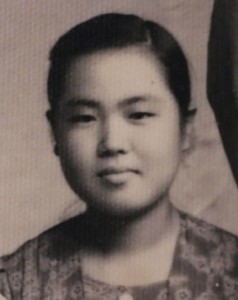

Yoshiko Yanagawa, 85, Hatsukaichi City, Hiroshima

May 26, 2015

by Tsuyoshi Osabe, Staff Writer

Yoshiko Yanagawa (nee Nakamura) survived the atomic bombing thanks to the help of many people. She still recalls the day more than 20 years ago when one of her grandchildren, then an elementary school student, said to her, “Grandma, why did adults go to war? Why didn’t they say it was wrong?” This made her ask herself whether she had a responsibility to tell others about her experiences. Since 1992 she has been recounting her A-bombing experiences, primarily to schoolchildren on field trips.

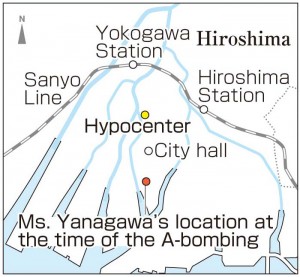

At the time of the atomic bombing, Ms. Yanagawa was 16 years old and a fourth-year student at the junior and senior high school affiliated with the Hiroshima Girls’ Normal School. On August 6, 1945, she was at the school, which was located in Senda-machi (now part of Naka Ward), about 1.7 km from the hypocenter. She heard the sound of the propellers of a bomber and then saw a flash and heard a roar that made her think the sun had exploded. The school building fell apart, and she lost consciousness.

When she came to, all around her was completely still. She was trapped under the school building. She had been taught to be willing to sacrifice her life for her country and believed she was prepared to die. But at that time she felt strongly that she did not want to die.

She called out to her teacher and wriggled toward the light that shone through the debris. Her teacher, who had heard her cry, pulled her out, and she found herself on the roof of the collapsed two-story school building. Both she and her teacher were covered with blood, and a piece of wood had pierced her teacher’s back.

After she emerged, she realized that the fingertips on her right hand were nearly touching the ground. Her collarbone was broken and her shoulder was at the level of her stomach. There were shards of glass in her skin from the left side of her face to the back of her neck.

She got some first aid treatment and then began walking to Yokogawa (now part of Nishi Ward), where her home was. She thought the bomb had fallen in Senda-machi where her school was located, so she was astounded to discover that the entire city was a sea of flames.

In the vicinity of Kamiya-cho (now part of Naka Ward), near the hypocenter, she saw several charred dead bodies still standing. Their eyes were open and their tongues were hanging out. A soldier who was still alive begged her for water, but she could do nothing for him and went on her way. “I still feel guilty about that,” she said, choking up. “It’s an unbearable emotional scar.”

A friend put her up for the night, and the next morning she was reunited with her brother, who was three years older, in Yokogawa. They headed for Jigozen (now part of the city of Hatsukaichi), where their father’s birthplace was. The family had decided that they would meet there in the event of an emergency. Perhaps because she was relieved at having found her brother, Ms. Yanagawa’s strength gave out, and her brother carried her most of the way.

After they arrived in Jigozen, a relative used scissors to cut Ms. Yanagawa’s uniform, which was stuck to her body. The uniform was in tatters and covered in blood. The relative also pulled out the shards of glass that had pierced her body. For the next two or three days Ms. Yanagawa slept as if she were dead.

Her mother and younger brother also made it to Jigozen, but her father, who had been summoned by the military and gone out early on the morning of August 6, was never found.

Two years after the war ended, she married. Her husband, Isamu, was in the army at the time of the atomic bombing. Ms. Yanagawa heard from a relative that Isamu had transported and burned the dead bodies that had been stacked up in Hiroshima. Though he supported his wife’s efforts to recount her A-bombing experiences, he never once spoke of his own. He died seven years ago at the age of 84.

“He was by nature a quiet man. It must have been such a terrible experience that he couldn’t bring himself to talk about it,” Ms. Yanagawa said. “Many people have died, keeping their memories to themselves. Drawing on the feelings of those people, I want to tell the younger generation that I would like them to bring about a peaceful world.”

Receiving the baton of peace

Ms. Yanagawa said that a student on a field trip to whom she had talked about her experiences said to her, “I have received the baton.” Her expression then made an impression on me because I could sense her desire to have her memories passed on to the next generation. The horrors of the atomic bombing must never be repeated. I have also received from Ms. Yanagawa the baton to continue to tell of peace. (Miki Meguro, 12)

Grasp feelings and disseminate them

During our interview with Ms. Yanagawa, she smiled most of the time, but her expression occasionally hardened. I sensed that it was painful for her to recall her experiences. But she told us she would like us to imagine the situation at the time of the A-bombing and think about what we can do to ensure that it never happens again. I would like to grasp the feelings of the atomic bomb survivors and tell others about them. (Shiho Fujii, 13)

Surprised at strength to survive

Ms. Yanagawa was 16 at the time of the atomic bombing, the same age I am now. She described the scene as “not of this world” and “like hell.” I can’t imagine whether I could have survived if I had been in the same circumstances. Her experiences were so horrible that she said she could not feel anything. Ms. Yanagawa overcame that and has survived to this day. I was surprised at her strength. (Marina Misaki, 16)

(Originally published on May 25, 2015)

Inspired by grandchild to tell of her experiences; lingering guilt, emotional scar

Yoshiko Yanagawa (nee Nakamura) survived the atomic bombing thanks to the help of many people. She still recalls the day more than 20 years ago when one of her grandchildren, then an elementary school student, said to her, “Grandma, why did adults go to war? Why didn’t they say it was wrong?” This made her ask herself whether she had a responsibility to tell others about her experiences. Since 1992 she has been recounting her A-bombing experiences, primarily to schoolchildren on field trips.

At the time of the atomic bombing, Ms. Yanagawa was 16 years old and a fourth-year student at the junior and senior high school affiliated with the Hiroshima Girls’ Normal School. On August 6, 1945, she was at the school, which was located in Senda-machi (now part of Naka Ward), about 1.7 km from the hypocenter. She heard the sound of the propellers of a bomber and then saw a flash and heard a roar that made her think the sun had exploded. The school building fell apart, and she lost consciousness.

When she came to, all around her was completely still. She was trapped under the school building. She had been taught to be willing to sacrifice her life for her country and believed she was prepared to die. But at that time she felt strongly that she did not want to die.

She called out to her teacher and wriggled toward the light that shone through the debris. Her teacher, who had heard her cry, pulled her out, and she found herself on the roof of the collapsed two-story school building. Both she and her teacher were covered with blood, and a piece of wood had pierced her teacher’s back.

After she emerged, she realized that the fingertips on her right hand were nearly touching the ground. Her collarbone was broken and her shoulder was at the level of her stomach. There were shards of glass in her skin from the left side of her face to the back of her neck.

She got some first aid treatment and then began walking to Yokogawa (now part of Nishi Ward), where her home was. She thought the bomb had fallen in Senda-machi where her school was located, so she was astounded to discover that the entire city was a sea of flames.

In the vicinity of Kamiya-cho (now part of Naka Ward), near the hypocenter, she saw several charred dead bodies still standing. Their eyes were open and their tongues were hanging out. A soldier who was still alive begged her for water, but she could do nothing for him and went on her way. “I still feel guilty about that,” she said, choking up. “It’s an unbearable emotional scar.”

A friend put her up for the night, and the next morning she was reunited with her brother, who was three years older, in Yokogawa. They headed for Jigozen (now part of the city of Hatsukaichi), where their father’s birthplace was. The family had decided that they would meet there in the event of an emergency. Perhaps because she was relieved at having found her brother, Ms. Yanagawa’s strength gave out, and her brother carried her most of the way.

After they arrived in Jigozen, a relative used scissors to cut Ms. Yanagawa’s uniform, which was stuck to her body. The uniform was in tatters and covered in blood. The relative also pulled out the shards of glass that had pierced her body. For the next two or three days Ms. Yanagawa slept as if she were dead.

Her mother and younger brother also made it to Jigozen, but her father, who had been summoned by the military and gone out early on the morning of August 6, was never found.

Two years after the war ended, she married. Her husband, Isamu, was in the army at the time of the atomic bombing. Ms. Yanagawa heard from a relative that Isamu had transported and burned the dead bodies that had been stacked up in Hiroshima. Though he supported his wife’s efforts to recount her A-bombing experiences, he never once spoke of his own. He died seven years ago at the age of 84.

“He was by nature a quiet man. It must have been such a terrible experience that he couldn’t bring himself to talk about it,” Ms. Yanagawa said. “Many people have died, keeping their memories to themselves. Drawing on the feelings of those people, I want to tell the younger generation that I would like them to bring about a peaceful world.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

Receiving the baton of peace

Ms. Yanagawa said that a student on a field trip to whom she had talked about her experiences said to her, “I have received the baton.” Her expression then made an impression on me because I could sense her desire to have her memories passed on to the next generation. The horrors of the atomic bombing must never be repeated. I have also received from Ms. Yanagawa the baton to continue to tell of peace. (Miki Meguro, 12)

Grasp feelings and disseminate them

During our interview with Ms. Yanagawa, she smiled most of the time, but her expression occasionally hardened. I sensed that it was painful for her to recall her experiences. But she told us she would like us to imagine the situation at the time of the A-bombing and think about what we can do to ensure that it never happens again. I would like to grasp the feelings of the atomic bomb survivors and tell others about them. (Shiho Fujii, 13)

Surprised at strength to survive

Ms. Yanagawa was 16 at the time of the atomic bombing, the same age I am now. She described the scene as “not of this world” and “like hell.” I can’t imagine whether I could have survived if I had been in the same circumstances. Her experiences were so horrible that she said she could not feel anything. Ms. Yanagawa overcame that and has survived to this day. I was surprised at her strength. (Marina Misaki, 16)

(Originally published on May 25, 2015)