Fukushima and Hiroshima: Reconstruction and Reality, Part 7 [3]

Dec. 15, 2011

Article 3: Restructuring the medical system

by Kei Kinugawa, Staff Writer

Number of doctors drops by half, hampering examinations

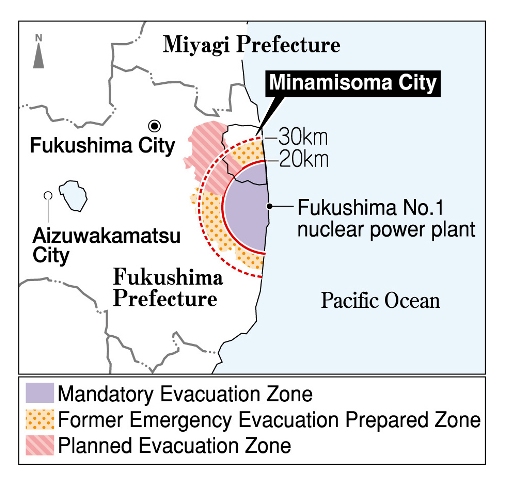

Takahiro Oto, 45, a company employee, lived in the city of Minamisoma, in Fukushima Prefecture, prior to the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant. In late November, Mr. Oto returned to his hometown for just one day. Since the accident, Mr. Oto and his family have continued to live the life of evacuees in the city of Aizuwakamatsu, about 95 kilometers to the west of the crippled power station. He returned to Minamisoma so that his five-year-old daughter could undergo a check of her thyroid gland.

How long will he and his family continue to live as evacuees? Mr. Oto has a single benchmark for his decision. “We won’t go back to live in Minamisoma until the day the doctors who also fled the city have returned,” he said. In other words, this will be the day when medical personnel, who have expertise in radiation, will judge the situation safe for themselves on a personal level. At the same time, once the doctors have returned to the city, reliable medical care will then be available for Mr. Oto and his family.

Nurses and clinical technicians left the area as well

Before the accident at the nuclear plant, eight hospitals were in operation in Minamisoma. Among these eight, two lie within the boundary of the Mandatory Evacuation Zone, within a radius of 20 kilometers from the plant, and have been deemed off-limits. The remaining six hospitals continue to function, but the number of full-time physicians in the city is now just 28, slightly more than half of the total of 54 prior to the accident. The number of nurses and clinical technicians plunged sharply, too.

One of the challenges involving the reconstruction of the affected areas is the restructuring of the medical system. When Fukushima University conducted a survey which targeted all households in eight municipalities near the power plant, about 30 percent of the respondents cited “improving social welfare and medical facilities” as an important issue.

Why did the doctors leave Minamisoma? There are several factors behind this development.

In the wake of the accident, the central government ordered hospitals lying within a radius of 30 kilometers from the plant to evacuate their inpatients. As a result, some of the doctors staffing these hospitals became redundant and assumed new posts at hospitals outside the city.

The doctors also harbor a fear of radiation. The number of full-time physicians working at the Minamisoma City General Hospital has dwindled to seven, half the number that were serving the hospital before the accident. Yukio Kanazawa, 58, director of the hospital said, “Many of the doctors who left the hospital have small children. I can understand their feelings about wanting to keep a distance from the nuclear power plant.” The number of available beds for inpatients has also fallen from 230, before the earthquake, to 120 today. When winter takes hold and the number of patients with serious illnesses increases, the hospital will be unable to accept a greater influx of inpatients.

In early October, the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare launched a “support center” aimed at securing doctors and nurses for Minamisoma. In cooperation with Fukushima Medical University, located in the city of Fukushima, the center will work to place a stable supply of doctors in area hospitals after probing the human resource needs of these facilities.

Establishing an organization to share medical information is vital

Hokuto Hoshi, 47, executive director of the Fukushima Prefectural Medical Association, has given thought to this problem. “The question now,” he said, “is how to respond to the concerns held by the people of Fukushima with regard to managing their health and receiving cancer screenings, rather than constructing new facilities for advanced medical care. It’s vital to establish an organization where doctors can share information on health care in the region, as was the case in Hiroshima after the atomic bombing when the Regional Health Care Council of Hiroshima Prefecture was established.”

Yet hope is out there. Among medical students, it may be true that some are avoiding job openings in Fukushima Prefecture, but others are entertaining the idea of serving in the area and contributing to the medical care of local residents.

Students at Fukushima Medical University have been assisting people with the task of filling in medical interview forms which help estimate their level of radiation exposure. Shota Endo, 23, a fourth-year student at the university took part in a volunteer activity which involved preparing meals at an evacuation center. “Before, I only thought about leaving Fukushima,” he said. “But now I’m thinking I’d like to stay here and help the local people.”

(Originally published on December 8, 2011)