History of Hiroshima: 1945-1995 (Part 19, Article 2)

Mar. 10, 2013

Split in the Campaign Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs II

by Tetsuya Okahata, Staff Writer

Note: This article was originally published in 1995.

The campaign against atomic and hydrogen bombs, which developed into Japan’s largest mass movement, eventually suffered a shift in its nature when political parties intervened. The Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs, the pillar of the campaign, fractured in two, with the forces of the Socialist Party and the General Council of Trade Unions (Sohyo) in Japan on one side and Communist Party supporters on the other. Many citizens and A-bomb survivors then distanced themselves from the movement.

Japan’s campaign against atomic and hydrogen bombs no doubt had a huge impact on the worldwide peace movement and helped propel nuclear disarmament efforts. At the same time, its leaders are accountable for the disastrous tug-of-war they waged, which cast aside citizens and A-bomb survivors and brought gridlock to the campaign.

The Chugoku Shimbun examines twin images of the campaign against atomic and hydrogen bombs--one genuine, one false--through the lens of the ninth meeting of the World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs in 1963, when the split became a fait accompli, as well as the lives of two activists who were involved in the campaign for many years.

Two activists devote their lives to rival antinuclear organizations

In June 1988, two Japanese men entered an aging hotel located in New York City. With the third U.N. Special Session on Disarmament about to commence, the pair were watched intently by Japanese activists, full of emotion. The two men strolled at ease, mingling with the peace delegations from other nations which flooded the hotel lobby.

The men were Yoshikiyo Yoshida, now 69, former general secretary of the Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs, and Juro Ikeyama, 63, former vice director general of the Japan Congress against A- and H-bombs. In the 1970s, following the split in the campaign against atomic and hydrogen bombs, the two organizations were engaged in a fierce struggle and Mr. Yoshida and Mr. Ikeyama were young stalwarts serving as pillars and top debaters of their respective groups. They were worlds apart in their beliefs, so to speak. “I didn’t imagine such a time would come,” Mr. Yoshida said quietly, with feeling, to his acquaintance while in New York.

The two activists spent half their lives in the dusty offices of their anti-nuclear organizations, active participants in the disputes between the two groups. Then, as if turned away, they ultimately left the organizations that they had developed with such devotion. The men’s paths, so similar, mirrored the path of the twisting and turning campaign against atomic and hydrogen bombs itself.

Tracing back their lives as activists, we come upon an experience that they shared in the early days of their careers: the first peace march in Japan, held in 1958. The march, promoted by Atsushi Nishimoto, a Buddhist from Kochi Prefecture who was inspired by a similar action in England, involved a 1,000-kilometer trek from Hiroshima to Tokyo. After being expelled from Waseda University as a consequence of the fight against the anti-communist “Red Purge,” Mr. Yoshida joined the staff of the head office of the Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs when the organization was established in 1955. He was assigned to provide support for the peace march of 1958.

Mr. Yoshida named a student who had just joined the Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs to fill a staffing role for the march. This student, Mr. Ikeyama, had been suspended from the Tokyo University of Education for an indefinite period as a result of his involvement in a campaign that was opposed to the Subversive Activities Prevention Act. During this suspension, Mr. Ikeyama served as a reporter for a local newspaper in Bunkyo Ward, Tokyo, and witnessed people’s anger over the Bikini Incident and their fears of radioactive fallout. He was thrilled by the opposition to atomic and hydrogen bombs, which had spread mainly from neighborhood associations and women’s groups. “This is an extraordinary movement,” he thought.

When it came to the peace march, Mr. Ikeyama had no model to guide him; only youth and passion were on his side. “I didn’t have the slightest idea what preparations needed to be made,” he recalled. “All things considered, I find it kind of amazing that Mr. Yoshida would let an amateur like me have that responsibility.”

The peace march departed on June 20 from in front of the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims. When Mr. Yoshida crossed the threshold between Hiroshima City and Kure City, he was surprised to find Kenichi Matsumoto, then the mayor of Kure, and members of a women’s group waiting for them. The Kure residents had prepared hot water for the marchers to drink. “News of the march spread by word of mouth, and when we entered each new city or town, the mayor, members of women’s groups, and other well-wishers would be there waiting for us,” Mr. Yoshida said. “It was during the march that the notion of horizontal ties was established for the citizens’ movement.”

As the march moved toward Tokyo, people working in the fields would drop what they were doing and dash along paths between rice paddies to greet the marchers. After 62 days of these scenes of support, the march finally reached Tokyo and was met with confetti. At Hibiya Park, the goal of the long trek, 5,000 people turned out to greet the marchers. Some waved from the sides of the street while others offered cups of tea. The peace march had succeeded in unifying the public.

However, the moment the public’s voice lost strength, political parties stepped in. Bewildered by the ideological disputes between the forces of the Socialist Party and the General Council of Trade Unions (Sohyo) on one side, and supporters of the Communist Party on the other, ordinary people drifted away from the movement. Marches and gatherings became affairs of party mobilization. Mr. Yoshida himself came to realize clearly that the movement had become detached from the people.

Many years later, Mr. Yoshida still feels chagrin. “I was a leader of the movement, so I feel responsible for what happened,” he said. “Why couldn’t I have helped promote the point of view of an alliance among the various elements?”

Meanwhile, Mr. Ikeyama left the Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs in 1960. His departure was prompted by doubts he felt over slogans advanced by the organization that were unrelated to the campaign against atomic and hydrogen bomb, including its opposition to the efficiency rating system that was adopted by the Japanese government to evaluate teachers working at public schools. One day he attended a gathering to protest nuclear testing by the Soviet Union, but the turnout was small and the gathering was canceled. When he heard that the event had been a casualty of the conflict between the Socialist Party and the Communist Party, which was spilling over into the local chapters of the organization, he said to himself: “The movement is finished.”

The split in the campaign took place three year later, at the ninth meeting of the World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs. In 1965, the forces of the Socialist Party and the General Council of Trade Unions established the Japan Congress against A- and H-bombs. Mr. Ikeyama, hoping to relive the enthusiasm of the peace march, dedicated himself to the anti-nuclear campaign once again.

Meanwhile, the gulf separating the political parties showed no signs of being bridged. “A segregated organization.” “A campaign manipulated by certain political parties, by certain countries.” The slurs flew as the two sides waged battle over which was the “legitimate” organization opposed to atomic and hydrogen bombs.

At one point Mr. Yoshida was asked by Gene LaRoque, a former U.S. Navy Admiral who would become known for revealing that U.S. ships were carrying nuclear weapons into Japanese territory, if they were pursuing a ban on nuclear weapons or simply engaging in a squabble. It was a biting comment. Other countries gave a hard look at the fact that the antinuclear movement in Japan, the A-bombed nation, had suffered this bitter split. Hoping to reunify the campaign, Mr. Yoshida sought a solution.

But Mr. Ikeyama was critical of the argument made for unity. “Unifying organizations that are as incompatible as oil and water is impossible,” he said. “An easy compromise would mean the death of the movement.” Instead, he called for an alliance between the two organizations that involved respecting one another’s differing campaigns while making joint efforts for common challenges. With this rebuttal, Mr. Ikeyama directly confronted Mr. Yoshida’s advance for unity, and sparks were soon flying between the two, in the pages of newspapers and elsewhere.

On May 19, 1977, in the midst of this debate, Mr. Ikeyama was surprised by a bolt from the blue. Ichiro Moritaki, then chair of the Japan Congress against A- and H-bombs, and Nobuo Kusano, then director of the Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs, agreed to unify the two organizations by the end of the year. This was the so-called “5-19 agreement.” Just two days before, Mr. Ikeyama, within his organization, which included the Sohyo, elicited the final confirmation of the “theses on unification of the movement against atomic and hydrogen bombs,” whose central element was his alliance theory. “I thought Mr. Moritaki had understood it... The Sohyo did not tell me anything important,” Mr. Ikeyama said.

An expanded group of executive members from both organizations, a body which pursued the unification of the two groups and also established an executive committee to oversee the unification process, rebuffed Mr. Ikeyama’s wish to attend. Having managed the business affairs of the organization since assuming the post of vice director general in 1972, his pride was now shattered. Shortly after, Mr. Ikeyama left the administrative office with these parting words: “I have experienced the greatest humiliation of my life.”

Before his resignation, Mr. Ikeyama had bit his lip in frustration outside the room where the facilitators were gathering, a group which included Mr. Yoshida. When Mr. Yoshida heard the news that Mr. Ikeyama had resigned, he felt that it was a “hasty” decision. “There was a kind of telepathy between us,” he recalled. “After the two sides united, I thought we could work together...”

However, seven years later, in 1984, Mr. Yoshida himself was leaving his organization. He was forced out for “repeatedly taking action to benefit the enemy of the Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs, supported by the Sohyo and the Japan Congress Against A- and H-bombs.” Looking back, Mr. Yoshida said, “These were absurdly inadequate grounds for attacking me. I believe the Communist Party found that I was getting in the way of their goal, which involved turning the Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs into their subcontractor.” He was slapped with a censure motion from the organization he had helped establish and had dedicated roughly 30 years of his life.

After Mr. Yoshida was dismissed by the Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs, he set up a liaison office for the International Peace Bureau. One day, Mr. Ikeyama stopped by Mr. Yoshida’s office. It was the first time the two met since the split in the anti-nuclear movement. As they quietly shook hands, perhaps the dazzling sunlight that kissed the peace march of years before passed through their minds. The two men would go on to attend the U.N. Special Session on Disarmament together, described at the beginning of this article.

Mr. Ikeyama, as a critic on nuclear issues, still feels considerable concern over such matters. “We can’t judge the campaign against atomic and hydrogen bombs simply by looking at Japan,” he advised. “In Japan, the campaign was turned into a tool for partisan interests, because the leaders were unable to recognize the role they needed to play. But, globally, I think the world enduring the Cuban Missile Crisis, and the United States and the Soviet Union reaching nuclear disarmament agreements, were products of the long campaign against atomic and hydrogen bombs.”

Reflecting on the past, Mr. Yoshida said, “Throughout our campaigns, I was always conflicted about the presence of A-bomb survivors because they never sat at the center of the movement.” In 1990, Mr. Yoshida traveled to an anti-nuclear gathering held in Estonia. He encountered victims of the accident at the Chernobyl nuclear reactor, in the former Soviet Union, and discovered a new calling for his peace work.

“The world has feelings for the A-bombed city of Hiroshima that are more powerful than we can imagine,” Mr. Yoshida said. “The A-bombed city must respond to these feelings.” Continuing his peace efforts, he is now focused on providing medical assistance to the victims of the Chernobyl accident. And this time around, it is the sufferers of nuclear disaster who sit at the heart of the movement.

May 19 agreement

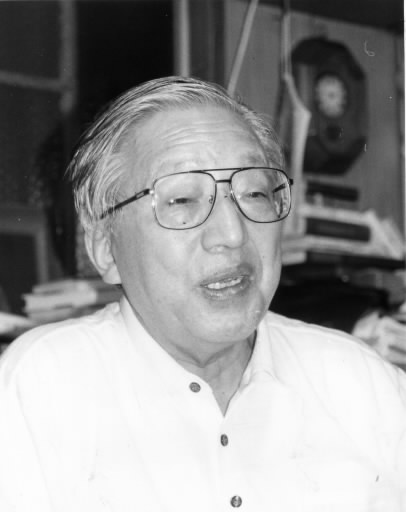

Nobuo Kusano, former director of the Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs

The handshake between Nobuo Kusano, director of the Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs (Gensuikyo), and Ichiro Moritaki, chair of the Japan Congress against A- and H-bombs, on May 19, 1977 led to the reunification of the two groups after a split that had lasted for 14 years. The crime of the atomic bombing was seared into the memories of these two aging scholars, and the reunification was the result of their persistence. “They had originally been one group, so it was strange that they were divided. That was all it amounted to really,” said Mr. Kusano, 85, in an interview at his home in Tokyo’s Shinagawa Ward.

“The Communist Party was opposed to reunification,” Mr. Kusano said. “But public opinion was overwhelmingly in favor of it.” Mr. Kusano said that prior to the “reunification drama” he pressed the Communist Party member who handled Gensuikyo matters as to whether the organization was subsidiary to the party or a public group. “He replied that it was a public group,” Mr. Kusano said. “I got him to give his word on that. If it was a public group then naturally it would reflect the popular will.”

As a pathologist at the University of Tokyo’s Institute for Infectious Disease, Mr. Kusano had participated in a survey that was conducted in Hiroshima just after the atomic bombing. Initially he conducted autopsies on Miyajima and found that the victims’ blood-forming function was impaired, clearly an effect of radiation. “This is unpardonable,” he thought to himself as he looked at the damaged internal organs.

Talks between the two sides got underway at the recommendation of the Nipponzan Myohoji sect of Buddhism. “Nichidatsu Fujii [founder of the sect] was great,” Mr. Kusano said. “He created a distinctive atmosphere in which we could get back together.” On May 18 Mr. Kusano and Mr. Moritaki met for the first time in 14 years at a Tokyo hotel.

Mr. Moritaki outlined his idea of “complementarity” by which the two organizations would proceed with their own endeavors but hold joint conferences. Mr. Kusano, on the other hand, stressed the need for “one conference, one undertaking.” Discussions continued after dinner, and Mr. Kusano ultimately agreed with Mr. Moritaki, who advocated absolute rejection of all uses of the atom, including nuclear power.

Thus a gap of 14 years was bridged. “It was the trend of the times,” Mr. Kusano said. “Things couldn’t get done through the efforts of individuals.” But in their hearts was a desire to “atone” for the atomic bombing. On the 19th they changed their agreement to one of categorical rejection of nuclear weapons rather than of all uses of the atom.

But they did not succeed in bringing about reunification of the two organizations, and the holding of joint conferences ended in 1986. In 1984 Mr. Kusano resigned under threat of a censure motion.

Mr. Kusano is now preparing to reprint a book first published in 1953 on the harm inflicted by the atomic bombing. “People still don’t understand how horrifying the effects of radiation are,” he said. “This time I will include a map of Japan with all the cities that were bombed marked in black. The map is almost completely covered in black. People will see that Japan was already done for by the time of the A-bombing and realize how absurd the theory that the A-bomb hastened Japan’s surrender is.” This is the conviction of this elderly scholar, who witnessed the atomic bombing.

[Reference] Hiroshima Notes by Kenzaburo Oe, translated by David L. Swain and Toshi Yonezawa.

(Originally published on May 28, 1995)