Fukushima and Hiroshima: Impact on the A-bombed city, Part 3 [1]

Jul. 25, 2011

Article 1: “Peaceful use” a deception

by Yumi Kanazaki and Yoko Yamamoto, Staff Writers

The crisis at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant continues unabated. In this series of articles, the Chugoku Shimbun will explore the impact of the nuclear crisis on the A-bombed city of Hiroshima, which directly experienced the horror of radiation as a consequence of the atomic bombing and has since continued to appeal for nuclear abolition and peace.

Expected nuke-led prosperity ends in disappointment

“Atomic power is frightful. If it is used badly the human race will become extinct. However, if it is well used, the more it is used the happier humanity will be, and peace will surely come.”

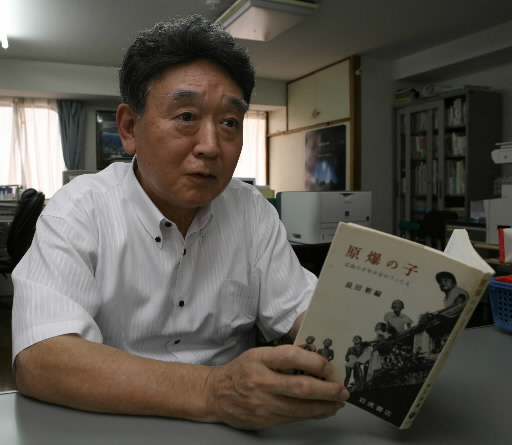

This passage is found in “Genbaku no Ko” (“Children of the A-bomb”), a collection of essays about A-bomb experiences that was published in 1951, six years after the atomic bombing. A child's hope for the peaceful use of nuclear power, described by Masaaki Tanabe, 73, when he was in his second year of junior high school, was selected for inclusion in the book, one of 105 essays from the 1,000 accounts that were submitted.

Sixty years have passed since the book was published. With a copy of the book in hand, Mr. Tanabe, a resident of Nishi Ward, Hiroshima, spoke as if forcing the words out: “I'm ashamed of my perception of things back then. The idea of 'peaceful use' was nothing but a deception.”

In March of this year, the nuclear crisis erupted at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant. Even four months later, the nuclear plant is still spewing radioactive materials into the environment.

Mr. Tanabe’s parents’ home stood just east of the former Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall (now, the Atomic Bomb Dome). After he was evacuated to Yamaguchi Prefecture, the atomic bomb exploded almost right above his parents' home. Two days later, he and his grandmother entered the city, now burnt to the ground. They searched for his family, and were exposed to the bomb's residual radiation. Afterwards, he suffered from acute symptoms of radiation sickness, including diarrhea and fever.

Perfect restoration of stricken communities is impossible

Losing his parents, his younger brother, and his home was a traumatic experience for the seven-year-old boy. Consumed with anger for which he had no outlet, Mr. Tanabe felt as if his heart would burst. “If only it hadn't been for the atomic bombing,” he thought. It was through his enthusiastic support of the “peaceful use” of nuclear energy, he said, that he was somehow able to cope.

Since 1997, Mr. Tanabe has spearheaded a project in which the townscape and the daily life of the hypocenter area, a community that once stood beneath the explosion of the atomic bomb and had included his own home, is being restored via computer animation. He is now expanding the restoration to a one-kilometer radius from the hypocenter. While Mr. Tanabe is engaged in this work, his thoughts turn toward the displaced residents of Fukushima Prefecture. His heart aches. “It will be impossible to perfectly 'restore' those lost towns,” he said, “because the radiation has not only affected people's lives and health, it has deprived them of the culture and history of their communities.”

Efforts focused on elimination of weapons

The proclamation made by the Japan Confederation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers Organizations, at its Establishment Meeting in 1956, stated: “Atomic power, which has a tendency to follow the road to destruction and extermination, must absolutely be converted to a servant for the happiness and prosperity of humankind. This is the only desire we hold as long as we live.”

Terumi Tanaka, the current secretary general, looked back on those days and said, “I think that there were hopes among A-bomb survivors that nuclear power, which had brought on us a bitter fate, would now be utilized for a peaceful purpose.”

A-bomb survivors, who were suffering from damaging effects to their health, difficult living conditions, and discrimination, continued to appeal for relief measures, national compensation and nuclear abolition, and developed their A-bomb-related campaigns. However, in the 1960s, affected by deepening discord within the movement opposed to atomic and hydrogen bombs, the Japan Confederation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers Organizations faced a crisis that threatened to splinter the group.

“We had no choice but to confine our attention to the elimination of nuclear weapons and do our best to act in concert,” Mr. Tanaka explained. “Naturally, the subject of nuclear power plants became a topic that was taboo.”

Even those who knew the horror of nuclear weapons firsthand were unable to express their strongly-held views, whether for or against, regarding the “peaceful use” of nuclear energy. Withholding these views, for the sake of surviving as individuals and as organizations, was a difficult decision for the survivors. It was not until three months after the nuclear crisis began that the Japan Confederation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers Organizations stepped into the new domain of calling for nuclear power plants to be eliminated.

(Originally published on July 13, 2011)