100th anniversary of A-Bomb Dome: Silent plea

Apr. 13, 2015

by Michiko Tanaka, Staff Writer

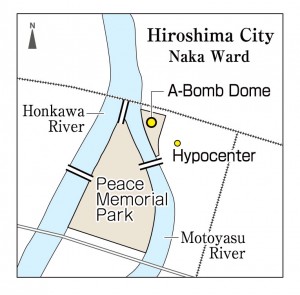

The Atomic Bomb Dome will turn 100 on April 5. Originally called the Hiroshima Commercial Exhibition Hall, the building in the city’s Naka Ward is now a UNESCO World Heritage site. It continues to bear silent witness to the horrors of the use of nuclear weapons and to sound a warning to humanity. Before the war, the building’s elegant lines endeared it to local citizens. After the war, the debate on whether or not to preserve it inspired controversy. This article looks back on the vicissitudes of the building’s 100-year history.

●Prewar: industrial promotion role diminishes

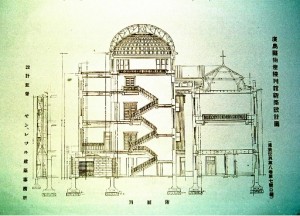

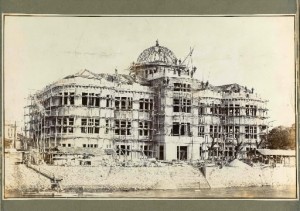

In a headline in its April 3, 1915 edition following completion of the Hiroshima Commercial Exhibition Hall, the Chugoku Shimbun described the hall as the “big, white building.” The building had three floors of brick and a five-story center portion that featured a dome. The exterior was covered with stone and mortar. The European-style design was the work of Czech architect Jan Letzel (1880-1925).

The prefecture pushed for construction of the building in an effort to enhance the quality of local products and develop new sales outlets for them. The dedication ceremony was held on April 5, and a product fair was held for the next 40 days. Products primarily from Hiroshima Prefecture were featured, including tatami mats from the Bingo region and traditional handicrafts from Miyajima. Lectures and art exhibitions were subsequently held in the building, which became popular as the site of cultural events.

The building’s name was subsequently changed to the Hiroshima Prefectural Products Exhibition Hall and later to the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall. As the war expanded, the building was used for other purposes. Starting in 1941, public offices and “control associations” began occupying offices there. The final public event held in the building was an exhibition of works depicting scenes from the “holy war” in December 1943. It featured paintings of scenes from the war by famous artists such as Tsuguharu Fujita and Saburo Miyamoto.

The collection of the Peace Memorial Museum includes a picture postcard that was issued for the exhibition. It was donated to the museum in 2005 by Hiroshima resident Chieko Suetomo, 86, who bought it when she went to see the exhibition. At the time, she was a third-year student at the junior and senior high school affiliated with the Hiroshima Girls’ Normal School. “I was busy with volunteer labor in those days and neglected my studies,” she said. “That was common at the time, and everyone believed we were fighting a ‘holy war.’ Those were sad times.”

When the atomic bomb was dropped on the morning of August 6, 1945, Ms. Suetomo was working as a mobilized student in Koiue-machi (now part of Nishi Ward). “We must never experience times like that again,” she said and hopes that the picture postcard will remind people of that.

●A-bombing: number of victims remains unknown

The atomic bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima by the United States at 8:15 a.m. on August 6, 1945, exploded about 600 meters above the ground about 160 meters southeast of the Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall. “By rights, I should have died there too,” said Hiroshima resident Kimie Mihara, 89, lowering her gaze. “I feel guilty when I think of my coworkers who died.” She worked in the accounting department of the Chugoku-Shikoku Public Works Office of the Home Ministry, which was located on the building’s first floor.

On the day of the atomic bombing Ms. Mihara was late for work, which started at 8 a.m., for the first time. “For some reason, I didn’t feel like going,” she said. The day before she had been assigned to work on the dismantling of buildings to create fire breaks near her workplace, and she was tired. She reluctantly left her home in Atago-cho (now part of Higashi Ward) and went to Hiroshima Station (in what is now Minami Ward). While waiting for a streetcar she saw a brilliant flash and was blown into the station. Her arms, legs and neck were badly burned, and she was bedridden for three months. Her father, Kyoichi Oga, 42, a civilian employee of the army, was at an army facility in Moto-machi (now part of Naka Ward). His remains have never been found.

Ms. Mihara first saw her nearly unrecognizable workplace from the window of a streetcar at the end of the year. “I couldn’t stop crying,” she said. “I put my hands together in prayer and said, ‘I’m sorry.’” Even now, whenever she visits the Atomic Bomb Dome, she observes a moment of silence before the monument on which the names of the Home Ministry employees are inscribed. “The A-Bomb Dome is like a grave. I would like it to be cared for always,” Ms. Mihara said.

The damage to the Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall was described in the Record of the Hiroshima Atomic Bombing published by the city: “All 30 of the people inside the hall were killed instantly.” The exact number of those who died in the building, however, remains unknown.

●Postwar: after debate, decision made to preserve structure

Although nearly directly below the bomb blast, the Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall somehow escaped total destruction and remained standing amid the burned-out ruins of the city. In 1966, 21 years after the A-bombing, it was decided to permanently preserve the building. Many citizens said that the structure’s bare bricks and steel framework brought back memories of the terrible atomic bombing, and the city was thrown into a commotion by the ongoing debate over whether to preserve the building or dismantle it.

In October 1949 the city surveyed 500 survivors of the atomic bombing, asking whether they wanted the remains of the industrial hall to be preserved. The results of the survey were carried in the February 11, 1950 edition of the Chugoku Shimbun, which reported that 62 percent favored preservation while 35 percent wanted the remains to be cleared away. Shinso Hamai, then mayor of Hiroshima, initially advocated dismantling the building, and wrote an opinion piece for the paper in which he expressed that opinion.

One factor that led people to support preservation of the A-bomb dome was the diary of Hiroko Kajiyama. She was 1 year old and in Hiratsuka-cho (now part of Naka Ward) at the time of the atomic bombing. On August 6, 1959, she wrote in her diary: “Only the pitiful Industrial Promotion Hall will forever tell the world of the dreadful atomic bombing.” Ms. Kajiyama died of acute leukemia in April of the following year at the age of 16.

In August of that year school students belonging to a peace organization called the Hiroshima Paper Crane Club, who knew about Ms. Kajiyama’s diary, launched petition and fund-raising drives seeking the preservation of the Atomic Bomb Dome. Other peace groups got involved in their movement, and it gradually spread. In 1965 the city conducted a study of the A-Bomb Dome’s strength and concluded that it could be preserved. In July 1966 the city council passed a resolution seeking preservation of the dome.

In November the city launched a drive to raise funds to help with the cost of the work on the structure. Mayor Hamai stood on street corners in Tokyo as well as Hiroshima soliciting donations. The effort resonated with people from all walks of life. In 1967 the city issued a commemorative publication that listed the names of cultural figures and people in the performing arts including Nobel Prize winner Hideki Yukawa, writer Yasunari Kawabata, actor Takahiro Tamura, U.S. journalist Norman Cousins and Indian jurist Radhabinod Pal.

The move to preserve the A-Bomb Dome gained the support of ordinary people as well. There are more than 10,000 names on a list of donors in the Hiroshima Municipal Archives. The donation from one elementary school student was accompanied by a letter that said: “I believe that the A-Bomb Dome, which conveys the horror of war, must not be torn down.” At the end of nine months the city had raised 66.19 million yen, far exceeding the target of 40 million yen.

●Future: carrying hopes for nuclear abolition

The city’s preservation work on the A-Bomb Dome began in April 1967. Hiroshima resident Shojiro Futakuchi, 94, a former employee of the Hiroshima branch of Shimizu Corporation, a leading general contractor, worked as a foreman on the project. “It was scary,” he recalled. “We were supposed to be preserving the building but it seemed we were going to destroy it.”

Bricks were scattered about the grounds of the A-Bomb Dome, which were enclosed by a wire fence. Mr. Futakuchi recalled that if you pushed against the walls of the building, they wobbled. There were large fissures in the walls, and sparrows had built nests in some places. The work involved stabilizing a damaged building in its damaged condition – an unprecedented task.

Walls that seemed likely to collapse were stabilized between steel braces, and then resin was injected as an adhesive. It took 19 tons of resin to do the job. Materials that were standard overseas could not be used because of the high cost of importing them, so parts made by local manufacturers were used instead after testing their strength. In order to finish the work by the anniversary of the atomic bombing, the job had to be finished in three months. Tents were put up over the scaffolding so that the work could continue on rainy days. Workers gave up their weekends to work on the job and managed to finish on August 5.

Mr. Futakuchi also directed the preservation work conducted by the city in 1989. He said that as an engineer he believes the building will last a long time provided that it is properly maintained. In 1996 the Atomic Bomb Dome became the first war-related site in Japan to be designated a UNESCO World Heritage site.

The A-Bomb Dome is inspected every three years to determine how much deterioration has occurred. At the time of the most recent inspection in late March of this year, Mr. Futakuchi was interviewed in front of the A-Bomb Dome by members of the “PC Broadcasting Club” at Ushita Junior High School in Higashi Ward. The students filmed the interview with Mr. Futakuchi for a program they are producing in conjunction with the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombing. “I would like you to tell people about the significance of the A-Bomb Dome in your own words,” Mr. Futakuchi said to the students. “Tell them it must be preserved forever.”

After the interview, Yuki Yamamoto, 14, a third-year student at the junior high school, expressed surprise at Mr. Futakuchi’s remarks. “I just took the dome for granted, but it has memories for a lot of people,” she said. “I’d like to produce a video that will get people thinking about how to perceive the dome and how to tell others about it.” She said that she hopes that one hundred years from now it will stand as a symbol of the world peace and of humankind’s elimination of nuclear weapons.

History of the A-bomb Dome

Dec. 1910

Hiroshima Prefecture decides to build a commercial exhibition hall

April 5, 1914

Hiroshima Commercial Exhibition Hall completed

Jan. 1921

Name changed to Hiroshima Prefectural Products Exhibition Hall

Nov. 1933

Name changed to Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall

Dec. 7, 1941

Japan attacks Pearl Harbor

Aug. 6, 1945

Atomic bomb is dropped almost directly over the Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, which suffers major damage and is burned out

Aug. 15, 1945

War ends

Oct. 1949

City of Hiroshima surveys 500 atomic bomb survivors as to whether or not to preserve the former Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall; 62 percent (428 respondents) favor preservation while 35 percent favor clearing away the ruins

Nov. 1953

Prefecture transfers A-bomb Dome to city

Aug. 1960

Hiroshima Paper Crane Club launches petition and fund-raising drives to preserve the Atomic Bomb Dome

Dec. 1964

Eleven peace organizations, including both of the Hiroshima Council Against A- and H-bombs groups and the prefectural division of the National Council for Peace and Against Nuclear Weapons, ask Hiroshima Mayor Shinso Hamai to preserve the building

July 1965

City spends 1 million yen on study of structure’s strength; the study is contracted out to Professor Shigeo Sato of Hiroshima University’s Faculty of Engineering, who says the building can be preserved if it is reinforced

July 1966

City council unanimously approves resolution calling for preservation of Atomic Bomb Dome

Nov. 1966

City launches drive to raise funds to preserve building; target of 40 million yen is exceeded in March 1967 and Mayor Hamai announces end of fund-raising drive; by the end of July, 66.2 million yen has been raised

April 1967

City undertakes first preservation work; completed in August

July 1987

City establishes committee to study technology needed to preserve the A-Bomb Dome

March 1988

It is disclosed in a meeting of the House of Representatives Budget Subcommittee that the Foreign Ministry will study the A-Bomb Dome for designation as a heritage site under the Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage

March 1989

City plans second preservation project, launches fund-raising drive, which ends in December after raising 370 million yen

Oct. 1989

Work begins on second preservation project, which is completed in March 1990

Sept. 1992

City council unanimously adopts resolution calling on the central government to recommend addition of the A-Bomb Dome to the world’s “Cultural Heritage” list under the terms of the Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage

June 1993

At the urging of the Hiroshima local of the Japanese Trade Union Confederation, 13 organizations in Hiroshima Prefecture form a group to promote designation of the A-Bomb Dome as a World Heritage site

June 1995

A-Bomb Dome designated a national historic site

Dec. 1996

A-Bomb Dome listed as World Heritage site

March 2001

Geiyo Earthquake

Oct. 2002

City embarks on third preservation project, which is completed in March 2003

Aug. 2007

First meeting of the seismic reinforcement subcommittee of the city’s Advisory Committee on Preservation Techniques for the A-bomb Dome

June 2013

City begins sampling material from the walls of the A-Bomb Dome for an in-depth study of its earthquake resistance

Jan. 2014

City announces it will carry out first seismic retrofit; work scheduled to begin after August 6, 2015

(Originally published on April 4, 2015)

The Atomic Bomb Dome will turn 100 on April 5. Originally called the Hiroshima Commercial Exhibition Hall, the building in the city’s Naka Ward is now a UNESCO World Heritage site. It continues to bear silent witness to the horrors of the use of nuclear weapons and to sound a warning to humanity. Before the war, the building’s elegant lines endeared it to local citizens. After the war, the debate on whether or not to preserve it inspired controversy. This article looks back on the vicissitudes of the building’s 100-year history.

●Prewar: industrial promotion role diminishes

In a headline in its April 3, 1915 edition following completion of the Hiroshima Commercial Exhibition Hall, the Chugoku Shimbun described the hall as the “big, white building.” The building had three floors of brick and a five-story center portion that featured a dome. The exterior was covered with stone and mortar. The European-style design was the work of Czech architect Jan Letzel (1880-1925).

The prefecture pushed for construction of the building in an effort to enhance the quality of local products and develop new sales outlets for them. The dedication ceremony was held on April 5, and a product fair was held for the next 40 days. Products primarily from Hiroshima Prefecture were featured, including tatami mats from the Bingo region and traditional handicrafts from Miyajima. Lectures and art exhibitions were subsequently held in the building, which became popular as the site of cultural events.

The building’s name was subsequently changed to the Hiroshima Prefectural Products Exhibition Hall and later to the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall. As the war expanded, the building was used for other purposes. Starting in 1941, public offices and “control associations” began occupying offices there. The final public event held in the building was an exhibition of works depicting scenes from the “holy war” in December 1943. It featured paintings of scenes from the war by famous artists such as Tsuguharu Fujita and Saburo Miyamoto.

The collection of the Peace Memorial Museum includes a picture postcard that was issued for the exhibition. It was donated to the museum in 2005 by Hiroshima resident Chieko Suetomo, 86, who bought it when she went to see the exhibition. At the time, she was a third-year student at the junior and senior high school affiliated with the Hiroshima Girls’ Normal School. “I was busy with volunteer labor in those days and neglected my studies,” she said. “That was common at the time, and everyone believed we were fighting a ‘holy war.’ Those were sad times.”

When the atomic bomb was dropped on the morning of August 6, 1945, Ms. Suetomo was working as a mobilized student in Koiue-machi (now part of Nishi Ward). “We must never experience times like that again,” she said and hopes that the picture postcard will remind people of that.

●A-bombing: number of victims remains unknown

The atomic bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima by the United States at 8:15 a.m. on August 6, 1945, exploded about 600 meters above the ground about 160 meters southeast of the Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall. “By rights, I should have died there too,” said Hiroshima resident Kimie Mihara, 89, lowering her gaze. “I feel guilty when I think of my coworkers who died.” She worked in the accounting department of the Chugoku-Shikoku Public Works Office of the Home Ministry, which was located on the building’s first floor.

On the day of the atomic bombing Ms. Mihara was late for work, which started at 8 a.m., for the first time. “For some reason, I didn’t feel like going,” she said. The day before she had been assigned to work on the dismantling of buildings to create fire breaks near her workplace, and she was tired. She reluctantly left her home in Atago-cho (now part of Higashi Ward) and went to Hiroshima Station (in what is now Minami Ward). While waiting for a streetcar she saw a brilliant flash and was blown into the station. Her arms, legs and neck were badly burned, and she was bedridden for three months. Her father, Kyoichi Oga, 42, a civilian employee of the army, was at an army facility in Moto-machi (now part of Naka Ward). His remains have never been found.

Ms. Mihara first saw her nearly unrecognizable workplace from the window of a streetcar at the end of the year. “I couldn’t stop crying,” she said. “I put my hands together in prayer and said, ‘I’m sorry.’” Even now, whenever she visits the Atomic Bomb Dome, she observes a moment of silence before the monument on which the names of the Home Ministry employees are inscribed. “The A-Bomb Dome is like a grave. I would like it to be cared for always,” Ms. Mihara said.

The damage to the Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall was described in the Record of the Hiroshima Atomic Bombing published by the city: “All 30 of the people inside the hall were killed instantly.” The exact number of those who died in the building, however, remains unknown.

●Postwar: after debate, decision made to preserve structure

Although nearly directly below the bomb blast, the Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall somehow escaped total destruction and remained standing amid the burned-out ruins of the city. In 1966, 21 years after the A-bombing, it was decided to permanently preserve the building. Many citizens said that the structure’s bare bricks and steel framework brought back memories of the terrible atomic bombing, and the city was thrown into a commotion by the ongoing debate over whether to preserve the building or dismantle it.

In October 1949 the city surveyed 500 survivors of the atomic bombing, asking whether they wanted the remains of the industrial hall to be preserved. The results of the survey were carried in the February 11, 1950 edition of the Chugoku Shimbun, which reported that 62 percent favored preservation while 35 percent wanted the remains to be cleared away. Shinso Hamai, then mayor of Hiroshima, initially advocated dismantling the building, and wrote an opinion piece for the paper in which he expressed that opinion.

One factor that led people to support preservation of the A-bomb dome was the diary of Hiroko Kajiyama. She was 1 year old and in Hiratsuka-cho (now part of Naka Ward) at the time of the atomic bombing. On August 6, 1959, she wrote in her diary: “Only the pitiful Industrial Promotion Hall will forever tell the world of the dreadful atomic bombing.” Ms. Kajiyama died of acute leukemia in April of the following year at the age of 16.

In August of that year school students belonging to a peace organization called the Hiroshima Paper Crane Club, who knew about Ms. Kajiyama’s diary, launched petition and fund-raising drives seeking the preservation of the Atomic Bomb Dome. Other peace groups got involved in their movement, and it gradually spread. In 1965 the city conducted a study of the A-Bomb Dome’s strength and concluded that it could be preserved. In July 1966 the city council passed a resolution seeking preservation of the dome.

In November the city launched a drive to raise funds to help with the cost of the work on the structure. Mayor Hamai stood on street corners in Tokyo as well as Hiroshima soliciting donations. The effort resonated with people from all walks of life. In 1967 the city issued a commemorative publication that listed the names of cultural figures and people in the performing arts including Nobel Prize winner Hideki Yukawa, writer Yasunari Kawabata, actor Takahiro Tamura, U.S. journalist Norman Cousins and Indian jurist Radhabinod Pal.

The move to preserve the A-Bomb Dome gained the support of ordinary people as well. There are more than 10,000 names on a list of donors in the Hiroshima Municipal Archives. The donation from one elementary school student was accompanied by a letter that said: “I believe that the A-Bomb Dome, which conveys the horror of war, must not be torn down.” At the end of nine months the city had raised 66.19 million yen, far exceeding the target of 40 million yen.

●Future: carrying hopes for nuclear abolition

The city’s preservation work on the A-Bomb Dome began in April 1967. Hiroshima resident Shojiro Futakuchi, 94, a former employee of the Hiroshima branch of Shimizu Corporation, a leading general contractor, worked as a foreman on the project. “It was scary,” he recalled. “We were supposed to be preserving the building but it seemed we were going to destroy it.”

Bricks were scattered about the grounds of the A-Bomb Dome, which were enclosed by a wire fence. Mr. Futakuchi recalled that if you pushed against the walls of the building, they wobbled. There were large fissures in the walls, and sparrows had built nests in some places. The work involved stabilizing a damaged building in its damaged condition – an unprecedented task.

Walls that seemed likely to collapse were stabilized between steel braces, and then resin was injected as an adhesive. It took 19 tons of resin to do the job. Materials that were standard overseas could not be used because of the high cost of importing them, so parts made by local manufacturers were used instead after testing their strength. In order to finish the work by the anniversary of the atomic bombing, the job had to be finished in three months. Tents were put up over the scaffolding so that the work could continue on rainy days. Workers gave up their weekends to work on the job and managed to finish on August 5.

Mr. Futakuchi also directed the preservation work conducted by the city in 1989. He said that as an engineer he believes the building will last a long time provided that it is properly maintained. In 1996 the Atomic Bomb Dome became the first war-related site in Japan to be designated a UNESCO World Heritage site.

The A-Bomb Dome is inspected every three years to determine how much deterioration has occurred. At the time of the most recent inspection in late March of this year, Mr. Futakuchi was interviewed in front of the A-Bomb Dome by members of the “PC Broadcasting Club” at Ushita Junior High School in Higashi Ward. The students filmed the interview with Mr. Futakuchi for a program they are producing in conjunction with the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombing. “I would like you to tell people about the significance of the A-Bomb Dome in your own words,” Mr. Futakuchi said to the students. “Tell them it must be preserved forever.”

After the interview, Yuki Yamamoto, 14, a third-year student at the junior high school, expressed surprise at Mr. Futakuchi’s remarks. “I just took the dome for granted, but it has memories for a lot of people,” she said. “I’d like to produce a video that will get people thinking about how to perceive the dome and how to tell others about it.” She said that she hopes that one hundred years from now it will stand as a symbol of the world peace and of humankind’s elimination of nuclear weapons.

History of the A-bomb Dome

Dec. 1910

Hiroshima Prefecture decides to build a commercial exhibition hall

April 5, 1914

Hiroshima Commercial Exhibition Hall completed

Jan. 1921

Name changed to Hiroshima Prefectural Products Exhibition Hall

Nov. 1933

Name changed to Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall

Dec. 7, 1941

Japan attacks Pearl Harbor

Aug. 6, 1945

Atomic bomb is dropped almost directly over the Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, which suffers major damage and is burned out

Aug. 15, 1945

War ends

Oct. 1949

City of Hiroshima surveys 500 atomic bomb survivors as to whether or not to preserve the former Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall; 62 percent (428 respondents) favor preservation while 35 percent favor clearing away the ruins

Nov. 1953

Prefecture transfers A-bomb Dome to city

Aug. 1960

Hiroshima Paper Crane Club launches petition and fund-raising drives to preserve the Atomic Bomb Dome

Dec. 1964

Eleven peace organizations, including both of the Hiroshima Council Against A- and H-bombs groups and the prefectural division of the National Council for Peace and Against Nuclear Weapons, ask Hiroshima Mayor Shinso Hamai to preserve the building

July 1965

City spends 1 million yen on study of structure’s strength; the study is contracted out to Professor Shigeo Sato of Hiroshima University’s Faculty of Engineering, who says the building can be preserved if it is reinforced

July 1966

City council unanimously approves resolution calling for preservation of Atomic Bomb Dome

Nov. 1966

City launches drive to raise funds to preserve building; target of 40 million yen is exceeded in March 1967 and Mayor Hamai announces end of fund-raising drive; by the end of July, 66.2 million yen has been raised

April 1967

City undertakes first preservation work; completed in August

July 1987

City establishes committee to study technology needed to preserve the A-Bomb Dome

March 1988

It is disclosed in a meeting of the House of Representatives Budget Subcommittee that the Foreign Ministry will study the A-Bomb Dome for designation as a heritage site under the Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage

March 1989

City plans second preservation project, launches fund-raising drive, which ends in December after raising 370 million yen

Oct. 1989

Work begins on second preservation project, which is completed in March 1990

Sept. 1992

City council unanimously adopts resolution calling on the central government to recommend addition of the A-Bomb Dome to the world’s “Cultural Heritage” list under the terms of the Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage

June 1993

At the urging of the Hiroshima local of the Japanese Trade Union Confederation, 13 organizations in Hiroshima Prefecture form a group to promote designation of the A-Bomb Dome as a World Heritage site

June 1995

A-Bomb Dome designated a national historic site

Dec. 1996

A-Bomb Dome listed as World Heritage site

March 2001

Geiyo Earthquake

Oct. 2002

City embarks on third preservation project, which is completed in March 2003

Aug. 2007

First meeting of the seismic reinforcement subcommittee of the city’s Advisory Committee on Preservation Techniques for the A-bomb Dome

June 2013

City begins sampling material from the walls of the A-Bomb Dome for an in-depth study of its earthquake resistance

Jan. 2014

City announces it will carry out first seismic retrofit; work scheduled to begin after August 6, 2015

(Originally published on April 4, 2015)