Hiroshima, 70 Years After the Atomic Bombing: Rebirth of the City, Part 1 [2]

Jul. 24, 2015

Part 1 [2]: Young police officers plunge into rescue operations, lead survivors to safety

by Masanori Wada, Staff Writer

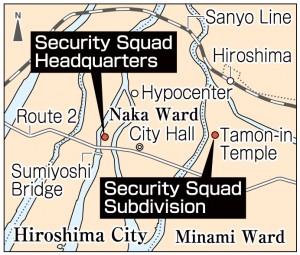

It was the first assignment given to Tokumi Shintani, then an 18-year-old police officer. Now an 88-year-old resident of Fukuyama, Mr. Shintani belonged to the security squad of the Hiroshima Prefectural Police Department. When the atomic bomb exploded, he was at Tamon-in Temple in the Danbara area (now part of Minami Ward), where his subdivision was stationed. As he was not seriously injured, he was ordered by his superior to find out what happened to the headquarters of the security squad in Kako-machi (now part of Naka Ward). Four hours after the bombing, he headed for the city center, moving against the tide of people who were running to make their escape.

Military draft leaves police understaffed

Because Japanese men were being drafted into the military, the police department was short of staff and had to employ younger men. In June 1945, Mr. Shintani became the youngest policeman--he was just 17 at the time. In July, he was assigned to the security squad, which was responsible for maintaining security in the event of an air raid.

In the bombing’s aftermath, Mr. Shintani put on a helmet and stuck a whistle in his pocket. He encountered flames everywhere. Unable to withstand the fiery winds, he jumped into a river and soaked his uniform in the water. A female student suffering from burns called for his help, but he had no medicine or bandages. He could only tell her to wait for the army’s rescue team to come.

About 30 minutes later, he found that the headquarters of the squad had been completely destroyed. Near Sumiyoshi Bridge, he saw the president of the police school, who was seriously injured and was using a saber for a cane. He told Mr. Shintani to help with the rescue operations.

Mr. Shintani guided survivors to safety, leading them to the southern part of the city. He also carried people who were seriously injured to a bridge or river bank so they could be easily found by rescue workers on military trucks. One survivor asked him for water, and he brought some river water in a can and helped the person drink. But the water ran right out through a slit in his throat. It was an unimaginable nightmare, Mr. Shintani said.

According to the Record of the A-bomb Disaster and other documents, about 500 officers were engaged in law enforcement operations in the aftermath of the bombing. By August 20, two weeks after the attack, the police had recovered the bodies of 17,865 victims.

After the war, the security squad was disbanded along with the pre-war police organization, symbolized by the Special Political Police. Mr. Shintani was retrained at the police school to serve as a member of a democratic police system.

He then worked at the police box within the jurisdiction of the Hiroshima East Police Station. He remembers a shoeshine boy who came crying that his customer did not pay, and his colleague gave the boy some money. Many police officers were forced to leave the force because of health problems, but he continued his career with the prefectural police department. “Because I witnessed the horrible conditions of the city after the bombing, I wanted to see, as a police officer, how Hiroshima would be reconstructed,” he said.

The “biggest crimes”

Seiso Shiramasa, 87 years old and a resident of Asakita Ward, was also engaged in rescue operations near Sumiyoshi Bridge on that day. Mr. Shiramasa and Mr. Shintani joined the police department in the same year. For a week after the attack, as he slept among the debris, Mr. Shiramasa undertook such tasks as confirming whether residents were alive and carrying bodies of the dead. After the war, he was retrained and became a detective. Lauded for his service, he mainly handled crime involving theft. “Many of these crimes involved kimonos that were stolen and then sold on the black market,” he explained. “We didn’t have guns or handcuffs in those days, so we chased after the thieves holding only our police baton.”

Both former police officers hesitate to talk about their hard work, saying that they were just doing their duty. But as they recalled the event that transpired 70 years ago, the same sentiment was unexpectedly and forcefully expressed: “The atomic bombings were the biggest crimes ever committed by human beings.”

(Originally published on July 15, 2015)