Hiroshima, 70 Years After the Atomic Bombing: Rebirth of the City, Part 1 [4]

Jul. 27, 2015

Part 1 [4]: Workers take pride in uninterrupted water supply

by Masanori Wada, Staff Writer

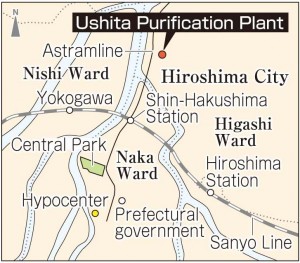

“Continuously, day and night.” A passage from the Analects of Confucius, meaning “a constant flow of river water,” is displayed near the entrance of a red brick building that was exposed to the atomic bomb. The building is a former water pump house (now the Museum of Waterworks) at the Ushita Purification Plant in Higashi Ward, Hiroshima. Even on August 6, 1945, the day of the atomic bombing nearly 70 years ago, Hiroshima’s “water of life” never went dry. “This is an important place, providing proof that there was no interruption in Hiroshima’s water supply,” Yoshihide Ishida said with pride. Mr. Ishida, 86, is a former city official of the Water Supply Division of the waterworks department (currently, the Waterworks Bureau).

The former pump house is located approximately 2.8 kilometers from the hypocenter. The roof and walls were blown down by the bomb’s massive blast and all seven motorized pumps which pumped water to the city’s only distribution reservoir stopped functioning. However, because the reservoir was almost full of water at the time, an interruption to the city’s water supply was averted. It was predicted, though, that this water supply would eventually go dry.

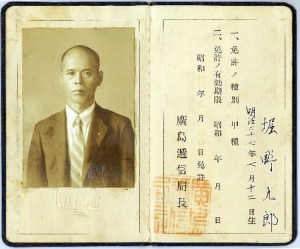

In these conditions, Kuro Horino, who was a 51-year-old engineer in the Water Supply Division, quickly rushed to the pump house and turned on a heavy oil-operated backup pump equipped with an internal-combustion engine. Though suffering from burns to his body, he managed to repair the pumps temporarily and, at 2 o’clock in the afternoon, was able to restart the water supply to the distribution reservoir. His prompt response saved the city from experiencing a water outage.

Struggle to restore the water supply

Still, the waterworks department continued their struggle to restore the water supply long after the war ended. This is because water pipes lay broken in various parts of the burnt ruins and water leaked from the taps of homes that had been destroyed. Mr. Ishida, who began working for the city in 1947, said, “It was like pouring water into a strainer.” These were dire conditions in which most of the water supply was leaking out.

Restoring the water pipes took steady efforts. Mr. Ishida, who was a new employee back then, loaded tools onto a large, two-wheeled cart and a bicycle, then went around the wrecked city with more experienced workers. Soaked with sweat, they crushed leaking water pipes with hammers and stopped them up with cone-shaped wooden plugs. During this time, Mr. Ishida heard the story of Mr. Horino’s valiant efforts on August 6 from the other workers.

In those days, shacks built side by side began appearing in the so-called “atomic bomb slums” of the Motomachi district (near today’s Central Park) along the Honkawa River. This district had no access to the city’s water supply. Mr. Ishida installed a shared tap for every five households and set water flowing to the area. “The residents were so grateful,” he recalled. “But I was worried whether the district would ever be reconstructed.”

Reconstruction efforts in Hiroshima reached their peak around 1951. Still, it was about 10 years after the atomic bombing that Mr. Ishida felt the impact of this work in the city. Looking back, he said, “Every family was poor, but they were eventually able to get enough water, if nothing else.”

Story becomes picture-story show

The decrepit pump house became a waterworks museum in 1985, and in 1993 it was registered by the City of Hiroshima as an A-bombed building. Currently, the Museum of Waterworks is closed for anti-earthquake reinforcement work until March 2016. After reopening, the daily record of the pump operations at the time of the atomic bombing, and afterward, will be displayed. The story of Mr. Horino’s efforts that day has been used at elementary schools as educational material, and the city’s Waterworks Bureau made a picture-story show entitled “Inochi no Mizu” (“The Water of Life”) based on Mr. Horino’s achievement.

After the war, Mr. Horino contributed his account to the Hiroshima Shiyakusho Genbaku-shi (Record of the Atomic Bombing by the Hiroshima City Office), published by the city in 1966. In his account, Mr. Horino wrote: “When I saw people drinking from a fire hydrant under those terrible conditions after the atomic bombing, I really recognized the preciousness of water and the significance and responsibility of my work.”

Mr. Ishida said, “If I had been in the same situation as Mr. Horino, I, as well as everyone else on our staff, would have responded in the same way.” The pride taken in the uninterrupted water supply since 1898, when water first started to flow in the city, has been preserved by subsequent generations.

(Originally published on July 18, 2015)