Fukushima and Hiroshima, Part 3 [Special]

Jul. 25, 2011

Peaceful uses of nuclear energy: Hiroshima’s role

by the “Fukushima and Hiroshima” reporting team

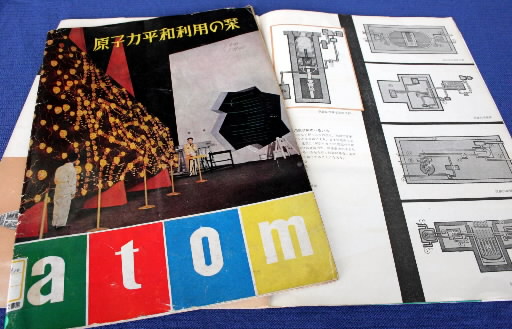

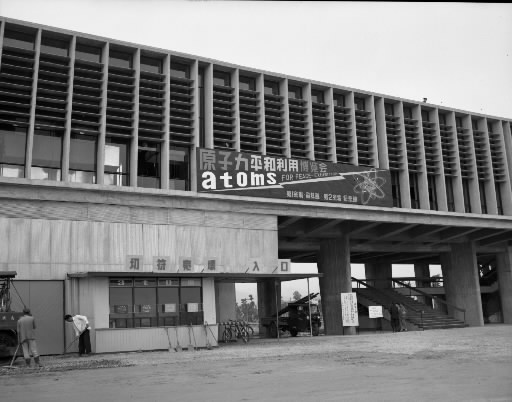

1956 exhibition on peaceful uses of nuclear energy at Peace Memorial Museum

This summer will mark the 66th anniversary of the atomic bombing. In light of the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant, Hiroshima is taking another look at where it has been and how it has addressed the issue of the “peaceful uses” of nuclear energy.

Nuclear energy was introduced to Japan as a visionary form of energy about a decade after World War II as the nation rushed to rebuild. The notion that it was completely different from military use for nuclear weapons was common in Hiroshima as well. In 1956 an exhibition on the peaceful uses of nuclear energy was held at Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. Even after that, the anti-nuclear and peace movements devoted little attention to the issue of nuclear energy. Ultimately, the military and peaceful uses of nuclear energy were regarded separately. In this article the Chugoku Shimbun takes a look at that history.

Exhibition draws 110,000 visitors: Uniformly positive coverage

Models and panel displays: Introduction of advanced technology

Every year about 1.3 million people from Japan and abroad visit the Peace Memorial Museum, which displays personal belongings of victims of the atomic bombing, a tile melted by the heat of the blast and other items. The museum opened in 1955. Since then those items, which convey the horror of the atomic bombing and the fearfulness of radiation, have been removed from the museum only once: for 22 days starting May 27, 1956 for an exhibition on the peaceful uses of nuclear energy.

At the instigation of the United States, the exhibition was held in Europe and South America as well as Asia. It was first held in Japan at a venue in Tokyo in November and December 1955 under the aegis of the U.S. embassy and the Yomiuri Shimbun newspaper company. From there it traveled to 10 more cities through August 1957 and attracted a total of 2.6 million visitors.

According to articles in the Chugoku Shimbun published at the time of the exhibition, the items on display in Hiroshima included a full-scale model of an experimental nuclear reactor, a model illustrating a nuclear fission reaction that used electric lights and panel displays that introduced nuclear physicists. About 110,000 people visited the exhibition.

The “Magic Hand,” a type of mechanical arm, was particularly popular. The arm, which was originally designed to handle dangerous radioactive materials, was operated by some visitors to pick up a brush and write “heiwa” (peace) and “genshi ryoku” (nuclear energy).

The exhibition was sponsored by the Chugoku Shimbun along with Hiroshima Prefecture, the City of Hiroshima, Hiroshima University and the American Culture Center in Hiroshima. It received extensive coverage throughout the paper at every juncture, including special feature pages on two occasions.

At the same time, news coverage also conveyed the impressions of atomic bomb survivors. In an interview, Ichiro Moritaki, then director of Hiroshima Gensuikin, complained about the exhibition saying, “I understand the positive aspects [of peaceful uses], but what are we going to do to eliminate the risk posed by the ‘ashes of death’? I’d like them to show something that addresses that question.”

In Japan the traveling exhibition was overseen by Matsutaro Shoriki, president of the Yomiuri Shimbun newspaper company. In 1955 he was elected to the House of Representatives for the first time with a platform that advocated the peaceful uses of nuclear energy. He also served as the first chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission of Japan. In tandem with Yasuhiro Nakasone, who later became prime minister, and others he promoted nuclear energy policy. Mr. Shoriki was referred to as the “father of nuclear energy in Japan.”

In April and May 1958, two years after the exhibition, an exposition on the rebuilding of Hiroshima was held in the city. As one of the venues for the expo, Peace Memorial Museum was temporarily renamed the “Nuclear Energy and Science Museum.” Most of the same items that had been displayed in the exhibition on the peaceful uses of nuclear energy were displayed alongside materials related to the atomic bombing.

Fears of backlash: U.S. adopts appeasement policy

Concern about reaction in Hiroshima

The global strategy of the U.S. can be seen in the selection of Hiroshima as one of the sites for the exhibition on the peaceful uses of nuclear energy 11 years after the atomic bombing.

U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower delivered his “Atoms for Peace” speech at the United Nations in December 1953. Four months before that, the Soviet Union had successfully conducted its first test of a hydrogen bomb. It is believed that the U.S. was attempting to check the influence of the Soviet Union, which was rapidly proceeding with the development of nuclear weapons, by offering technical support for the construction of nuclear power plants to friendly powers and non-aligned nations.

Then in March 1954 the Japanese tuna fishing boat Daigo Fukuryu Maru (Lucky Dragon No. 5) was exposed to radiation as a result of the test of a hydrogen bomb conducted by the U.S. on Bikini Atoll. After that, a petition drive in support of banning atomic and hydrogen bombs which had been launched in Tokyo, spread throughout the country.

“The U.S. was afraid that anti-nuclear sentiment would lead to anti-American sentiment,” said Mitsuo Ikawa, a professor of communication and media studies at Rikkyo University. “The exhibition on the peaceful uses of nuclear energy was part of its appeasement policy.” The U.S. Information Agency, a government body, conducted a survey of visitor attitudes at six of the exhibition venues. Prof. Ikawa obtained a copy of the report from the U.S. National Archives and analyzed it.

“The USIA was particularly interested in the results of the survey in Hiroshima,” he said. “They felt that if there was a positive reception here the resistance of the Japanese to nuclear energy could be overcome.” Prof. Ikawa said that in addition to being included in the overall report, the survey’s findings in Hiroshima were presented in a special report, which stated that the exhibition in Hiroshima had “succeeded beyond expectations” and “was supported by local leaders.”

Anti-nuclear movement and nuclear energy

Conflicts along party lines: Failure to have meaningful discussion

Opposition in late ’60s

Over the years Hiroshima has consistently called for “No More Hibakusha.” But the fact nuclear energy as well as nuclear weapons could cause people to become hibakusha has not always been recognized or asserted by the members of the ban-the-bomb and atomic bomb survivor movements.

Hiroshima first confronted the issue of the peaceful uses of nuclear energy in 1955 when U.S. Congressman Sidney Yates proposed building the first nuclear power plant in Hiroshima to “make the atom an instrument for kilowatts rather than killing.”

There was little support for the project, which many felt should not be accepted without careful consideration, and ultimately it came to nothing, but Hiroshima Mayor Shinso Hamai welcomed it, saying it would serve as a memorial to the victims of the atomic bombing.

The exposure to radiation of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru and the nationwide ban-the-bomb petition drive that it inspired led to the holding of the first World Conference against A- and H- Bombs that same year. But the goal of the movement remained a ban on the military use of the atom.

In 1956 the exhibition on the peaceful uses of nuclear energy was held in Hiroshima. The peaceful uses of nuclear energy were also the subject of a section meeting during the second World Conference against A- and H- Bombs, which was held in Nagasaki that year. The group reviewed actual examples of peaceful uses, and reportedly no critical comments were made during the discussions.

Makoto Kitanishi, a professor emeritus at Hiroshima University, was a member of the conference’s secretariat from its first year. “Nuclear energy was a symbol of scientific and technical progress. It was unthinkable to criticize science,” he said, recalling those times.

Afterwards there was a growing conflict at the world conference between the Communist Party and Socialist Party factions over issues such as whether or not the possession of nuclear weapons by the Soviet Union should be condoned. Finally, at the ninth conference in 1963 the two factions split. Since then the Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs (Gensuikyo) and the Japan Congress Against A- and H-Bombs (Gensuikin), which was formed after the split, have held separate world conferences every year. In November 1961 the Democratic Socialist Party and other parties formed a new organization, the National Council for Peace and Against Nuclear Weapons, to promote the banning of atomic and hydrogen bombs. The council took a positive stance on the peaceful uses of nuclear energy. A split took place in the organization for atomic bomb survivors as well leading to two separate organizations in Hiroshima Prefecture that share the name Hidankyo.

People first began to question the peaceful uses of nuclear energy in the late 1960s. At the world conference it sponsored in 1971 Gensuikin first took up the cause under the central slogan of “No nuclear power.” In 1975, the late Ichiro Moritaki, who was a professor emeritus at Hiroshima University and the chair of the organization, advocated complete rejection of all uses of the atom, including nuclear energy.

Between 1977 and 1985 Gensuikin and Gensuikyo managed to hold unified conferences once again, but they continued to avoid putting the issue of nuclear energy on the agenda for these unified conferences in order to prevent conflicts along party lines that would lead to another split. Some elements of the ban-the-bomb movement and citizens’ groups pursued activities that called into question all uses of nuclear energy. This effort, which was centered on the movement to oppose the construction of a nuclear power plant at Kaminoseki in Yamaguchi Prefecture, failed to inspire widespread public opinion against nuclear energy.

Meanwhile accidents occurred at the nuclear power plant in Chernobyl in Ukraine, at the uranium reprocessing facility in Tokaimura and at the nuclear power plant in Fukushima.

“There was not widespread awareness in Hiroshima that harm resulting from nuclear energy is not caused only by atomic bombs,” said Yukio Yokohara, former director of Hiroshima Gensuikin. “Now is the time to remind ourselves of the significance of Mr. Moritaki’s statement that ‘the atom and human beings can not coexist.’”

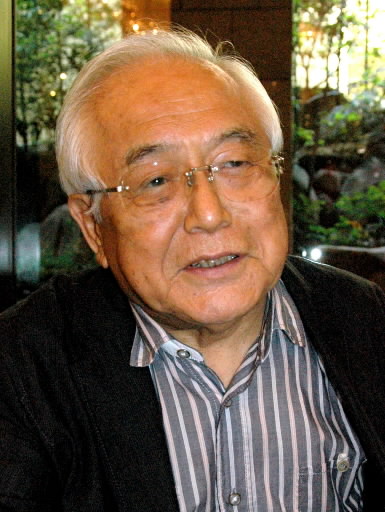

An interview with Takashi Hiraoka, former reporter for the Chugoku Shimbun and mayor of Hiroshima in the 1990s

Insensitive to risks of nuclear power

After working as a reporter for the Chugoku Shimbun, Takashi Hiraoka, 83, served as mayor of the City of Hiroshima for two terms in the 1990s. The Chugoku Shimbun asked him about his views on nuclear power over the years. “I accepted nuclear power as a necessary evil for enjoying the benefits of civilization,” he said. He expressed an awareness of the need to reconsider the “peaceful uses” of nuclear energy in light of the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant. The following are excerpts from the interview.

How did you feel about the exhibition on the peaceful uses of nuclear energy that was held in Hiroshima?

At the time I had been working for the Chugoku Shimbun for four years. I was working in the page editing department where we wrote headlines for articles. I was very impressed by the exhibition. Everything it talked about was like a dream. I particularly remember the “Magic Hand” that was on display. During the war the people of Japan believed in having a strong spirit and were prepared to fight with bamboo spears. In reaction to that, I think many people had a blind faith in science and technology.

Was the news coverage of the exhibition positive?

The race with the Soviet Union to develop nuclear weapons was going on, and the U.S. was concerned about the growing anti-American, anti-nuclear mood in Japan. Looking back, the exhibition neglected the negative aspects of nuclear energy in an attempt to “brainwash” the people of Japan. The coverage by the Chugoku Shimbun was all positive. News coverage had been censored by the General Headquarters [of the Allied Powers] until 1952, and we couldn’t adequately cover the harmful effects of the radiation from the atomic bombing. And people had gotten in the habit of just swallowing whatever the headquarters of the Imperial Japanese Army said during the war.

After that how was nuclear power characterized in terms of coverage of the anti-nuclear and peace movements?

As a reporter I also wrote a lot of articles on the issue of the atomic bomb survivors in South Korea and advocating the abolition of nuclear weapons. I looked at the dangers of the military use of nuclear power, but I was not sensitive to the risk of nuclear-related harm that could result from the use of nuclear energy. I regret that now.

How about when you were mayor?

In my peace declarations at the peace memorial ceremony I never expressed opposition to the use of nuclear power plants. In 1991, the first year I was mayor, I merely called on Hiroshima to lead the world in providing aid to the victims of the [1986] Chernobyl disaster. Perhaps one reason was that there were no nuclear power plants in Hiroshima. And I felt that the paradox of opposing nuclear energy while using electricity generated by nuclear power plants was like the deceit of calling for the abolition of nuclear weapons while being protected under the nuclear umbrella.

In light of the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant, how do you feel now?

I now realize that there is no distinction between the military and peaceful uses of nuclear energy in terms of the threat to humankind of radioactive materials. In today’s profit-seeking society the warnings sounded by research have been distorted and ignored. It is frightening. We do not necessarily need to stick with nuclear power. If it’s a choice between economics and life, the answer is clear.

Takashi Hiraoka

Born in Osaka in 1927. Graduate of Waseda University. Became a reporter at the Chugoku Shimbun in 1952. Served as chief editor for seven years starting in 1975. Became president of RCC Broadcasting Co., Ltd. in 1986. Elected mayor of Hiroshima in 1991 and served for eight years (two terms).

(Originally published July 13, 2011)