Akira Yoshiyama, 81, Naka Ward, Hiroshima

May 16, 2014

Heading home, he was unable to respond to calls for help

“There was nothing a 12-year-old boy could do. But even now, my heart still aches.”

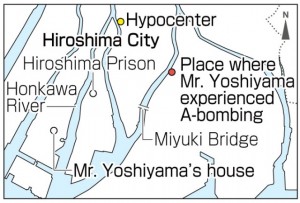

On the morning of August 6, 1945, Akira Yoshiyama, now 81, a first-year student at Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Commercial School (today’s Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Commercial High School), was on his way to school when the atomic bomb was dropped. He was in Minami-machi (part of present-day Minami Ward), 1.8 kilometers from the hypocenter, when the blast occurred. Afterward, as he headed for home in Eba-cho (part of present-day Naka Ward), he observed the horrific conditions caused by a single atomic bomb. He said, “Only eyewitnesses can really understand what it was like. Still, I want to talk about it, about the war and the atomic bombing, because, in war, human beings aren’t treated as human beings.”

On the day of the bombing, Mr. Yoshiyama, who was 12 at the time, was running late for school so he jumped onto a streetcar. His school was originally located in Eba, but the building had been commandeered by the Japanese military, and so the school was moved to Minami-machi, where another school had once stood. When the streetcar reached the stop at Hijiyamabashi, in front of the school, he saw that teachers and students were standing in lines on the schoolyard. In a hurry, he leaped from the streetcar and, at that moment, he was enveloped in the A-bomb’s bright flash.

He apparently lost consciousness for a while, and when he came to, it was dark around him. He hadn’t suffered burns from the blast, but a red welt rose on his head. His school cap, with its school badge, was gone. “If I lose my cap, I’ll have to write a letter of apology,” he thought, and searched for it frantically. “At that time, teachers often hit students, and I was scared of them,” he explained.

He finally gave up searching for the hat, and went on to the school, where he found that all the fences had been destroyed. Some students had fallen to the ground and others were just standing there. One of his friends said that he couldn’t see, so Mr. Yoshiyama took off his gaiters from his legs and wound them around his friend’s waist. Pulling on the gaiters, he led the friend to a military hospital in Ujina-cho (now part of Minami Ward). Even the hallways of the hospital were jammed with the injured.

He then headed home. Passing by Miyuki Bridge, he saw a big dead horse by the side of the bridge. Many of the people he saw had blistered skin and walked with their arms stretched out like ghosts, their tattered clothes dangling down from their waists like grass skirts. He saw flames over at the head office of the Hiroshima Electric Railways in Sendamachi (part of present-day Naka Ward).

Hurrying home, he ignored the calls for help from people trapped under fallen homes. Looking back, he said, “There was nothing a 12-year-old boy could do. But even now, my heart still aches.”

After crossing the southern grounds of Hiroshima Prison in Yoshijima-cho (part of Naka Ward), he came upon a boat. Because he grew up in a fishing village, he was able to row the boat and ferry some wounded people across the Honkawa River.

Among the injured was a soldier whose lower leg was missing, exposing bare bone. Mr. Yoshiyama was surprised to see that when the boat arrived at Funairi, the soldier disembarked and walked away faster than he expected. It was an incredible sight, he said.

He finally arrived home around 3 p.m. His mother, Tatsu, 43, was thrilled that he had survived. Feeling deep relief at the sight of his mother, Mr. Yoshiyama then recalls the stench of burnt human flesh in his nostrils. At this point, he fell unconscious.

Mr. Yoshiyama’s father, Yasuichi, 47, and elder sister, Tomiko, 18, also survived and the family fled to his maternal grandparents’ house in Fuchu-cho. When the war ended not long after, “I was angry that Japan had lost and bitter at the United States.” However, when the students were no longer struck by teachers and older schoolmates, he felt that “democracy” had been born in Japan.

After the war, Mr. Yoshiyama worked at various companies, including for an electrician, before joining Toyo Kogyo, which became today’s Mazda Motor Corporation. He married in 1957, and now has two children and five grandchildren.

“There mustn’t be war and nuclear weapons, but it isn’t easy to eliminate them,” he said. “Therefore, I want young people to know right from wrong, and value other human beings.” (Junji Akechi, Staff Writer)

Teenagers’ Impressions

I want to do what I can, however small

I was shocked when Mr. Yoshiyama said, “Even if young people make an effort, nuclear weapons and nuclear power plants won’t be abolished,” and his words made me think about this deeply. It’s true that this is very tough, and it might not be possible to abolish them all. However, in order to reduce their numbers, even one by one, I want to do what I can to convey the importance of peace to the people around me, including continuing my work as a junior writer. (Hiromi Ueoka, 13)

Loss is like an earthquake in your life

Thinking about people who have suffered as a result of the accident at the nuclear power plant in Fukushima, Mr. Yoshiyama said that it’s a pity they can’t return to the hometowns where they were born. It’s the same when people lose their homes to war and earthquakes. We have to remember the fact that there are people who have experienced the loss of not only their homes, but the anchor to their lives, and we should do what we can to prevent something like this from happening again. (Shino Taniguchi, 15)

I was surprised at the harsh life during the war

I was surprised at the harshness of school life during the war. For example, if a student broke a rule, the whole class was punished, and students who were just a year older took it for granted that they could strike their younger peers. It’s hard for me to understand. People’s values are greatly influenced by a nation’s policies. This is why I feel concerned that the shift to the right by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s government could change the pacifism of the Japanese people. (Yuka Ichimura, 17)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

Because of the chaotic conditions in the aftermath of the atomic bombing, Mr. Yoshiyama is unsure about certain aspects of his experience. For example, he was apparently exposed to the blast at a streetcar stop, but why was he on the bank of a river, closer to the hypocenter, when he came to? He isn’t sure why he didn’t suffer burns or what sort of injuries his friend received.

Mr. Yoshiyama was 12 years old at the time, the same age as today’s first-year junior high school students. He was quite young, so it’s natural that he wouldn’t clearly remember the details. When I interviewed him, I felt the “distance” of what happened 69 years ago.

As Mr. Yoshiyama didn’t want to be reminded of that time, for many years he avoided an annual memorial service for the victims of his school. Around ten years ago, though, he finally started to attend the ceremony. Then recently, when he read an article in the newspaper, about an A-bomb survivor who shares his story, he thought, “My experience could be useful, too.” Perhaps because his experience had become more “distant,” Mr. Yoshiyama was finally ready to speak about his own past.

This led me to believe that there are other survivors, still concealing their memories, who are actually waiting for an opportunity to begin speaking out. (Junji Akechi)

(Originally published on April 15, 2014)

“There was nothing a 12-year-old boy could do. But even now, my heart still aches.”

On the morning of August 6, 1945, Akira Yoshiyama, now 81, a first-year student at Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Commercial School (today’s Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Commercial High School), was on his way to school when the atomic bomb was dropped. He was in Minami-machi (part of present-day Minami Ward), 1.8 kilometers from the hypocenter, when the blast occurred. Afterward, as he headed for home in Eba-cho (part of present-day Naka Ward), he observed the horrific conditions caused by a single atomic bomb. He said, “Only eyewitnesses can really understand what it was like. Still, I want to talk about it, about the war and the atomic bombing, because, in war, human beings aren’t treated as human beings.”

On the day of the bombing, Mr. Yoshiyama, who was 12 at the time, was running late for school so he jumped onto a streetcar. His school was originally located in Eba, but the building had been commandeered by the Japanese military, and so the school was moved to Minami-machi, where another school had once stood. When the streetcar reached the stop at Hijiyamabashi, in front of the school, he saw that teachers and students were standing in lines on the schoolyard. In a hurry, he leaped from the streetcar and, at that moment, he was enveloped in the A-bomb’s bright flash.

He apparently lost consciousness for a while, and when he came to, it was dark around him. He hadn’t suffered burns from the blast, but a red welt rose on his head. His school cap, with its school badge, was gone. “If I lose my cap, I’ll have to write a letter of apology,” he thought, and searched for it frantically. “At that time, teachers often hit students, and I was scared of them,” he explained.

He finally gave up searching for the hat, and went on to the school, where he found that all the fences had been destroyed. Some students had fallen to the ground and others were just standing there. One of his friends said that he couldn’t see, so Mr. Yoshiyama took off his gaiters from his legs and wound them around his friend’s waist. Pulling on the gaiters, he led the friend to a military hospital in Ujina-cho (now part of Minami Ward). Even the hallways of the hospital were jammed with the injured.

He then headed home. Passing by Miyuki Bridge, he saw a big dead horse by the side of the bridge. Many of the people he saw had blistered skin and walked with their arms stretched out like ghosts, their tattered clothes dangling down from their waists like grass skirts. He saw flames over at the head office of the Hiroshima Electric Railways in Sendamachi (part of present-day Naka Ward).

Hurrying home, he ignored the calls for help from people trapped under fallen homes. Looking back, he said, “There was nothing a 12-year-old boy could do. But even now, my heart still aches.”

After crossing the southern grounds of Hiroshima Prison in Yoshijima-cho (part of Naka Ward), he came upon a boat. Because he grew up in a fishing village, he was able to row the boat and ferry some wounded people across the Honkawa River.

Among the injured was a soldier whose lower leg was missing, exposing bare bone. Mr. Yoshiyama was surprised to see that when the boat arrived at Funairi, the soldier disembarked and walked away faster than he expected. It was an incredible sight, he said.

He finally arrived home around 3 p.m. His mother, Tatsu, 43, was thrilled that he had survived. Feeling deep relief at the sight of his mother, Mr. Yoshiyama then recalls the stench of burnt human flesh in his nostrils. At this point, he fell unconscious.

Mr. Yoshiyama’s father, Yasuichi, 47, and elder sister, Tomiko, 18, also survived and the family fled to his maternal grandparents’ house in Fuchu-cho. When the war ended not long after, “I was angry that Japan had lost and bitter at the United States.” However, when the students were no longer struck by teachers and older schoolmates, he felt that “democracy” had been born in Japan.

After the war, Mr. Yoshiyama worked at various companies, including for an electrician, before joining Toyo Kogyo, which became today’s Mazda Motor Corporation. He married in 1957, and now has two children and five grandchildren.

“There mustn’t be war and nuclear weapons, but it isn’t easy to eliminate them,” he said. “Therefore, I want young people to know right from wrong, and value other human beings.” (Junji Akechi, Staff Writer)

Teenagers’ Impressions

I want to do what I can, however small

I was shocked when Mr. Yoshiyama said, “Even if young people make an effort, nuclear weapons and nuclear power plants won’t be abolished,” and his words made me think about this deeply. It’s true that this is very tough, and it might not be possible to abolish them all. However, in order to reduce their numbers, even one by one, I want to do what I can to convey the importance of peace to the people around me, including continuing my work as a junior writer. (Hiromi Ueoka, 13)

Loss is like an earthquake in your life

Thinking about people who have suffered as a result of the accident at the nuclear power plant in Fukushima, Mr. Yoshiyama said that it’s a pity they can’t return to the hometowns where they were born. It’s the same when people lose their homes to war and earthquakes. We have to remember the fact that there are people who have experienced the loss of not only their homes, but the anchor to their lives, and we should do what we can to prevent something like this from happening again. (Shino Taniguchi, 15)

I was surprised at the harsh life during the war

I was surprised at the harshness of school life during the war. For example, if a student broke a rule, the whole class was punished, and students who were just a year older took it for granted that they could strike their younger peers. It’s hard for me to understand. People’s values are greatly influenced by a nation’s policies. This is why I feel concerned that the shift to the right by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s government could change the pacifism of the Japanese people. (Yuka Ichimura, 17)

Staff Writer’s Notebook

Because of the chaotic conditions in the aftermath of the atomic bombing, Mr. Yoshiyama is unsure about certain aspects of his experience. For example, he was apparently exposed to the blast at a streetcar stop, but why was he on the bank of a river, closer to the hypocenter, when he came to? He isn’t sure why he didn’t suffer burns or what sort of injuries his friend received.

Mr. Yoshiyama was 12 years old at the time, the same age as today’s first-year junior high school students. He was quite young, so it’s natural that he wouldn’t clearly remember the details. When I interviewed him, I felt the “distance” of what happened 69 years ago.

As Mr. Yoshiyama didn’t want to be reminded of that time, for many years he avoided an annual memorial service for the victims of his school. Around ten years ago, though, he finally started to attend the ceremony. Then recently, when he read an article in the newspaper, about an A-bomb survivor who shares his story, he thought, “My experience could be useful, too.” Perhaps because his experience had become more “distant,” Mr. Yoshiyama was finally ready to speak about his own past.

This led me to believe that there are other survivors, still concealing their memories, who are actually waiting for an opportunity to begin speaking out. (Junji Akechi)

(Originally published on April 15, 2014)