History of Hiroshima: 1945-1995 (Part 19, Article 1)

Mar. 10, 2013

Split in the Campaign Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs I

by Tetsuya Okahata, Staff Writer

Note: This article was originally published in 1995.

The campaign against atomic and hydrogen bombs, which developed into Japan’s largest mass movement, eventually suffered a shift in its nature when political parties intervened. The Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs, the pillar of the campaign, fractured in two, with the forces of the Socialist Party and the General Council of Trade Unions (Sohyo) in Japan on one side and Communist Party supporters on the other. Many citizens and A-bomb survivors then distanced themselves from the movement.

Japan’s campaign against atomic and hydrogen bombs no doubt had a huge impact on the worldwide peace movement and helped propel nuclear disarmament efforts. At the same time, its leaders are accountable for the disastrous tug-of-war they waged, which cast aside citizens and A-bomb survivors and brought gridlock to the campaign.

The Chugoku Shimbun examines twin images of the campaign against atomic and hydrogen bombs--one genuine, one false--through the lens of the ninth meeting of the World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs in 1963, when the split became a fait accompli, as well as the lives of two activists who were involved in the campaign for many years.

Night of the split marked by exhaustion and despair

“The pale twilight that precedes moonrise silhouettes like dark waves the participants who have completely filled the Peace Park lawn. They include representatives from districts throughout Japan. The mood is tense.”

This is how the author Kenzaburo Oe began his description of that night in his book “Hiroshima Noto” (“Hiroshima Notes”).

In front of those “dark waves” filling Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, about 60 students from the All-Japan Federation of Students’ Self-Governing Associations occupied the space in front of the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims. “Close the conference immediately if it can’t even oppose nuclear tests,” said the students. “Go home, students,” responded the conference participants. Shouts of anger swirled in the air. Before long, police officers carried the students away. The crowd of citizens fell silent outside the roped-off area and stared intently at the scene.

Thus, on August 5, 1963, the curtain came up on the ninth meeting of the World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs, the conference boycotted by the Socialist Party and the General Council of Trade Unions. It was the night the campaign against atomic and hydrogen bombs became split in two, forsaking the wishes of the A-bombed city of Hiroshima and, as a result of this overt political tug-of-war, paralyzing public opinion on anti-nuclear issues for many years to come.

“Even now, I feel sorry when it comes to the citizens of Hiroshima. We had neither the wisdom nor the courage to repel the forces of the political parties.”

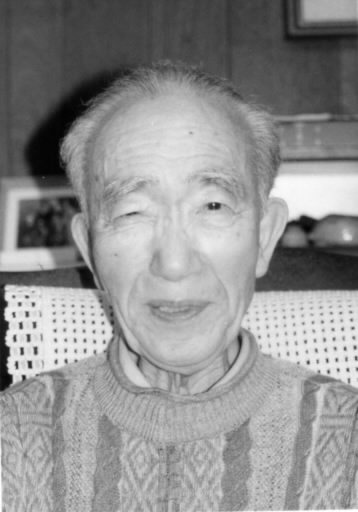

Mitsuru Ito, 84, a former professor at Hiroshima University, reflected on the bitterness of 32 years ago from his home in Tokyo. At the time Mr. Ito was the secretary general of the Hiroshima Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs. Along with the late director Ichiro Moritaki, he was in charge of organizing the conference. “We were intent on not killing the light of the conference against atomic and hydrogen bombs. I thought that problems over political differences could be resolved only if we held the conference in Hiroshima... It was an overly optimistic outlook.”

The first World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs was held in 1955, after the campaign opposing these weapons gained momentum as a national movement in the wake of the Bikini Incident in 1954. As the graphic facts of the atomic bombing were disclosed for the first time, people were shocked and in tears. Their deep distress and indignation was channeled into a vow: “No More Hiroshimas.”

Just eight years later, there was bedlam in front of the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims as people clashed in hatred. What happened to effect this change in the nature of the campaign against atomic and hydrogen bombs, which had begun as a true national movement, beyond ideology? The ironic twist of history is that this shift was triggered by issues involving the revision of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty in 1960, when the public’s political awareness reached its peak in the postwar period.

That year, at the sixth meeting of the World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs, ideology rose to the surface and the expression “American imperialism” appeared in its declaration. The Liberal Democratic Party was the first to react sharply to this development. Then, in 1961, the members of the Socialist Party left the Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs and established the National Council for Peace and Against Nuclear Weapons.

With politics casting a growing pall over the movement, the differences in outlook between the supporters of the Communist Party and the Socialist Party, both of which had exerted a strong influence on the policies of the Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs, began to smolder within the organization. The conflict then came to a head in September of 1961 when the Soviet Union resumed its nuclear testing program. While the Socialist Party had adopted the position of “opposing nuclear tests by any nation” as a principle of its campaign, the Communist Party took a different stance, based on its anti-American and anti-imperialist orientation: “Nuclear tests conducted by a socialist nation in self-defense cannot be put in the same category as nuclear tests performed by an imperialist nation.” As a result of the schism between the two groups over this issue, the eighth meeting of the World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs, held in 1962, was thrown into chaos and the functions of the Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs were suspended.

At a gathering of the leadership of the Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs, which took place in Tokyo on May 24, 1963, Mr. Moritaki, director of the Hiroshima chapter of the organization, couldn’t keep from raising his voice in reaction to the others’ indecisiveness over holding the ninth meeting of the World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs. “We will do it because we must,” Mr. Moritaki said.

In 1963, the discord between the Socialist Party and the Communist Party escalated sharply. On March 1, the ninth anniversary of the Bikini Incident, the Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs was pitched into a state of disarray when the executives of the organization resigned en masse, including the group’s first director, Kaoru Yasui. The opening of the ninth meeting of the World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs was now at stake. The Hiroshima Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs, feeling a heightened sense of crisis, sought to revive the campaign through solidarity with other local councils, independently of moves made by their peers in Tokyo. The Yamaguchi Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs served as an ally.

“In Yamaguchi Prefecture, the Socialist Party and the Communist Party weren’t on bad terms,” recalled Kazunari Abe, now 68, president of the University of East Asia. At the time he was the director of the Yamaguchi Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs. “In Hiroshima, too, there was no friction among academics. I thought we could stand together with Hiroshima taking the lead.”

The alliance of local chapters moved forward without Tokyo. The Hiroshima council called for the representatives of the organization’s local chapters to gather in Hiroshima, where they agreed to take the necessary steps to hold the conference, even if that meant relying only on themselves to do it. It was this determination that Mr. Moritaki was expressing at the May meeting in Tokyo.

However, the political players who viewed the movement as a means of expanding their organizations would pay no heed to the pure will of the local chapters. Ryoichi Yasutsune, director of the political division of the General Council of Trade Unions, went so far as to say: “It’s arrogant to assume that local action can move Tokyo. An order from us and the prefectural branches of the organization, the main actors of the local councils, can be withdrawn.”

But if the Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs could not hold a conference, it would have no reason to exist. After a number of twists and turns, a gathering of the General Council of Trade Unions, the Socialist Party, and the Communist Party produced an agreement to rebuild and bring unity to the organization. At a meeting of the board of directors, held on June 21, the decision was made to hold the ninth meeting of the World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs. That night Mr. Moritaki drank a toast to the outcome, saying, “The passion of the local areas moved Tokyo to act.” The ring of the toast, however, was little more than a prelude to the group’s split.

“Even the regular members of the board of directors of the Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs are all at their wits’ end. They slump down on benches, sighing and grumbling ‘any country...’ as if it were a greeting.” (“Hiroshima Noto.”)

On August 4, a heavy air hung over Hiroshima Peace Memorial Hall with little headway being made on the final preparations for the next day’s opening of the ninth meeting of the World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs. Thanks to the resolve shown by the local chapters, the Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs had moved forward with the event, but during the process of preparing the conference, the controversy over nuclear testing flared again. And the new point of contention became the Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water, which was initialed [not officially signed, but temporarily initialed] at the end of July by the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union.

The Socialist Party expressed their support for the treaty, seeing it as a result of the campaign against atomic and hydrogen bombs. But the Communist Party took a stand that was similar to China, contending that, without the inclusion of nuclear testing underground, the treaty only offered the illusion of a ban. This division took place against the backdrop of rising tension between China and the Soviet Union. Despite calls for moderation from Hiroshima Mayor Shinso Hamai and academic figures, their voices did not cut through the war of words.

Even as night fell, the impasse remained. Makoto Kitanishi, now 69, a professor at Hiroshima Shudo University who was then deputy secretary general of the Hiroshima Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs, waited for Mitsuru Ito, the secretary general, to return to the nearby Hiroshima Peace Hall. The members of the board of directors all looked exhausted. When Mr. Ito appeared, he had a deeply-troubled look on his face. He said that the decision was made to give the Hiroshima Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs carte blanche to run the conference.

Mr. Kitanishi recalled: “The supporters of the Socialist Party advanced the idea of giving us free rein to run the conference. Maybe they were thinking, in light of the makeup of the board of directors of the Hiroshima chapter, that everything would work out in their favor if the task was simply left to Hiroshima.” But these hopes quickly went awry. A fierce battle to mobilize supporters developed, and showed, in the end, the overwhelming advantage of the Communist Party. Fearing that the Communist Party would wrest control of the conference proceedings, the forces of the Socialist Party and the General Council of Trade Unions proposed holding a one-day gathering without separate meetings on other days. But Mr. Ito and others rejected the idea. In the end, just prior to the opening of the conference on the evening of August 5, the supporters of the Socialist Party and the General Council of Trade Unions decided not to participate in the conference.

While Mr. Abe was waiting in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park for the conference to start, a representative from the Yamaguchi prefectural branch of the General Council of Trade Unions approached him. The man said, “I cannot take part in the conference. But please treasure the spirit carried under the banner of the Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs.” Right after that, the students occupied the space in front of the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims. Members of the Hiroshima prefectural branch of the General Council of Trade Unions, who were in charge of security around the venue, had already disappeared.

Mr. Moritaki then delivered a lonely keynote speech. It was described this way in “Hiroshima Noto”:

“As he addresses the conference in front of the Memorial Cenotaph, another and quite different activity takes place behind him (in front of the cenotaph). Families of the dead are offering flowers and burning incense. They seem not to have noticed the crowd in the park nor heard the shouts and applause. To me they seem to be playing the part of the chorus in a Greek tragedy, adding dignity to the agony and ecstasy of the drama on the conference platform.”

From the standpoint of A-bomb survivors, Mr. Moritaki held fast to his position of “opposing nuclear tests by any nation,” even including these words in his address. However, the audience, bereft of support from the Socialist Party forces, who had already left the venue, gave a cold shoulder to Mr. Moritaki. Even booing was heard.

After the opening plenary, the Hiroshima Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs handed back authority over the conference to the Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs. Both Mr. Moritaki and Mr. Ito disappeared from the venue. Meanwhile, on the following day, August 6, 7,000 supporters of the Socialist Party and the General Council of Trade Unions held their own gathering in Hiroshima. That meeting led to the birth of the Japan Congress against A- and H-bombs.

Reflecting on the time, Mr. Kitanishi said, “I suppose that era hints at the weakness of citizens’ movements in Japan. When the first meeting of the World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs was held, the Japanese people were consumed with tension over the nuclear issue. But not at the time of the split. For mobilizing supporters and managing the financial side of the movement, it was inevitable that experienced activists would become the standard bearers of the movement. Academics were also completely caught up in that whirlwind.” Mr. Kitanishi remained involved in the conference to the end, and helped forge a draft resolution. But words expressing self-criticism over the split and efforts to reunify the organization were struck from the final statement, with the text evoking the anti-American and anti-imperialist sentiments of the Communist Party.

Leaving behind the labels of “exhausted” and “broken-hearted” for those in the movement, the summer of the split is now a thing of the past. Since that time, the campaign against atomic and hydrogen bombs has entered a long period of stagnation. The movement kept citizens and A-bomb survivors out in the cold and played party politics, which has left the future with a very high price to pay. The late A-bomb poet Shinoe Shoda composed this poem about the fracturing and transformation of the campaign.

After thorough introspection, I realize not atomic and hydrogen bombs but our “minds” will annihilate the human race.

[Reference] Hiroshima Notes by Kenzaburo Oe, translated by David L. Swain and Toshi Yonezawa.

(Originally published on May 28, 1995)