Fukushima and Hiroshima: Time for “nuclear lessons” of the past to be applied

May 25, 2011

by the “Fukushima and Hiroshima” Reporting Team

Can humanity coexist with nuclear energy? This question is being posed to us anew. In the wake of the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant, sparked by the Great Eastern Japan Earthquake, soil and sea have become contaminated by radioactive materials. The situation has forced many people to evacuate the affected areas and live in limbo. What can the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which have been speaking out about the horror of radiation for 66 years, do now? The worst nuclear disaster in human history took place 25 years ago at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in the former Soviet Union. The Chugoku Shimbun highlights the lessons that must be learned from Hiroshima and Chernobyl.

It was a shocking sight. The Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant, drenched by the quake-triggered tsunami, lost all power and was unable to keep its nuclear fuel rods cool. A build up of heat inside the reactors led to an explosion of hydrogen, blowing away the walls of the buildings, and with them, the myth of “safe” nuclear energy. Then a large volume of radioactive materials began leaking into the environment from the crippled plant.

The accident was rated a “level 7” disaster, the worst on an international yardstick which assesses nuclear accidents, called the International Nuclear Event Scale (INES). Prior to this, the only other accident deemed “level 7” was the accident at Chernobyl. This provisional evaluation came from the Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency, a body within the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, and was based on the volume of radioactive leakage reaching 370,000 terabecquerels for the one-month period following the accident. (One terabecquerel equals one trillion becquerels.) The Nuclear Safety Commission of Japan put their estimate at 630,000 terabecquerels. The release of radioactive particles continues to this day.

No deaths have been reported due to radiation exposure. However, fears have mounted in the affected areas. The cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, two A-bombed cities, have moved swiftly in dispatching experts in radiation medicine and public health nurses to the stricken region. Using Fukushima Medical School as their base, the teams from Hiroshima and Nagasaki have been engaged in such efforts as providing medical examinations for the workers of the nuclear plant and checks of the thyroid gland in the local children.

The release of such radioactive materials as iodine and cesium has been confirmed. The area within a radius of 20 kilometers from the nuclear plant has been designated off-limits.

◇

Land that has long supported human activity has now been contaminated. The village of Iitate, in Fukushima Prefecture, is located about 40 kilometers northwest of the nuclear power plant. Tetsuji Imanaka, an assistant professor at the Kyoto University Research Reactor Institute (which focuses on the engineering of nuclear reactors), made an estimate of the level of contamination in the village's soil at the end of March. With regard to cesium, the area with the highest level recorded 4.06 million becquerels per square meter. This figure is about seven times the level of cesium that Belarus, a nation neighboring the Chernobyl plant, had set for the people who were authorized to emigrate into that nation following the accident at Chernobyl.

The sea has been contaminated as well. Some of the estimated 90,000 tons of contaminated water containing radioactive particles leaked from the crippled reactors and spilled into the sea. In the waters off Ibaraki Prefecture, radioactive iodine measuring 4,080 becquerels per kilogram was detected in launce caught by fisherman. The chairman of the National Federation of Fisheries Cooperative Associations expressed outrage at the Tokyo Electric Power Company, the operator of the troubled nuclear plant.

Following the accident, the Japanese government banned shipments of milk from the affected areas, a measure seen as wise. In the case of Chernobyl, a large number of children who inadvertently drank milk contaminated with radioactive iodine later suffered thyroid cancer. In this respect, the lesson learned from Chernobyl was heeded.

On the other hand, the results of measurements conducted by the System for Prediction of Environmental Emergency Dose Information (SPEEDI), which makes predictions on the spread of radioactive materials, were announced a month and a half after the accident, creating mistrust and unnecessary confusion among the public.

◇

A total of about 150,000 residents have been forced to evacuate from the area within a radius of 20 kilometers from the crippled plant and areas where high levels of radiation have been recorded. It remains unknown how the evacuees will be compensated for their losses. One issue that is now a subject of controversy is the standard of radiation exposure for protecting the health of children. The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology has set a standard of 20 millisieverts per year as the maximum level of exposure for the use of school playgrounds and restricts the use of these playgrounds when a level of radiation higher than the set benchmark is recorded. Still, there are voices calling strongly for a review of this standard.

The expertise that has accumulated in Hiroshima and Nagasaki over the years will now be put to use. How will the minds and bodies of the residents who remain in the affected areas be tended to, as they suffer from low levels of radiation exposure over an extended period of time? Such institutions as the Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF in Minami Ward, Hiroshima), Hiroshima University, and Nagasaki University, along with local institutions like Fukushima Medical School, will be engaged in efforts to monitor the health of some 150,000 people around the nuclear plant over the next 30 years.

On that day

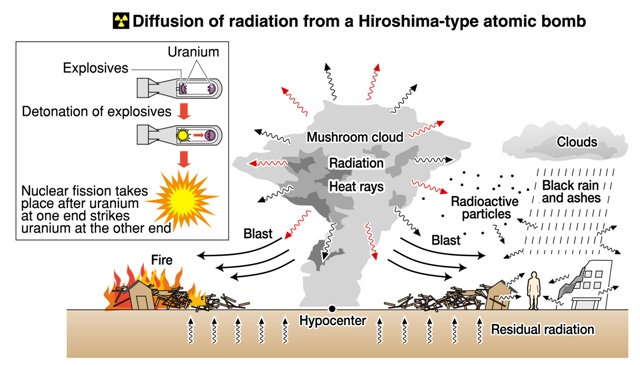

For the first time in history, human beings were attacked with an atomic bomb. The bomb, dropped on Hiroshima by the United States, employed uranium 235. (Plutonium 239 was used in the bomb dropped on Nagasaki.) The distribution of the energy released by the chain reaction of nuclear fission in the Hiroshima bomb is believed to be 50% blast, 35% heat, and 15% radiation. While approximately 3 to 5% low-enriched uranium 235 is used at nuclear power plants, the uranium used in nuclear bombs is enriched to nearly 100%.

Radioactive materials

Hiromi Hasai, a professor emeritus at Hiroshima University in nuclear physics said that the radioactive materials released in the explosion of the atomic bomb in Hiroshima consisted of gamma rays and neutron rays. The dose of exposure to those located 100 meters from the hypocenter is estimated at 435,000 millisieverts or 435 sieverts. At a distance of 1.7 kilometers the estimate is 262 millisieverts, and at 2 kilometers, 80 millisieverts.

The A-bomb explosion unleashed a fireball that was hundreds of thousands of degrees Celsius and spread radioactive materials in the form of vapor, though they naturally exist as solid substances. At the same time, the ground and buildings hit by the neutron rays turned radioactive. The “black rain” that fell in the aftermath of the atomic bombing contained radioactive materials as well.

Effects on the human body

It is estimated that 140,000 people (±10,000 people) in Hiroshima and 74,000 people in Nagasaki were dead by the end of 1945 as a result of the atomic bombings. RERF has been conducting a study involving the longevity of A-bomb survivors by investigating the cause of death of a total of 120,000, comprised of 94,000 survivors and 26,000 non-survivors. This includes A-bomb survivors who entered the city in the aftermath of the bombing. The foundation has also pursued an ongoing study on adult heath among some 23,000 people in which the subjects receive medical interviews and examinations every two years. The study has revealed that the higher the exposure dose, the higher the incidence and mortality rates of cancer, including leukemia.

Compensation

Those who hold the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate are exempt from paying medical expenses and the fees for health examinations that are conducted twice a year. A-bomb survivors who have fulfilled certain conditions can be provided with the Health Management Allowance (33,670 yen a month) or the Special Medical Allowance (136,890 yen a month). Patients with A-bomb microcephaly due to prenatal exposure to radiation, too, are entitled to receive allowances and other benefits. With regard to relief measures for the people who were exposed to the “black rain,” some have appealed for the designated area to be expanded.

Current situation

The number of holders of the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate, whom the Japanese and local governments officially define as “A-bomb survivors,” is approximately 228,000 as of the end of 2009. The issue of “certifying A-bomb diseases,” which involves the question of whether or not the illnesses suffered by A-bomb survivors were caused by the atomic bombing, remains to be resolved through litigation. As for second-generation A-bomb survivors, RERF announced the results of its study in 2007, saying: “There is no statistically significant difference between the children of survivors and the children of non-survivors.” But a follow-up study on second-generation survivors continues.

On that day

At Chernobyl, a number of wayward actions were taken by the workers at the plant, such as disabling the emergency cooling system of the reactor while continuing its operations. This led to the reactor spiraling out of control and, 40 seconds later, there was an explosion. As the plant used highly combustible black lead as the “moderator” for the nuclear fission chain reaction, the fire burned intensely. A large amount of radioactive materials were spewed into the air for 10 days before the fire was finally extinguished.

Radioactive materials

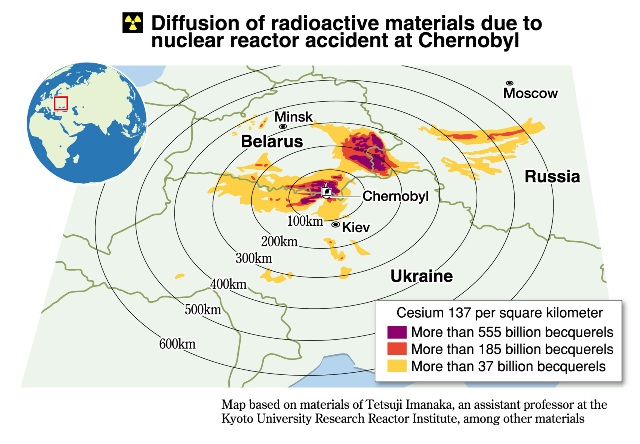

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) stated that the volume of radioactive materials, including iodine and cesium, released into the environment was 5.2 million terabecquerels. (One terabecquerel equals one trillion becquerels.) This figure is thought to be a dozen times the amount of radioactive materials leaked as a result of the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant. From Chernobyl, the radioactive materials, conveyed by the wind, were spread across the northern hemisphere. A week after the accident, radioactive particles from Chernobyl were even detected in rain water in Japan.

An on-site investigation conducted by Masaharu Hoshi, a professor of radiation physics at Hiroshima University's Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine, determined that a number of “hot spots,” where high levels of radiation were recorded, exist outside a radius of 30 kilometers from the Chernobyl plant, as rain containing radioactive materials fell on these areas. It was found that the radioactive materials did not spread in a concentric fashion.

Effects on the human body

Due to their work at the plant in the aftermath of the accident, 28 workers and emergency medical personnel died of acute effects brought on by their exposure to radiation. The firefighters who were engaged in battling the blaze were not fully equipped, lacking such things as radiation dose meters. The United Nations Science Committee, in its annual report in 2008, said that more than 6,000 people, and mainly children, developed thyroid cancer that is believed to be linked to the accident. The organization attributes the cause to internal exposure from the consumption of milk contaminated with radioactive iodine and through other means. The IAEA and other organizations estimate that approximately 4,000 people died as a consequence of effects wrought by the accident. The World Health Organization cites a figure of up to 9,000 people.

Compensation

Ukraine and its neighbor Belarus have provided special pensions and housing for sufferers of the nuclear accident, including people who were engaged in fire fighting in the wake of the disaster.

However, the government of Ukraine has indicated that it intends to terminate such compensation due to financial constraints. As a result, a large-scale demonstration took place in the capital of Kiev in April this year, waged by sufferers and their supporters.

Current situation

In April 2011, Mykola Kulinich, the Ukrainian ambassador to Japan, held a press conference to mark the 25th year since the accident. The ambassador said that areas totaling over 10,000 square kilometers in Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine have been contaminated, predicting that “the concentration of radiation through agricultural products and animals will last several decades.” The area within a radius of 30 kilometers from the nuclear power plant remains off-limits even today. With the “stone coffin” which shrouds the ruptured reactor now aging, radioactive materials may again leak out. Therefore, an effort is under way to build a new “iron coffin” which can remain intact for a hundred years.

(Originally published on May 15, 2011)

Can humanity coexist with nuclear energy? This question is being posed to us anew. In the wake of the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant, sparked by the Great Eastern Japan Earthquake, soil and sea have become contaminated by radioactive materials. The situation has forced many people to evacuate the affected areas and live in limbo. What can the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which have been speaking out about the horror of radiation for 66 years, do now? The worst nuclear disaster in human history took place 25 years ago at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in the former Soviet Union. The Chugoku Shimbun highlights the lessons that must be learned from Hiroshima and Chernobyl.

Fukushima: March 11, 2011

Health of people exposed to “low doses” of radiation over extended periods must be monitored long-term

Eyes of the world on Japan as it confronts the worst nuclear accident in its history

It was a shocking sight. The Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant, drenched by the quake-triggered tsunami, lost all power and was unable to keep its nuclear fuel rods cool. A build up of heat inside the reactors led to an explosion of hydrogen, blowing away the walls of the buildings, and with them, the myth of “safe” nuclear energy. Then a large volume of radioactive materials began leaking into the environment from the crippled plant.

The accident was rated a “level 7” disaster, the worst on an international yardstick which assesses nuclear accidents, called the International Nuclear Event Scale (INES). Prior to this, the only other accident deemed “level 7” was the accident at Chernobyl. This provisional evaluation came from the Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency, a body within the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, and was based on the volume of radioactive leakage reaching 370,000 terabecquerels for the one-month period following the accident. (One terabecquerel equals one trillion becquerels.) The Nuclear Safety Commission of Japan put their estimate at 630,000 terabecquerels. The release of radioactive particles continues to this day.

No deaths have been reported due to radiation exposure. However, fears have mounted in the affected areas. The cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, two A-bombed cities, have moved swiftly in dispatching experts in radiation medicine and public health nurses to the stricken region. Using Fukushima Medical School as their base, the teams from Hiroshima and Nagasaki have been engaged in such efforts as providing medical examinations for the workers of the nuclear plant and checks of the thyroid gland in the local children.

The release of such radioactive materials as iodine and cesium has been confirmed. The area within a radius of 20 kilometers from the nuclear plant has been designated off-limits.

◇

Land that has long supported human activity has now been contaminated. The village of Iitate, in Fukushima Prefecture, is located about 40 kilometers northwest of the nuclear power plant. Tetsuji Imanaka, an assistant professor at the Kyoto University Research Reactor Institute (which focuses on the engineering of nuclear reactors), made an estimate of the level of contamination in the village's soil at the end of March. With regard to cesium, the area with the highest level recorded 4.06 million becquerels per square meter. This figure is about seven times the level of cesium that Belarus, a nation neighboring the Chernobyl plant, had set for the people who were authorized to emigrate into that nation following the accident at Chernobyl.

The sea has been contaminated as well. Some of the estimated 90,000 tons of contaminated water containing radioactive particles leaked from the crippled reactors and spilled into the sea. In the waters off Ibaraki Prefecture, radioactive iodine measuring 4,080 becquerels per kilogram was detected in launce caught by fisherman. The chairman of the National Federation of Fisheries Cooperative Associations expressed outrage at the Tokyo Electric Power Company, the operator of the troubled nuclear plant.

Following the accident, the Japanese government banned shipments of milk from the affected areas, a measure seen as wise. In the case of Chernobyl, a large number of children who inadvertently drank milk contaminated with radioactive iodine later suffered thyroid cancer. In this respect, the lesson learned from Chernobyl was heeded.

On the other hand, the results of measurements conducted by the System for Prediction of Environmental Emergency Dose Information (SPEEDI), which makes predictions on the spread of radioactive materials, were announced a month and a half after the accident, creating mistrust and unnecessary confusion among the public.

◇

A total of about 150,000 residents have been forced to evacuate from the area within a radius of 20 kilometers from the crippled plant and areas where high levels of radiation have been recorded. It remains unknown how the evacuees will be compensated for their losses. One issue that is now a subject of controversy is the standard of radiation exposure for protecting the health of children. The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology has set a standard of 20 millisieverts per year as the maximum level of exposure for the use of school playgrounds and restricts the use of these playgrounds when a level of radiation higher than the set benchmark is recorded. Still, there are voices calling strongly for a review of this standard.

The expertise that has accumulated in Hiroshima and Nagasaki over the years will now be put to use. How will the minds and bodies of the residents who remain in the affected areas be tended to, as they suffer from low levels of radiation exposure over an extended period of time? Such institutions as the Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF in Minami Ward, Hiroshima), Hiroshima University, and Nagasaki University, along with local institutions like Fukushima Medical School, will be engaged in efforts to monitor the health of some 150,000 people around the nuclear plant over the next 30 years.

Hiroshima: August 6, 1945

Certification of A-bomb diseases continues to the present

On that day

For the first time in history, human beings were attacked with an atomic bomb. The bomb, dropped on Hiroshima by the United States, employed uranium 235. (Plutonium 239 was used in the bomb dropped on Nagasaki.) The distribution of the energy released by the chain reaction of nuclear fission in the Hiroshima bomb is believed to be 50% blast, 35% heat, and 15% radiation. While approximately 3 to 5% low-enriched uranium 235 is used at nuclear power plants, the uranium used in nuclear bombs is enriched to nearly 100%.

Radioactive materials

Hiromi Hasai, a professor emeritus at Hiroshima University in nuclear physics said that the radioactive materials released in the explosion of the atomic bomb in Hiroshima consisted of gamma rays and neutron rays. The dose of exposure to those located 100 meters from the hypocenter is estimated at 435,000 millisieverts or 435 sieverts. At a distance of 1.7 kilometers the estimate is 262 millisieverts, and at 2 kilometers, 80 millisieverts.

The A-bomb explosion unleashed a fireball that was hundreds of thousands of degrees Celsius and spread radioactive materials in the form of vapor, though they naturally exist as solid substances. At the same time, the ground and buildings hit by the neutron rays turned radioactive. The “black rain” that fell in the aftermath of the atomic bombing contained radioactive materials as well.

Effects on the human body

It is estimated that 140,000 people (±10,000 people) in Hiroshima and 74,000 people in Nagasaki were dead by the end of 1945 as a result of the atomic bombings. RERF has been conducting a study involving the longevity of A-bomb survivors by investigating the cause of death of a total of 120,000, comprised of 94,000 survivors and 26,000 non-survivors. This includes A-bomb survivors who entered the city in the aftermath of the bombing. The foundation has also pursued an ongoing study on adult heath among some 23,000 people in which the subjects receive medical interviews and examinations every two years. The study has revealed that the higher the exposure dose, the higher the incidence and mortality rates of cancer, including leukemia.

Compensation

Those who hold the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate are exempt from paying medical expenses and the fees for health examinations that are conducted twice a year. A-bomb survivors who have fulfilled certain conditions can be provided with the Health Management Allowance (33,670 yen a month) or the Special Medical Allowance (136,890 yen a month). Patients with A-bomb microcephaly due to prenatal exposure to radiation, too, are entitled to receive allowances and other benefits. With regard to relief measures for the people who were exposed to the “black rain,” some have appealed for the designated area to be expanded.

Current situation

The number of holders of the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate, whom the Japanese and local governments officially define as “A-bomb survivors,” is approximately 228,000 as of the end of 2009. The issue of “certifying A-bomb diseases,” which involves the question of whether or not the illnesses suffered by A-bomb survivors were caused by the atomic bombing, remains to be resolved through litigation. As for second-generation A-bomb survivors, RERF announced the results of its study in 2007, saying: “There is no statistically significant difference between the children of survivors and the children of non-survivors.” But a follow-up study on second-generation survivors continues.

Chernobyl: April 26, 1986 (local time)

Internal exposure transcends national borders

On that day

At Chernobyl, a number of wayward actions were taken by the workers at the plant, such as disabling the emergency cooling system of the reactor while continuing its operations. This led to the reactor spiraling out of control and, 40 seconds later, there was an explosion. As the plant used highly combustible black lead as the “moderator” for the nuclear fission chain reaction, the fire burned intensely. A large amount of radioactive materials were spewed into the air for 10 days before the fire was finally extinguished.

Radioactive materials

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) stated that the volume of radioactive materials, including iodine and cesium, released into the environment was 5.2 million terabecquerels. (One terabecquerel equals one trillion becquerels.) This figure is thought to be a dozen times the amount of radioactive materials leaked as a result of the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant. From Chernobyl, the radioactive materials, conveyed by the wind, were spread across the northern hemisphere. A week after the accident, radioactive particles from Chernobyl were even detected in rain water in Japan.

An on-site investigation conducted by Masaharu Hoshi, a professor of radiation physics at Hiroshima University's Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine, determined that a number of “hot spots,” where high levels of radiation were recorded, exist outside a radius of 30 kilometers from the Chernobyl plant, as rain containing radioactive materials fell on these areas. It was found that the radioactive materials did not spread in a concentric fashion.

Effects on the human body

Due to their work at the plant in the aftermath of the accident, 28 workers and emergency medical personnel died of acute effects brought on by their exposure to radiation. The firefighters who were engaged in battling the blaze were not fully equipped, lacking such things as radiation dose meters. The United Nations Science Committee, in its annual report in 2008, said that more than 6,000 people, and mainly children, developed thyroid cancer that is believed to be linked to the accident. The organization attributes the cause to internal exposure from the consumption of milk contaminated with radioactive iodine and through other means. The IAEA and other organizations estimate that approximately 4,000 people died as a consequence of effects wrought by the accident. The World Health Organization cites a figure of up to 9,000 people.

Compensation

Ukraine and its neighbor Belarus have provided special pensions and housing for sufferers of the nuclear accident, including people who were engaged in fire fighting in the wake of the disaster.

However, the government of Ukraine has indicated that it intends to terminate such compensation due to financial constraints. As a result, a large-scale demonstration took place in the capital of Kiev in April this year, waged by sufferers and their supporters.

Current situation

In April 2011, Mykola Kulinich, the Ukrainian ambassador to Japan, held a press conference to mark the 25th year since the accident. The ambassador said that areas totaling over 10,000 square kilometers in Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine have been contaminated, predicting that “the concentration of radiation through agricultural products and animals will last several decades.” The area within a radius of 30 kilometers from the nuclear power plant remains off-limits even today. With the “stone coffin” which shrouds the ruptured reactor now aging, radioactive materials may again leak out. Therefore, an effort is under way to build a new “iron coffin” which can remain intact for a hundred years.

(Originally published on May 15, 2011)