable challenge for them.”

Masafumi Nakai, 82, a resident of Hatsukaichi City and also a professor emeritus at Hiroshima University, was invited to the conference by his friend Mr. Ishikawa, the writer. Mr. Nakai joined the round-table meeting as well, and recalled: “Though the cruelty of the atomic bombing was emphasized, no criticism was made of atomic bombs themselves. With Japan still under occupation, it must have taken a lot of courage and effort just to hold the conference.”

In the year leading up to the conference, Mr. Kawabata, the president of the Japan P.E.N. Club at the time, came to Hiroshima with his colleagues at the invitation of the City of Hiroshima. After the group returned to Tokyo, the executive members of the organization made an urgent motion at their next meeting: “The Japanese have nearly forgotten about the tragedy in Hiroshima. Hiroshima’s voice is the very warning that can preserve peace in the world. Let us go to Hiroshima.” The passionate proposal came four years after the atomic bombing.

Today, the Japan P.E.N. Club has about 1,700 members. Man Arai, 48, a resident of Yokohama, is the head of the group’s peace committee and a winner of the Akutagawa Award. “The declaration is infused with the genuine feeling of the writers who learned firsthard about the devastation wrought by the atomic bomb,” he said.

During a visit to Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, Mr. Arai was once shocked to discover that his hometown of Niigata had also been a target of an atomic bomb. When he calculated the date he was conceived, the result was August 15, 1945. If the war had lingered much longer, he might never have lived at all. Mr. Arai even wrote a novel on this theme, entitled “Ayaui Inochi” (“Life at Stake”).

This past March, the year marking the 50th anniversary of the atomic bombing, Mr. Arai organized a gathering in Hiroshima called “The Day of Peace.” The writers, young and old, spoke about war and peace at the event designed to ponder “the preciousness of life,” which serves as the foundation for peace. From each personal perspective, the writers are now creating work on this theme. The seeds of this effort were planted 45 years ago with the “Hiroshima group.” “The ‘Day of Peace’ is a modern version of the ‘Hiroshima group,’” Mr. Arai said.

(Originally published on May 14, 1995)