Akinori Okada, 86, Asakita Ward, Hiroshima

Nov. 17, 2014

Images of atomic bombing haunt dreams after sharing experience

by Masanori Wada, Staff Writer

“Radiation is scary because its effects are invisible. After the atomic bombing, I faced discrimination because people thought I was faking illness,” said Akinori Okada, 86. Mr. Okada was 17 when he was exposed to the atomic bomb. For several years after the war, he suffered fatigue and weariness from the effects of the bomb’s radiation, the so-called “A-bomb lazy disease.” Though he wanted to work, he wasn’t strong enough, and others looked upon him coldly, as an idler.

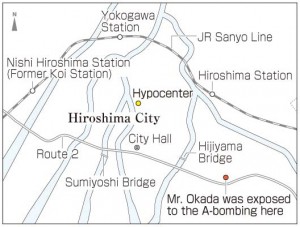

Mr. Okada was a fourth-year student at Sotoku Junior High School when he experienced the atomic bombing. On August 6, 1945, he was assigned to work as a mobilized student at the former Hiroshima Army Ordnance Supply Depot (where Hiroshima University’s Kasumi Campus is located today) in the Kasumi area (now Minami Ward), located 2.7 kilometers from the hypocenter. He and his friends were resting in a brick building before the morning meeting. Their job that day was to pack rifles and ammunition in crates.

Hearing the roar of airplanes, he stepped outside and saw B-29 bombers in the sky. He remembers how their duralumin bodies were shining so beautifully. As he was going back into the building, he was enveloped by a bluish white light and lost consciousness. “I didn’t hear the ‘don’ of ‘pikadon.’ I only remember ‘pika,’” he said, using the compound word made up of onomatopoeic expressions for the flash (“pika”) and the explosion (“don”) of the atomic bomb.

When he came to, he found that he had been blown off his feet by the blast, to a corner of the room, and a pencil was stuck in his right palm. He saw people walking into the depot to ask soldiers for help, their skin dangling from their hands like pieces of string. He knew that something awful had happened. His teacher told him and his friends to stand by at home, so he and three classmates headed toward Hiroshima Station.

They passed through the Danbara area (now Minami Ward), but they could not venture the Matoba-cho district (also Minami Ward) because of fires. So they decided to cross the Hijiyama and Sumiyoshi bridges to go to Yokogawa Station (now Nishi Ward).

At Sumiyoshi Bridge, he heard his name called in a weak voice. It was one of his classmates who had been mobilized to help dismantle homes to create a fire lane in the Kakomachi district (now Naka Ward) in case of air raids. His body was pierced with a three-by-three centimeter timber from the abdomen to the back. Mr. Okada and his friends carried him on a wooden door, which they found on the riverside, to Koi Station (now Nishi Ward), where the classmate was loaded onto a military truck to transport the injured.

Mr. Okada thinks that his own life was saved because he helped his friend. If he had gone through the center of Hiroshima to reach Yokogawa Station, he could have been exposed to a massive amount of radiation. Instead of crossing the heart of the city, he walked back to Obayashi (now Asakita Ward) where he sought temporary refuge. He then finally arrived home at 8 o’clock that evening.

The following morning he had a high fever, of unknown origin, which lasted for more than two weeks. By the time the fever broke, the war had come to an end. After the war, he completed his schooling though he was unable to attend classes. Because of the “A-bomb lazy disease,” he was in poor physical condition for a long while.

A major turning point came more than one year after the bombing. Mr. Okada was the fifth son of ten children. His parents had died before the war, and they lived with their aunt Tamie (then 23), who took care of the children, in the countryside to avoid air raids. The brothers and sisters decided to go back to Kinzagai in central Hiroshima where they used to live. There, they began running a tobacco shop. The area was a bustling place after the war, and their business took off. At the same time, he regained his health.

Discrimination against A-bomb survivors affected his marriage prospects. His girlfriend’s mother would not accept him solely because he was an A-bomb survivor. Later, he married Sachiko. (Sachiko died in 2004 at the age of 71.) Neither Mr. Okada nor Sachiko, who was exposed to residual radiation when she entered Hiroshima shortly after the atomic bombing, told the other that they were a survivor. “I couldn’t tell her because I was afraid of prejudice,” said Mr. Okada, who learned that Sachiko was also a survivor when they had their first daughter. Though they were worried about the genetic effects of radiation on their daughter, thankfully, their two daughters have not shown any worrisome signs.

Mr. Okada said, “Images of the atomic bombing still haunt my dreams after I tell my account.” The terrible devastation wrought by the atomic bomb and the discrimination he experienced after the war are unwanted memories that he had long concealed even from his family. What changed his mind was the nuclear accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant, run by the Tokyo Electric Power Company, which was triggered by the great earthquake and tsunami in March 2011. “Because I personally know the horrific effects of radiation, I have to share my experience with younger generations,” he thought. He plans to turn his account into a picture-card show [kamishibai, a traditional form of Japanese storytelling] so that children can easily grasp his experience.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Never repeat the same mistake

When I heard about his classmate whose body had been pierced with a stick, I realized again how terrible the atomic bombing was. War hurts innocent people. Our generation must learn about the atomic bombing and convey its horror to the next generation. We must never repeat the same mistake. (Terumi Okada, second-year junior high school student)

We must hand down his desire

Mr. Okada had to pretend that he didn’t notice when high school girls suffering burns pleaded for water. He might have regrets about this since they still appear in his dreams after he tells his A-bomb account. He continues to talk about his experience, though, because of his strong wish that war should not be fought again. We must hand down his desire to future generations. (Mirai Yamashita, first-year high school student)

Living in present-day Japan is a blessing

When Mr. Okada said, “War is no good, I want peace,” I realized that those of us living in present-day Japan are blessed. But many people are still suffering from war or conflict in other parts of the world. It’s now etched in my mind that we must convey the horror of war so that this precious peace will be maintained in the future and can spread around the world. (Satoko Hirata, second-year high school student)

(Originally published on November 3, 2014)