Takeo Sugiyama, 83, Asa Minami Ward, Hiroshima

Mar. 10, 2014

Unable to find sister in burned-out city

Searched worksite, bodies seemed like mere “things”

by Sakiko Masuda, Staff Writer

The day after the atomic bombing, Takeo Sugiyama, 83, searched for his younger sister, Yoshiko, who had been working on the demolition of buildings to create fire breaks in an area near the hypocenter. As he walked the area he saw people with their internal organs spilling out of their wounded bellies and clusters of bodies on top of each other in the river. He was unable to find his sister amid the burned-out ruins of the city.

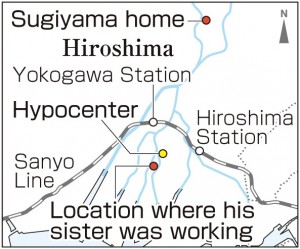

Mr. Sugiyama was 14 and a third-year student at Sotoku Junior High School. Because he had lung trouble, he could not participate in the demolition of buildings in Kako-machi (now part of Naka Ward), near the hypocenter, and was resting at home in Furuichi-cho (now part of Asa Minami Ward), about 7 km north of the hypocenter.

On the day of the atomic bombing, Mr. Sugiyama’s mother, who was tending the fields, called to him, “A B-29 is flying over!” Just as he went outside, suddenly there was a hot, bluish-white flash of light. “It’s hot!” he cried. Then he saw a ball of fire in the southern sky. With a load roar the blast wave came through, destroying the roof of their house and blowing off the storm shutters and sliding doors.

His three younger brothers were also at home, but none of them was hurt. The mushroom cloud rose in the skies above downtown Hiroshima.

After a while, injured people began to arrive one after another. Mr. Sugiyama wondered if his sister was all right and hoped she had managed to flee the destruction. Twelve-year-old Yoshiko was a first-year student at Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ High School (now Funairi High School). She had set out early that morning to work on the demolition of buildings in Kobiki-cho (now part of Naka Ward), near the school.

On the morning of August 7, Mr. Sugiyama and other relatives went to look for Yoshiko. He said he would never forget the terrible sight of the area where his sister had been working, which is now part of Peace Memorial Park. He saw the body of a woman who appeared to be a teacher who had died trying to save her students. Another body was pinned under a utility pole. “Bodies just looked like ‘things’ to me,” Mr. Sugiyama said. “I didn’t feel sorry that they had died.”

He went home and told his mother about what he had seen and that he had been unable to find his sister. She listened quietly and then began weeping loudly. Mr. Sugiyama recovered his senses for the first time and dissolved into tears.

After the war Mr. Sugiyama found out that his classmates who had been working on the demolition of buildings also died in the A-bombing. His mother continued to mourn the loss of her daughter. Mr. Sugiyama began to feel bad about what had happened. “I felt guilty about having escaped death,” he said. “I wished I had died.”

But his mother said to him, “Because I have you, I can somehow go on living.” He began to feel he wanted to live his sister’s share of life as well and ease his mother’s grief. He studied hard, graduated from Hiroshima University and became a junior high school teacher, the career he had wanted to pursue.

He married in 1959, and has two children and five grandchildren. In 1991 he retired from his final post as principal of Gion Higashi Junior High School (Asa Minami Ward).

He tells children, “The peace we enjoy today was built on the sacrifices of many people. I want you to think about how conflicts can be resolved and how we can build peace. I would like you to build peace, starting with yourself, and then widen the circle.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

Frightfulness of inability to feel

I was shocked when Mr. Sugiyama said that as he walked around the hypocenter area looking for his sister dead bodies seemed like mere “things” to him. Ordinarily people would feel sorry or afraid, but he couldn’t think about anything. I realized once again the frightfulness of the A-bombing, which not only robbed many people of their lives but also robbed those who survived of their ability to feel. (Shiho Fujii, 12 years old)

Peace begins with me

Mr. Sugiyama decided to live his sister’s life as well and said he wanted us to value life more. He said he felt it was unfortunate that so many people commit suicide or readily kill other people these days. I will try harder to be honest and broad-minded and to build peace starting with myself. (Yuka Iguchi, 18 years old)

Hiroshima Insight

Peace Memorial Park

Design proposals solicited from all over Japan

Peace Memorial Park in Hiroshima’s Naka Ward encompasses a triangular area bordered by the Honkawa and Motoyasu rivers and Peace Boulevard as well as the vicinity of the A-bomb Dome. Completed in 1954, the park covers 12.21 hectares. Before being completely destroyed in the atomic bombing on August 6, 1945, the area was a bustling shopping district.

The city came up with the idea of building a park there shortly after the end of the war, and in April 1949 design proposals for a park that would serve as a “permanent bastion for world peace” were solicited from throughout Japan. In August of that year the design submitted by a group led by Kenzo Tange (1913-2005), then an assistant professor at Tokyo University, was selected from among 145 proposals.

The group’s plan was characterized by its alignment of the A-bomb Dome, the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims and the Peace Memorial Museum. The dome was registered as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1996, and the park was designated a National Place of Scenic Beauty in 2007.

There are numerous monuments in the park, including the Children’s Peace Monument inspired by Sadako Sasaki, a young girl who died of leukemia, as well as survivors of the A-bombing, including the Rest House and some Chinese parasol trees.

(Originally published on March 10, 2014)