Fukushima and Hiroshima: 9 months after the disaster

Dec. 12, 2011

Few signs of recovery

by Seiji Shitakubo, Yoko Yamamoto and Yo Kono, Staff Writers

It will soon be nine months since the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant. The first hard frost of the winter has already been observed in Fukushima Prefecture, and the low temperature is regularly below freezing these days. More than 150,000 people continue to live as evacuees. Invisible radioactive materials prevent them from resuming their lives and returning to their homes. Various initiatives toward rebuilding have begun, but a host of issues such as decontamination and the disposal of debris, cloud the view of the future. We made a December visit to Fukushima.

Decontamination: Massive amount of contaminated soil

Search for disposal sites

The sound of heavy equipment fills the air in a peaceful mountain village in the Onami district on the outskirts of Fukushima City. Located approximately 55 km northwest of the nuclear power plant, this area is a hot spot with a high level of radiation. Workers can be seen using heavy equipment to remove soil from residents’ yards and high-pressure water sprayers to rinse roof tiles. Radioactive decontamination began here in October, the first of 19 areas of the city where such work will be undertaken.

About 1,300 people live in approximately 360 households in the Onami district. The amount of radiation emitted in the yard of farmer Kii Kato, 73, went from about 3 microsieverts per hour before decontamination to half that afterwards.

The decontamination work, which will go into full swing in January, poses many challenges. According to an estimate by the Ministry of the Environment, the targeted areas, where the annual dose of radiation exceeds 1 millisievert, cover 11,600 square km in Fukushima, Miyagi and Tokyo and seven other prefectures. The central government projects that a budget of approximately 1.2 trillion will be needed for this fiscal year and next fiscal year alone.

Where will the radioactive soil and leaves be taken? According to the central government’s plan, for the first three years they will be stored temporarily in areas set up in each municipality. After that they will be gathered at a large-scale interim storage facility for 30 years before being taken to a final disposal site.

But the reality of the situation is grim. The acquisition of sites for temporary storage is not proceeding as expected because residents have expressed opposition to the location of storage facilities in their area citing fears of contamination of groundwater and saying they object to having waste brought to the vicinity of their houses and property. And can vast forests be completely decontaminated? The government has yet to present concrete plans for this.

Formulation of plan

Central government, Fukushima Prefecture slow to act

Iwate and Miyagi prefectures, which sustained enormous damage in the Great East Japan Earthquake, had prepared rebuilding plans by September. Meanwhile Fukushima Prefecture’s formulation of its plan is lagging. The prefecture’s draft was broadly endorsed by an advisory panel of experts and others in late November. The plan includes 710 projects such as support for farmers and measures to assist evacuees. The prefecture has said it will seek the opinions of prefecture residents and would like to finalize the plan by the end of the year.

After the disaster, the prefecture, which had joined in promoting nuclear power, was quick to change its tune stating, “The central government is entirely responsible for the accident at the nuclear power plant.” To the residents this looked like the prefecture was shifting the blame. At a meeting of the advisory panel a member flatly told prefectural officials, “The prefecture should tell the central government what it wants it to do instead of ‘hakomono’ public works projects involving squabbles by government offices over their interests.” Prefectural officials were hard put to reply.

From the start the central government’s efforts toward rebuilding were slow. A schedule for the decontamination work was not announced until late October, more than seven months after the disaster. During that time there were political struggles over issues such as a change of prime minister, and time was wasted.

The word “rebuilding” has little resonance for the area’s residents. Those who are living as evacuees in temporary housing and other facilities all lament the fact that the future is uncertain.

Rebuilding-related Budget and Projects

In July the government announced its intention to spend 23 trillion over the next 10 years for reconstruction and recovery in the wake of the Great East Japan Earthquake. The third supplementary budget, which was approved in November, includes 9.24 trillion for reconstruction projects.

In January the Act on Special Measures Concerning the Handling of Radioactive Pollution will go into effect. This law has various provisions including one stating that the central government will process waste for which the concentration of contamination exceeds a certain standard. During next year’s ordinary session of the Diet a bill tentatively titled the Act on Special Measures Concerning the Rebuilding and Rebirth of Fukushima will be submitted, and other measures such as tax breaks offered by the disaster area to businesses are scheduled to be taken.

In areas where the annual dose of radiation is less than 20 millisieverts, municipalities will do the decontamination themselves. The central government will assume responsibility for decontamination of the no-entry zone within 20 km of the nuclear power plant and areas where the annual dose of radiation is 20 millisieverts or more. The cost will initially be borne by the government but ultimately paid by the Tokyo Electric Power Company.

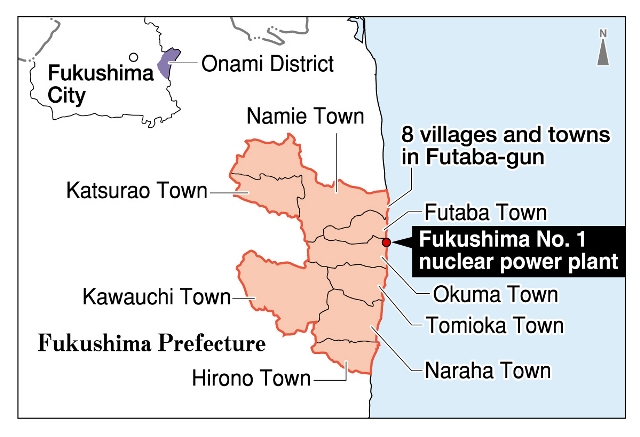

Survey of eight municipalities near nuclear power plant

Residents first seek “vision for the future”

What do the residents of Fukushima who have been compelled to live as evacuees want? Fukushima University conducted a survey targeting all of the households in the eight municipalities in Futaba-gun in the vicinity of the nuclear power plant. The results showed that residents are most interested in the formulation of a rebuilding plan and industrial development. They want projects that will allow them to experience rebuilding firsthand.

A total of 13,463 households, 47.8 percent of the total, responded to the survey.

When asked what issues their area faced in terms of rebuilding, at 48.5 percent the greatest number of respondents said “formulation of a plan for the recovery of the entire Futaba district.” (Multiple answers were allowed.) With regard to specific requests, 44.5 percent said “industrial development such as securing jobs for young people” while 32.2 percent selected “ample medical facilities and facilities for the elderly.”

But when residents were asked about their intention to return to their former homes, 26.9 percent said they would not go back. Young people in particular seemed to have little desire to return to their hometowns. By age group, 52.3 percent of those 34 and younger said they did not want to go back.

As for the reasons for their lack of a desire to return home, 83.1 percent said “decontamination will be difficult.” (Multiple answers were allowed.) A total of 65.7 percent said they “could not trust the government’s declaration that the area was safe.”

Of those who said they wanted to return home, 37.4 percent said they would be willing to wait one or two years. When those who said they wanted to return within one year are included the figure rises to 50.2 percent. Only 14.6 percent said they would be willing to wait indefinitely.

Survey Methodology

With the cooperation of the eight municipalities in the area (Namie, Tomioka, Okuma, Naraha, Futaba, Hirono, Kawauchi, and Katsurao), in September the Fukushima University Disaster Recovery Research Institute sent surveys to the 28,184 households on the official list of evacuees and asked a representative of each household to complete the survey. The findings were announced in November.

Analysis of findings

An interview with Fuminori Tamba, associate professor at Fukushima University

Fuminori Tamba, an associate professor of social welfare at Fukushima University’s Disaster Recovery Research Institute, conducted a survey targeting all of the households in the eight municipalities that comprise Futaba-gun. The Chugoku Shimbun asked him about his findings.

A total of 26.9 percent of the respondents said they did not intend to go back to the areas where they formerly resided. How do you view this result?

If people had evacuated on account of the earthquake and tsunami only, many more would have expressed a desire to return home. When asked if they had an attachment to their hometowns, 60 to 70 percent in every age group said they did. Even among those 34 or younger, who constituted the majority of those who said they did not intend to return to their homes, about 60 percent said they had an attachment to their hometowns. The problem is the radioactive contamination. In the space for comments one person wrote, “Rebuilding will be impossible if young people can’t live here.” The mayors of the eight municipalities seemed to be shocked by the results of the survey.

More than 80 percent of the respondents said they believed that the decontamination being planned and implemented by the central government and local municipalities will be difficult. How do you regard that?

At the root of this is distrust of the central government, which was affected by its failure to disclose information just after the disaster. Decontamination will not only cost a tremendous amount of money, it will also take a long time. In response to the survey, 74.1 percent said they would be unwilling to continue living as evacuees for more than three years. From the comments, I learned that quite a few people want the central government to buy their land. The central government should conduct a survey on the residents’ feelings as soon as possible and set out detailed assistance measures.

I’ve heard you are the grandson of a survivor of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. Are there assistance measures that can make use of Hiroshima’s experiences?

As a result of the accident at the nuclear power plant more than 60,000 people evacuated to areas outside Fukushima Prefecture. Late-onset disorders resulting from their exposure to radiation may appear anytime from a few years to a few decades from now. The evacuees need to be tracked into the future and provided with support. I sympathize with the notion that “atomic bomb survivors are atomic bomb survivors wherever they are.” The government must create a system like the Atomic Bomb Survivor's Certificate that will allow people to get health care anywhere in Japan.

Fuminori Tamba

Born in Ama, Aichi Prefecture, in 1973. Received a master’s degree from Nihon Fukushi University. Assumed his current post in 2004 after serving as a counselor at a facility for mentally handicapped children and as a full-time instructor at Himeji Hinomoto College. Also serves as a member of the Reconstruction Advisory Panel in Namie.

(Originally published on December 6, 2011)