History of Hiroshima: 1945-1995 (Part 25, Article 2)

Mar. 16, 2013

Films

by Masami Nishimoto, Staff Writer

Note: This article was originally published in 1995.

There is not a wealth of literature or films dealing with the atomic bombing, in terms of either quantity or content. The author Masuji Ibuse once wrote, “A major event like Hiroshima is far too big to be the subject of a literary work. There’s too much material.” Nevertheless creative artists have attempted to capture the human condition on paper and on film through the atomic bombing.

One of those creative artists was Toshiyuki Kajiyama, who enjoyed a reputation as a popular writer. From the days of his literary youth in Hiroshima, he struggled to depict the atomic bombing, but he died without having fulfilled this secret ambition. Just after the atomic bombings, a Japanese film company made a documentary of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that recorded the devastation of those cities. For many years this film was referred to as the “phantom film,” and the Japanese-language version is still subject to censorship by the Japanese government.

Some aspects of the atomic bombings are still coming to light, and just as the suffering continues, there will be no “The End” when it comes to works on the theme of the A-bombings. For that reason there is still a need to create them.

Documentary made just after the A-bombing

Still censored by the government

The precious documentary film that captured the suffering of Hiroshima and Nagasaki a little over one month after the atomic bombings is known as “the phantom film” or the “faceless film” because it could not be screened in Japan for nearly 25 years. The Japanese-language version remains incomplete.

The film, titled “The General Effects of the Atomic Bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” is 2 hours and 45 minutes long.

The Japanese-language version was first shown in 1968. The Ministry of Education cut a 13-minute segment on the effects of the bombings on people, essentially censoring the film saying “it would be difficult to screen those cruel scenes for the ordinary public.” Those, however, are precisely the “effects of the atomic bomb.” Why is the original version of the documentary on the A-bombings, which was produced by Japanese people, in English?

The film was produced by Nippon Eigasha, a film company established as a quasi-governmental concern prior to the war.

Sueo Ito (now Inoue), 83, a resident of Nagasaki, was one of the four directors of “Effects.” Regarding the impetus for the documentary’s production he said, “Right after Nagasaki was bombed, we got a report that the ‘special bomb’ was an atomic bomb. It was decided we would cooperate with the news desk in making a record of what had happened and telling the world of the cruelty of the bombings via Red Cross headquarters in Geneva,” he said. “But Japan lost the war, and we had no money so we couldn’t proceed with the project. My home was in Isahaya (Nagasaki Prefecture), so I went on ahead alone.”

With three days’ worth of rice in a knapsack, Mr. Ito departed the company’s headquarters in the Ginza area of Tokyo on September 7. Amid the devastation of Hiroshima he scouted filming locations and took photographs.

During that time, crew members led by Ryuichi Kano, a producer, called on Yoshio Nishina of the Institute of Physical and Chemical Research (Riken) and others who had conducted a survey in Hiroshima on August 8 with engineering officers from the headquarters of the Imperial Japanese Army and asked for their cooperation in the filming. (Mr. Kano died in 1988 at the age of 84.) On September 14 a research council of the Ministry of Education established a Special Committee for the Investigation of A-bomb Damage, and Nippon Eigasha staff members were approved as the film crew for the documentary.

The 32-member film crew, which was divided into five teams, such as the “medicine team” and the “biology team,” gathered in Hiroshima. Filming began on September 23.

Hidetsugu Aihara, 86, leader of the “physics team,” conducted the negotiations with the members of the survey team. At his daughter’s home in Saitama Prefecture, he unfolded an old map from those days showing the hypocenter area of Hiroshima and recalled the filming of the barren landscape.

“We found particles of metal that had been melted by the thermal rays, but I didn’t have a close-up lens to photograph them,” he said. “We had a lighting technician, but there was no power. When it was dark inside we had no choice but to ask the injured who were able to get around to go outside.” Moving shots were filmed using a rattly French-made camera perched on a large two-wheeled cart or a bicycle-drawn cart.

Mr. Ito, who could not wait for the rest of the film crew, began filming in Nagasaki on September 16 with a cameraman from the Fukuoka branch of Nippon Eigasha.

The adverse conditions were no different from those in Hiroshima. Most of all, Mr. Ito said, they did not want to avert their eyes from the hellish scenes they saw such as a girl whose hair had fallen out and a mother and child clinging to each other for support. “The people we filmed at relief stations were in the underground morgue a few days later,” he said. Nevertheless, as a documentary filmmaker, he continued to film.

The rest of the crew arrived in Nagasaki and had begun filming on October 24 when an assistant was arrested near the hypocenter by the U.S. military, which was occupying the city. As leaders of the film crew, Mr. Ito and Mr. Aihara appeared before the Occupation Forces three days later, and the entire crew was ordered to leave immediately.

Thus began the vicissitudes and difficulties that the film underwent. In his account in “20 Years after the Bombing” Mr. Kano wrote, “GHQ ordered us to turn over all of our film related to the atomic bombings.”

On December 18 Mr. Aihara took the cans of 35 mm film to GHQ headquarters in Hibiya, Tokyo. Through an interpreter he stressed that without editing and narration the film would not make a proper documentary. The head of the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey’s film crew, who was called in hastily, agreed. He had been a cameraman at MGM Studios in Hollywood. But production of the film could only continue under the direction of the American survey team.

Editing took place in an office building across from the Imperial Palace, where the survey team was based, and at the facilities of Nippon Eigasha, which had been dissolved at the order of GHQ and had become a joint-stock company. A military policeman was posted outside the door of the room throughout the time Mr. Aihara was editing the film.

The English narration was done by Toshiro Shimanouchi, 86, who was then an information officer for the Ministry of the Interior and later served as Japan’s ambassador to Norway. “The first and last time I saw the film was when I did the narration,” he said. That was because the film made under the “Effects” title left Japan after a preview screening conducted by GHQ.

The May 16, 1946 edition of “Stars and Stripes” reported that a valuable film had been sent to Washington in advance of the nuclear tests on Bikini atoll. In order to maintain secrecy surrounding the effects of the A-bomb, the U.S. military seized not only the film itself but also 30,000 feet (about five and a half hours’ worth) of negative film taken for production of the film and took it out of Japan.

At some point the film came to be known as the “phantom film.” “Effects,” which was held by the U.S. Air Force, was not returned to Japan until 1967, 21 years later.

But, when preparing a Japanese-language version for release, the Japanese government cut a 13-minute segment dealing with the effects of the bombings on the human body. Many A-bomb survivors who saw the film were disappointed and felt that it did not fully depict the brutality of the atomic bomb, leading the film to be branded as the “faceless A-bomb film.”

The Ministry of Education stubbornly refused to accede to requests to release the film in its entirety. So the City of Hiroshima and local residents joined forces to produce a 29-minute film, “Hiroshima: A Document of the Atomic Bombing,” in 1970. After seeing the film at a preview, the author Kenzaburo Oe wrote, “Based on film that documented Hiroshima at the time of the A-bombing, this must be said to be the best film yet.”

The film included the segment on the human body that the Ministry of Education had cut from the other film. Why was that possible? Motoo Ogasawara, 68, who directed the film, said, “Because there was completely unedited film that Mr. Kano and Mr. Ito had preserved at great risk to themselves.”

The close scrutiny by the Strategic Bombing Survey did not ordinarily extend to the headquarters of Nippon Eigasha. So the four men secretly preserved the unedited rushes. Of course, if they had been discovered they would have been sentenced to hard labor for violating an order of the Occupation authorities.

According to Mr. Ito, the last of the four men still living, Mr. Kano could not abide the thought that important images of the devastation caused by the atomic bombings might be lost and was determined to preserve as much of the film as possible, even it was only one roll. “At Mr. Kano’s direction, from the negatives we picked out the scenes we thought were important and developed them twice,” Mr. Ito said. He had had the painful experience of having film that he had shot in Burma being burned by the Army Ministry just after Japan’s defeat in the war.

Former members of the film crew secretly kept more than 10,000 feet of film in a lab they set up in Tokyo. The film, which captured the devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, was eventually returned to Nippon Eiga Shinsha, the successor to Nippon Eigasha, and part of it was shown for the first time in newsreels in 1952. By that time most of the men who had participated in the filming of the A-bomb documentary had left the company.

Mr. Ito went to work at Nagasaki City Hall and later served as superintendent of schools. Mr. Aihara spent many years working with Mr. Kano on a scholarly compilation of documentary photographs of the A-bombing.

“As a film, it remains unfinished,” said Mr. Aihara. “It’s merely for the U.S. military.” Despite his age, Mr. Ito still displays the pluck and obsessiveness of a documentary filmmaker. “What kind of A-bomb documentary can it be with the segment on the effects on the human body cut?” he said.

“Effects,” which was shot on 35-mm film, was transferred to video in the U.S., and an uncut version can easily be obtained there. Seeing it is a moving experience. The City of Hiroshima has a 16-mm Japanese version on loan from the Ministry of Education, but screening of the film is limited to “scholarly and educational purposes” at “locations deemed suitable by the mayor,” so it has essentially been shelved.

The City of Nagasaki, which obtained the 35-mm film from the U.S., is working with the Japan Peace Museum, a citizens’ group in Tokyo, to release a complete Japanese-language version of the suppressed documentary.

As the 50th anniversary of the A-bombings approaches, the day is nearing when the seal on the “phantom film” will be broken. “We tried to capture evidence of the atomic bombings and their effects on human beings,” Mr. Ito said.

Akira Mimura: Member of U.S. survey team

Came from Hollywood to film aftermath of A-bombing

Following the filming by the Nippon Eigasha crew, the film crew of the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey arrived in Hiroshima in March 1946. Some of the vivid color film of the devastation that they took was shown in Japan in 1970 and caused a sensation. This led to the “10 Feet Film Project,” a campaign by private citizens to purchase U.S. documentary footage of the A-bombings.

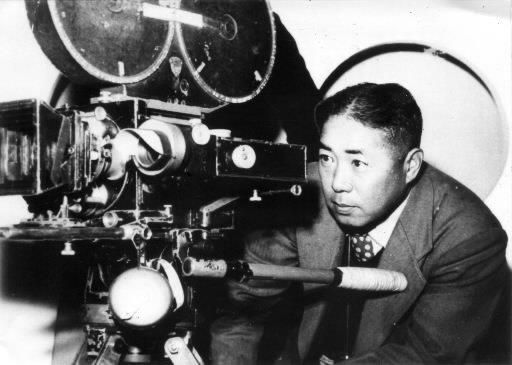

The film crew included one Japanese cameraman member: Akira Mimura. Mr. Mimura, a director who died in 1985 at the age of 84, earned a place in the history of Japanese movie-making. He was also the first Japanese allowed to become an official member of the cameramen’s union in Hollywood.

Mr. Mimura went to the U.S. in 1919 and studied camera technique at a photography school in New York. Amid strong anti-Japanese sentiment, through 1934 he honed his skills under the name Harry Mimura. After returning to Japan he went to work at Photo Chemical Laboratory, the forerunner of Toho Company, where he worked on many films, including “Sugata Sanshiro” with which Akira Kurosawa made his directorial debut.

Mr. Mimura’s English ability and his brilliant camera technique caught the attention of the Strategic Bombing Survey. While Nippon Eigasha had little equipment, the U.S. team boasted a wealth of supplies. Mr. Mimura recorded the aftermath of the A-bombing, making use of the sophisticated cinematographic skills he had acquired in Hollywood. He conducted rehearsals for the filming and was particular about the backgrounds of his shots of the devastation.

Miyoko Kudo, 45, a non-fiction writer who has written about Mr. Mimura’s life, said, “Regardless of the subject of his films, he was a highly professional person who was good at creating pictures. Even though he filmed for the U.S., he faithfully captured the effects of the atomic bombings.”

The documentary made by the Strategic Bombing Survey was closely monitored by the government for many years in the U.S. as well and was not available for viewing by the general public there until the late 1970s.

(Originally published on July 9, 1995)