Hiroshima, 70 Years After the Atomic Bombing: Rebirth of the City, Part 1 [3]

Jul. 27, 2015

Part 1 [3]: Workers labored to give light to the city amid A-bomb ruins

by Koji Higuchi, Staff Writer

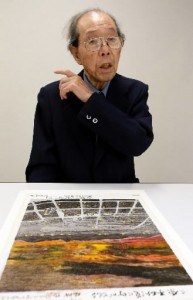

There is an oil painting of the atomic bombing which depicts a night view from the top of Hijiyama Hill in Minami Ward, looking toward the west. The painting shows dotted lights coming from buildings around the collapsed Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall (now the Atomic Bomb Dome in Naka Ward). The painter, who titled it “Lights Appear in the Atomic Desert,” captured the ruins of Hiroshima at 8 p.m. on September 10, 1945, about one month after the atomic bombing.

At 8:15 a.m. on August 6, 1945, the United States dropped the atomic bomb, which instantly decimated the infrastructure of the city of Hiroshima. At the time, Tetsuro Mukai, 94, a resident of Higashi Ward, was on the fourth floor, working in the engineering division of the Chugoku Haiden headquarters (now the Chugoku Electric Power Company in Naka Ward), about 700 meters from the hypocenter. The blast blew him, and his desk, five meters across the room. He said, “I took off my jacket, put it over my head, and fled the building. I yelled to a female worker who was screaming on the second floor to jump. A colleague and I caught her.”

Electricity returned to the city at end of August

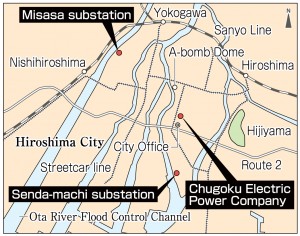

Mr. Mukai helped extinguish the flames at the Senda-machi power station (now the Senda-machi substation), which supplied electricity to the city center. He spent that night in an air-raid shelter in Kokutaiji-machi (now part of Naka Ward), and returned to the headquarters of the power company at 10 a.m. the following day. Approximately 100 of his coworkers, or one-third of the employees working in the building, were killed in the bombing. Mr. Mukai helped cremate their bodies. “Looking back now, it wouldn't have been difficult to escape the situation,” he said. “But I stayed because I was driven by a sense of duty to see electricity restored to the city.”

Working alongside colleagues, he then repaired the broken switchboard at the Misasa substation (in present-day Nishi Ward,) which led to resuming its operations at the end of August 1945. More than 80 percent of the wooden utility poles within one kilometer of the hypocenter were destroyed by fire. Following the instructions given by the late Yasuo Sanada, the former vice president of the Chugoku Electric Power Company, who was the manager of the planning department at the time of the atomic bombing and directed efforts to restore the electricity supply, Mr. Mukai and his colleagues raised the leaning wooden poles, lifted the electric wires from the ground, and stretched these wires between the poles with the help of others from the cities of Miyoshi and Kure. Although Mr. Mukai was actually a design engineer, he was engaged in this restoration work, too, explaining, “We didn’t have enough people, anyway.”

Until August 24, when his symptoms of radiation sickness, such as hair loss, grew more acute, Mr. Mukai went out each day and worked in the ruins. After he was able to take a sick leave, he recuperated at his house in Miyoshi, his hometown. His white blood cell count had fallen dramatically, but he managed to survive, thanks to 100 vitamin injections sent by Mr. Sanada. Mr. Sanada, he said, was the person who saved his life. In a book titled The History of Showa for Business Leaders in Hiroshima, which was published in 1988, Mr. Sanada said that he labored to restore the city’s power supply over a period of six months without a single day off. That November, electricity was completely restored for Hiroshima’s remaining houses and buildings.

Oil painting made 30 years later

After the war, the A-bombed facilities for distributing electric power to the city, including the Senda-machi power station, were restored one by one. These facilities were then able to meet the growing demand for electricity. Ten years into the postwar period, the capacity of the Chugoku Electric Power Company reached twice the supply of prewar conditions. This greater power supply could also support the rapid economic growth which came afterward.

The person who made the oil painting also helped rebuild Hiroshima’s infrastructure. Gisaku Tanaka (who died in 2000 at the age of 98), led efforts to lay cables underground around Hiroshima station (now part of Minami Ward) as a signal engineer for Japan National Railways.

On the day of the atomic bombing, Mr. Tanaka was returning to work after the weekend off. He was riding a train from his home in Shimonoseki, Yamaguchi Prefecture to Hiroshima, where he encountered the aftermath of the A-bomb attack. Thirty years later, he painted the scene from Hijiyama Hill, which he saw when he visited his aunt who lived in the area in the month after the bombing when electricity had been largely restored in the city center. Yoriko Tanaka, 69, his daughter-in-law, lived with Mr. Tanaka before he passed away. She recalled how he described the scene with a smile and the words, “There was light in the darkness.”

The restoration of the electric power supply brought hope to the people of Hiroshima in reconstructing the city as a whole. Seventy years after the bombing, Akimasa Ueda, 49, a manager at the Chugoku Electric Power Company, said firmly, “We are very proud of the spirit shown by our predecessors, who were able to restore electricity to the city despite the devastating conditions. We are doing our best to carry on their sense of mission, always placing top priority on the lives of citizens.”

(Originally published on July 16, 2015)